- How does that earlier period connect to the twenty-first-century history of piracy in Somalia?

- How do we come to grips with this longer span of the history of piracy?

- How does it all fit together?

Houthis Threaten to Target Merchant Ships in Indian Ocean

- Two Houthi spokesmen – Brig. Gen. Yahya Sare’e and Mohammed Abdulsalam – each took to X to post that the Houthis will now target ships linked to Israel traveling in the Indian Ocean on the way to the Cape of Good Hope at the tip of South Africa.

- Commercial vessels have been traversing around the Cape of Good Hope instead of going through the Bab Al-Mandeb Strait and the Red Sea due to Houthi attacks on ships.

“They are putting at risk 12 to 15 percent of the world’s commerce that flows through [the Red Sea]. That doesn’t just impact the United States,” Deputy Pentagon Secretary Sabrina Singh said. “It doesn’t just impact Israel. That affects the entire world, including the people in Yemen.”

Their weapons can go at least 650 kilometers, while the drones can go up to 2,000, Ben Taleblu said. But they cannot hit ships that are going around the Cape of Good Hope.

The Houthis have state-level capabilities as a non-state actor, he said.

“The long leash strategy has always been the secret sauce [for Iran],” Ben Taleblu said

MARCH 16, 2024

Somali pirates begin hijacking ships again after Houthi attacks create security vacuum

Up to £325 million ($413 million) was taken in ransom between 2005 and 2012, according to the World Bank At the height of the crisis pirates were holding 32 vessels and 736 hostages.

OCTOBER 15, 2013

Opinion: The Navy Has Long History of Anti-Piracy Operations

In the early years of this nation, President Thomas Jefferson found himself involved in one of the first conflicts overseas in the First Barbary War.

With several newly commissioned frigates, the Navy would take station in the Mediterranean, off what is known today as Libya, in direct response to the piracy. The buccaneers of the Barbary States were not only seizing our merchant ships, but holding the crews hostage for enormous ransom and forcing them into slavery.

In the fall of 1803, one of the first operations in the Mediterranean was the blockade of the Port of Tripoli. During the operation, the U.S. Navy faced one of its most embarrassing moments in our nation’s early history. Capt. William Bainbridge, commanding the USS Philadelphia, ran the ship aground as it patrolled the channel leading to the port. After several attempts to free the ship, Bainbridge and his crew were captured.

Faced with the embarrassment of the Philadelphia anchored in the harbor of Tripoli, Commodore Stephen Decatur adopted a plan to rescue the ship. Using cover of darkness and flying the British colors, Decatur tacked his flagship, the USS Intrepid, next to the Philadelphia and directed his crew to “board” the ship.

Using innovative tactics that would later be praised by even British Vice Adm. Lord Horatio Nelson, Decatur and his crew overpowered the Tripolitans and reclaimed the Philadelphia. Unable to tow the ship from the harbor due to the lack of winds, Decatur reluctantly set the ship ablaze and retreated to safer waters without a single casualty.

After this remarkable rescue, Stephen Decatur was the name that would be synonymous with any counterpiracy operation that the U.S. Navy would take for the next 200 years. In the spring of 2009, it would be the Aegis-class destroyer Bainbridge that would come to the rescue against the modern-day pirates of Somalia.

With no coast guard to protect its territorial waters from foreign companies fishing the coastal waters off Somalia, several ingenious Somalis decided to form their own coast guard and apprehend the fishing vessels. With great initial success and receiving ransom payments in the tens of thousands of dollars, these modern-day buccaneers decided to expand their operation and capture larger vessels that might pay substantially higher ransoms.

In the summer of 2007, modern-day piracy off the coast of Somalia would become a national security issue for the United States.

- This was not the first merchant vessel that was hijacked by the Somali pirates, but when negotiations were completed, the swashbucklers would receive more than $1 million.

- Not only did the pirates hit it rich, but this event would lead to a major change in the way ships transit through the Horn of Africa.

In 2009, the pirates of Somalia were carrying out a record number of attacks and hijackings off the Horn of Africa.

- Despite the efforts of naval task forces from the European Union, NATO and the United States, these buccaneers had the upper hand. . .

After Red Sea, Houthis Could Attack Ships in the Indian Ocean

Exploring the History of Piracy

Sarah, when we think about piracy, we tend to think about the sixteenth-century Atlantic world or the Caribbean – the age of European imperialism, and the spread of multiple states westwards across the Atlantic.

How does that earlier period connect to the twenty-first-century history of piracy in Somalia? How do we come to grips with this longer span of the history of piracy? How does it all fit together?

It doesn’t magically click together, but then, nothing in history does! Still, across the centuries there are important similarities and common factors that cause piracy to emerge in different parts of the globe. And the first and most significant is that all pirates must have a favorable geopolitical environment.

Thinking about geography first, pirates need a reliable and predictable stream of potential targets.

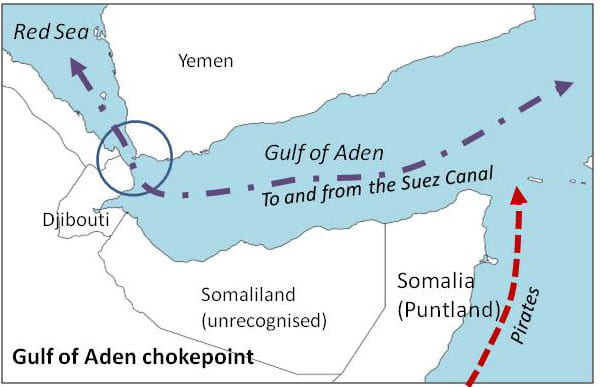

One way to find ships is to hang around a ‘chokepoint’ – which is a fancy military term for a bottleneck. From an oceangoing perspective, chokepoints are formed by narrow channels between landmasses that force ships to isolate themselves from one another in order to pass through.

- This passage provides the only entrance to the Mediterranean Sea from the Atlantic Ocean, and it’s only 14 kilometres across.

- For centuries, the Mediterranean was a major trade route for European goods.

- This sea trade moved under sail and the narrow passage forced ships to group around the entrance to the straits to await the favorable winds and currents that allowed them to sail through.

- Their enemies often considered them pirates but, strictly speaking, they don’t fit the actual definition of a pirate, namely, a sea-raider who carried no commission at all.

The corsairs would sail up from the south, and they’d be able to pick off the targets individually and chase them down, because they knew that they’d be trying to get through this channel to reach the Mediterranean trading routes.

- These islands break up the clear expanse of water, and they forced trading ships through a predictable route to their island trading posts, dictated partly by the winds and the currents that pushed them through in a particular direction.

- Pirates would hide out on the other side of the islands, lay in wait, and then chase the ship down and attack it.

- As you sail up the Gulf of Aden, you’re forced through the Bab al-Mandab Strait, which runs between Djibouti and Yemen.

- In order to pass through, the ships need to self-isolate, and that makes it easier for Somali pirates to pick off the merchant ships as they come through.

- So we find similarities in all these different cases.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment