‘From dark art to dark science’: the evolution of digital gerrymandering

In the coming weeks, new technology will play a huge role in mapmakers carve up America’s 435 congressional districts in the US House and even more state and local districts.

> There will also be fewer guardrails in place than ever before; in 2019, the US supreme court said for the first time that there were no federal limits on how severely politicians could draw districts to give their party a political advantage, a practice called gerrymandering.

“What used to be a dark art is now a dark science,” said Michael Li, a redistricting expert at the Brennan Center for Justice. “Before, you weren’t sure about the data, but now you’re much more certain so you’re able to draw things in ways that can be more aggressive.”

Over the last decade, mathematicians and others have also begun to automate the map-drawing.

> New algorithms allow mapmakers to very quickly generate thousands of sample maps based on whatever criteria they input. They could immediately generate thousands of gerrymandered maps, for example, that give one party a significant advantage while also meeting other neutral redistricting criteria like keeping districts compact and meeting the requirements of the Voting Rights Act. The point isn’t necessarily to use a computer to draw a map, experts say, but to explore the possibilities of what’s possible.

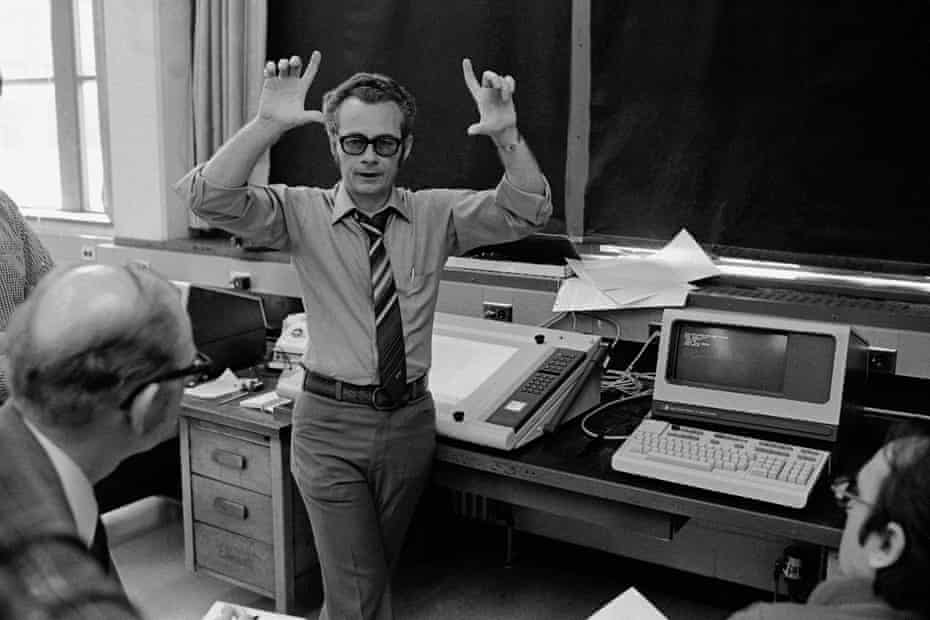

Insert : (1) “That’s a big deal. Sure, there were algorithms 10 years ago, but they were absolute stone age,” said Moon Duchin, a mathematician who leads the MGGG redistricting lab at Tufts University. “You just didn’t have, 10 years ago, good techniques for really seeing a lot of variety and now we do. And that’s a superpower you can use for good or evil.”

Insert : (1) “That’s a big deal. Sure, there were algorithms 10 years ago, but they were absolute stone age,” said Moon Duchin, a mathematician who leads the MGGG redistricting lab at Tufts University. “You just didn’t have, 10 years ago, good techniques for really seeing a lot of variety and now we do. And that’s a superpower you can use for good or evil.”

(2) “I don’t know how to put this nicely – gerrymandering is not really rocket science,” added Samuel Wang, a Princeton professor who leads the Princeton Gerrymandering Project. “You can be reasonably clever and at the level of an excellent checkers player or a reasonably good board gamer and do a good job of drawing a map that confers partisan advantage.”

“You can still build extreme maps, maybe even better than ever. But now we kind of have a method to kind of show that they’re extreme,” Duchin said.

Reformers have already seen how powerful these algorithms can be in fighting gerrymandering.

In 2017, Jowei Chen, a professor at the University of Michigan, used a computer algorithm to draw 1,000 theoretical maps for Pennsylvania’s 18 congressional seats. The algorithm built districts based on “non-partisan, traditional districting criteria”, like keeping county and municipal boundaries intact as well as equalizing populations and keeping districts compact.

Chen also told the algorithm to favor protecting incumbent members of congress. When he compared the 1,000 sample maps to the one Pennsylvania Republicans enacted in 2011, it was clear that the actual map in place was an extreme outlier, far more partisan than if lawmakers were trying to fulfill non-partisan criteria.

When the Pennsylvania supreme court struck down the maps in 2018, the majority pointed to Chen’s analysis as “perhaps the most compelling evidence” the map was so gerrymandered that it violated the state’s constitution. . ."

In 2010, Republicans took advantage of redistricting like they never had before. The party launched a concerted effort, called Project Redmap, to win control of state legislatures and then aggressively drew districts that entrenched Republican control. . .

> While mapmaking has long been done in secret, there’s been an explosion of publicly available, high-quality tools that the public can use to draw districts for free online.

> While mapmaking has long been done in secret, there’s been an explosion of publicly available, high-quality tools that the public can use to draw districts for free online.

> Watchdog groups have also developed easy-to-use online systems that can quickly score maps to see just how gerrymandered they are.

Duchin, the Tufts mathematician, has developed software that allows ordinary citizens in places like Michigan and Wisconsin to their own sample districts to show lawmakers which parts of the state should be preserved.

“One of the big differences from 10 years ago and especially from 20 years ago is the leveling of the playing field, where anybody can have access to voting data and to scoring software that allows the evaluation of a map for fairness or unfairness,” said Wang, whose groups plans to publicly score maps as they are released.

“That’s a big change in the positive direction in terms of pro-democracy and pro-disclosure.”

Those scoring tools, Wang said, will allow a vigilant public to identify gerrymanders that aren’t obvious to the naked eye and hold lawmakers accountable, Wang said.

“The fact that there’s just armies of nerds out there ready to look at these things, ready to … score things, that’s a real change from 10 years ago,” he said."

No comments:

Post a Comment