Russia’s success in evading Western sanctions has helped its economy far outperform expectations ahead of Vladimir Putin’s all but certain re-election on Sunday.

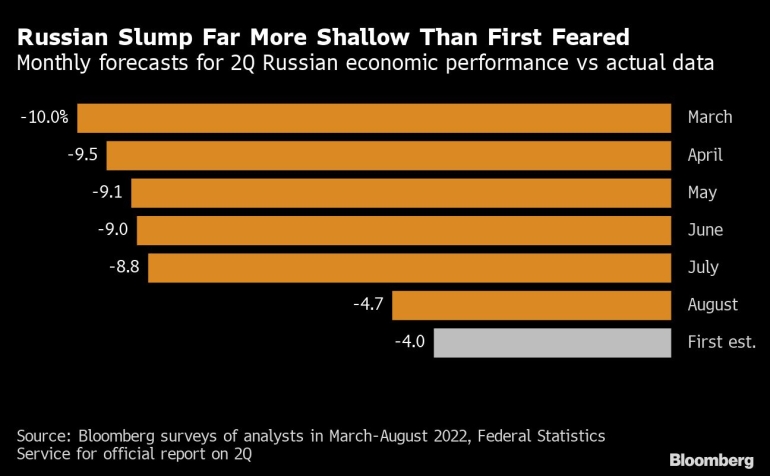

Ever since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the Russian economy has consistently defied the dire predictions of critics.

Ever since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, the Russian economy has consistently defied the dire predictions of critics.

As Putin eyes sure reelection, Russia’s economy defies sanctions, critics

Russian president’s all but guaranteed fifth term in power comes as economy has outperformed expectations.

That resilience appears to be holding firm as Russians head to the polls between Friday and Sunday for a presidential election that is set to ensure Putin’s rule until at least 2030.

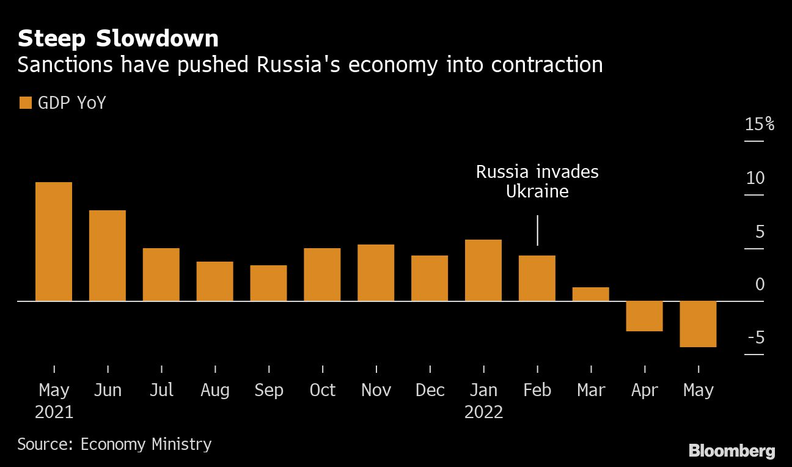

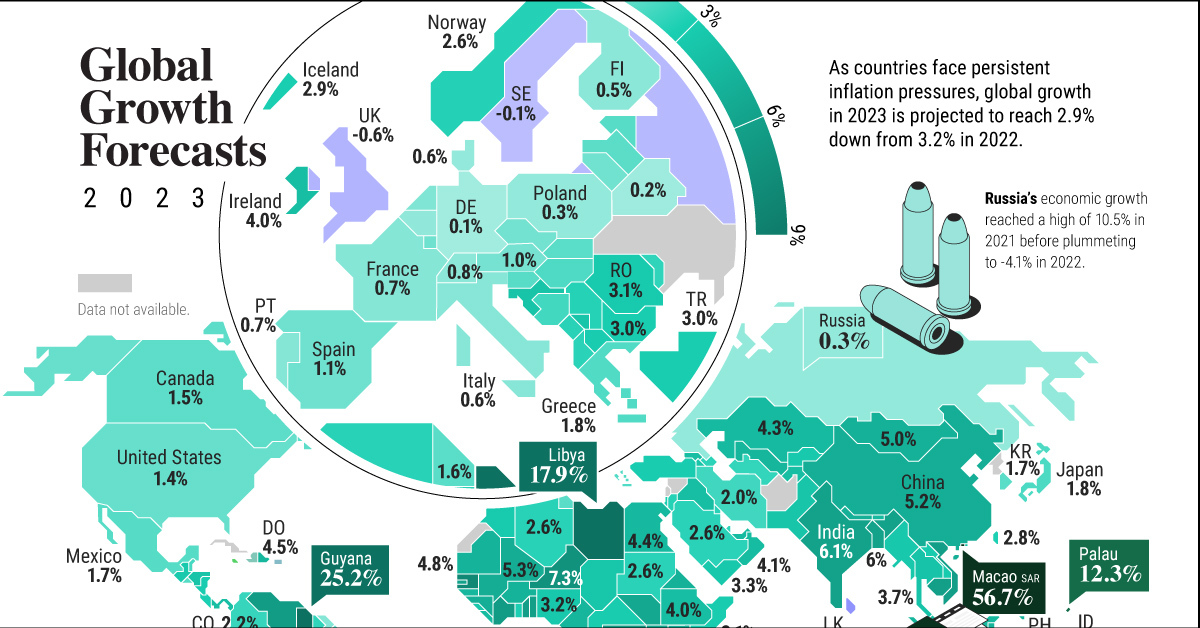

At the start of the war, the International Monetary Fund expected a prolonged recession, forecasting the economy to contract by 8.5 percent in 2022 and 2.3 percent in 2023.

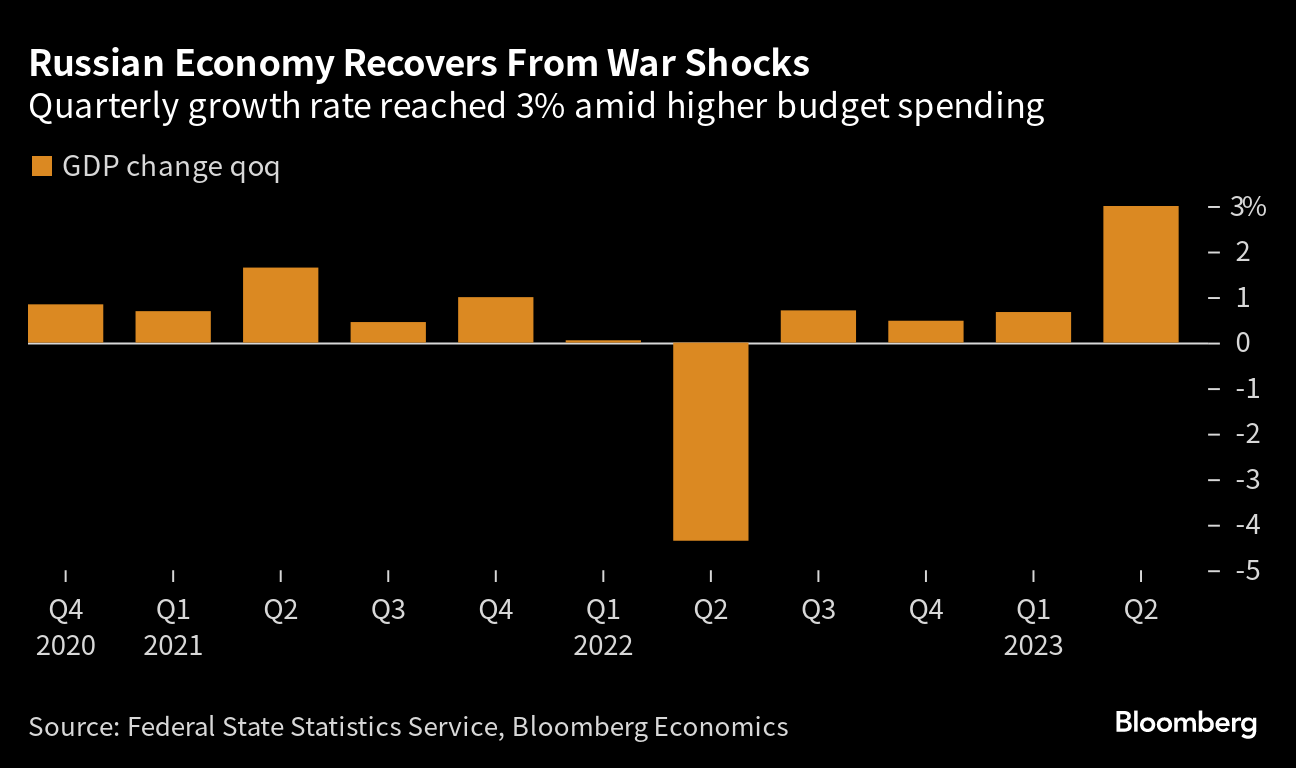

- While Russia’s economy did shrink in 2022, the contraction was just 1.2%, according to government figures.

