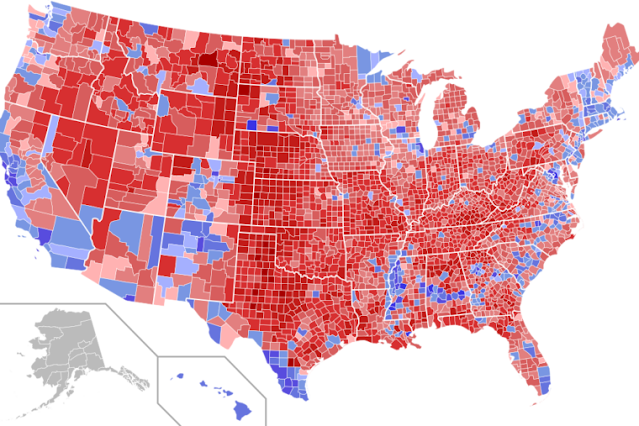

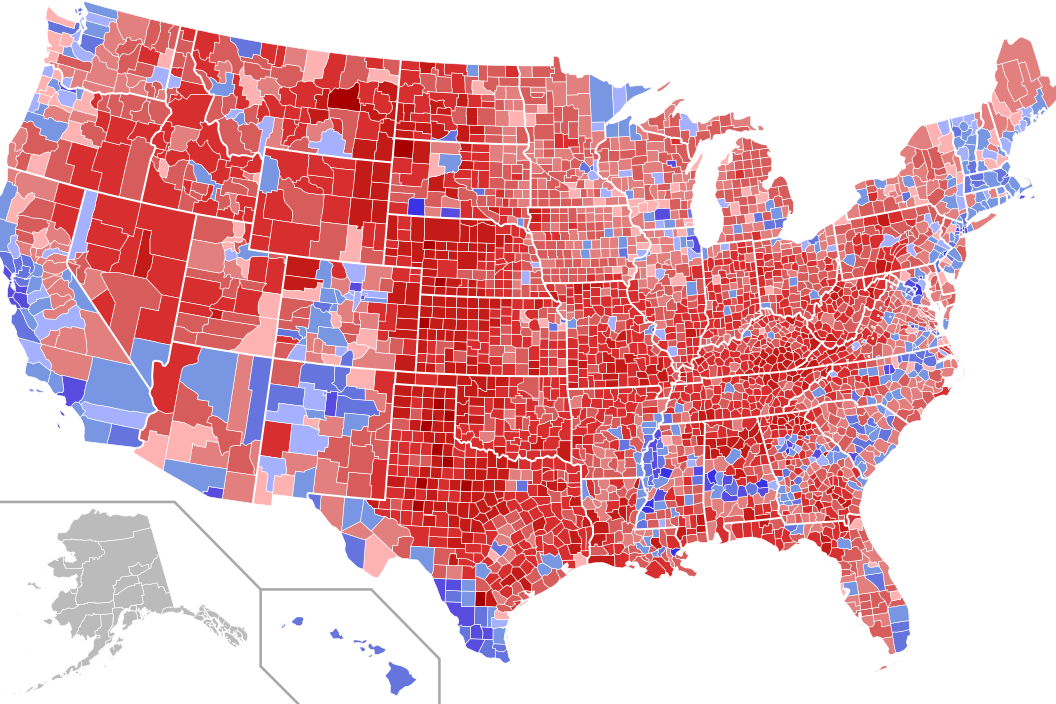

In their research analysis, Reeves and Bryant J. Moy, a PhD candidate in the political science department, along with two University of Maryland co-authors, found that geography is related to substantial differences in partisanship even after accounting for a host of individual traits like age, race, gender, education and religious adherence.

The divide between us: Urban-rural political differences rooted in geography

Research finds how partisan affiliation gets shaped by people’s proximity to a city

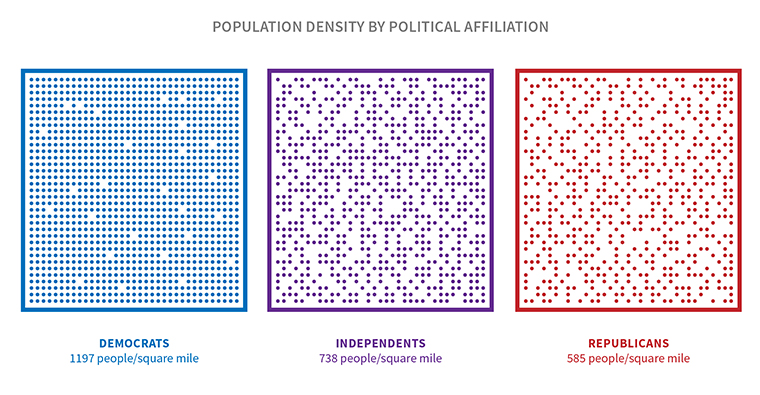

The researchers, using Gallup survey data between 2003-18, found evidence that the urban-rural political divide — more noticeable and decisive in recent elections — is rooted in geography and not merely differences in the type of people living in these places. How close people live to a major metropolitan area, defined as cities of at least 100,000, and their town’s population density play a significant role in shaping their political beliefs and partisan affiliation. The paper will be published in an upcoming issue of Political Behavior.

“However, our research found that the explanation was not that simple.”

... [ ]

“In rural, less populated areas, residents are more likely to know one another and talk with their neighbors. Those interpersonal relationships are highly influential and can create a social pressure to conform,” he said.

“There also is a lot of resentment on the part of rural residents toward urban communities. There is a common perception that cities receive more than their fair share of resources and look down on rural communities.

- The media helps enforce these beliefs with news coverage that predominantly focuses on big cities and the interests of urbanites.”

- In contrast, large, heavily populated cities have traditionally been more open to liberal ideas and more accommodating toward unconventional behaviors and beliefs.

- City dwellers have a greater opportunity to interact with diverse people, which fosters tolerance.

- They also have the ability to be anonymous, which encourages respect for people’s privacy.

- “There is a striking and significant association between geography of residence and party identification,” Reeves said.

- “In both urban and rural settings, geography and population density seem to exert a socializing impact on partisan identification while perhaps also serving as a draw for movers seeking a fitting and compatible destination.”

“By virtue of how we elect our members of Congress and even our president, Democrats are at a disadvantage, and it might only get worse based on the type of campaigning we see going in the primaries.”

Andrew Reeves

“As we have long known, Democratic voters tend to pack themselves into cities, which is inefficient in terms of winning seats or electoral college votes,” he said. “Look at Missouri, for example. St. Louis, Kansas City and Columbia are blue and then the rest of the state is red.

“By virtue of how we elect our members of Congress and even our president, Democrats are at a disadvantage, and it might only get worse based on the type of campaigning we see going in the primaries.

“Many of the Democratic candidates are leaning further to the left. This is not going to win over the rural voters who are more resistant to progressive ideas. The Democratic party is going to be at an increased electoral disadvantage if they decide they want to be the party of the urban progressive.”

Source: WASHU

______________________________________________________________