- Last year, the economy officially grew 3.6 percent%

According to Castellum.AI, a global risk platform, Russia has been slapped with 16,587 sanctions since the start of the war – the majority of them against individuals.

- Some $300bn of Russian assets have been frozen.

Owing to high oil prices and elevated military spending, Russia has managed to mitigate much of the impact of sanctions. But the costs of prolonged conflict, and the possibility of yet more sanctions, look set to weaken output over the medium term.

“Extra spending unleashed by war can boost economic activity. But it also represents a redistribution of income away from state services towards the army,” Konstantin Sonin, a political economist at the University of Chicago, told Al Jazeera.

- Military spending has swelled in recent years, rising from 3.9 percent of the gross domestic product in 2023 to about 6 percent in 2023 – the highest it has been since the collapse of the Soviet Union.

- This year, military expenditure is expected to account for almost one-third of government outlays.

Meanwhile, Russia’s massive energy sector has kept money flowing into state coffers, while local companies have made substantial efforts to substitute Western imports. . .

- “Most critically, Russia has continued to sell plenty of fossil fuels. It’s true that oil and gas exports have fallen because of sanctions, but elevated prices have kept overall revenues high,” he said.

- Sonin added that “it’s important to recall the size of Russia’s fossil fuels sector. Domestically, oil accounts for roughly one-third of tax receipts and half of all export revenue”.

The Kyiv School of Economics estimates that Moscow made $178bn from oil sales last year and that revenues could rise to $200bn in 2024 – not far off the $218bn earned in 2022.

In May 2022, the European Union agreed to cut 90 percent of its oil imports from Russia. Then, in December 2022, Australia and G7 members announced a price cap on Russian crude oil – known as Urals crude – aiming to squeeze Moscow’s finances even further.

Under the rules, non-G7 oil traders can only use Western ships and finance or insurance services provided they pay $60 per barrel, or less – well below the market-rate.

Under the rules, non-G7 oil traders can only use Western ships and finance or insurance services provided they pay $60 per barrel, or less – well below the market-rate.

But Russia has proved adept at countering these measures, according to Switzerland-based energy trader Mohammed Yagoub.

“Russia has built up a large ‘shadow fleet’, which are tankers with opaque ownership and no Western ties in terms of finance or insurance. In addition, Russia has found plenty of non-Western oil buyers at discount prices, China and India most notably,” Yagoub told Al Jazeera.

“Last month, the majority of Russian Urals were sold above $60. But, Western countries have been clamping down,” Yagoub added, pointing to a reported information request from the US Treasury to shipping companies suspected of violating the cap.

“Over the past year, the Kremlin’s been lucky. Western countries don’t want to snuff out Russian oil altogether, because a supply crunch would trigger global inflation. So, they’ve just chugged along much as they were before the war.”

“Russia has built up a large ‘shadow fleet’, which are tankers with opaque ownership and no Western ties in terms of finance or insurance. In addition, Russia has found plenty of non-Western oil buyers at discount prices, China and India most notably,” Yagoub told Al Jazeera.

“Last month, the majority of Russian Urals were sold above $60. But, Western countries have been clamping down,” Yagoub added, pointing to a reported information request from the US Treasury to shipping companies suspected of violating the cap.

“Over the past year, the Kremlin’s been lucky. Western countries don’t want to snuff out Russian oil altogether, because a supply crunch would trigger global inflation. So, they’ve just chugged along much as they were before the war.”

Russia has also found ways to skirt import restrictions by sourcing goods from countries acting as intermediaries for Western goods. For instance, Serbia’s exports of phones to Russia rose from $8,518 in 2021 to $37m in 2022.

Some observers dispute the suggestion that the pressure campaign against Moscow has failed. . ."

Some observers dispute the suggestion that the pressure campaign against Moscow has failed. . ."

==========================================================================

RELATED

.gif)

No comments:

Post a Comment