Related questions

How much of the promised land is occupied today?

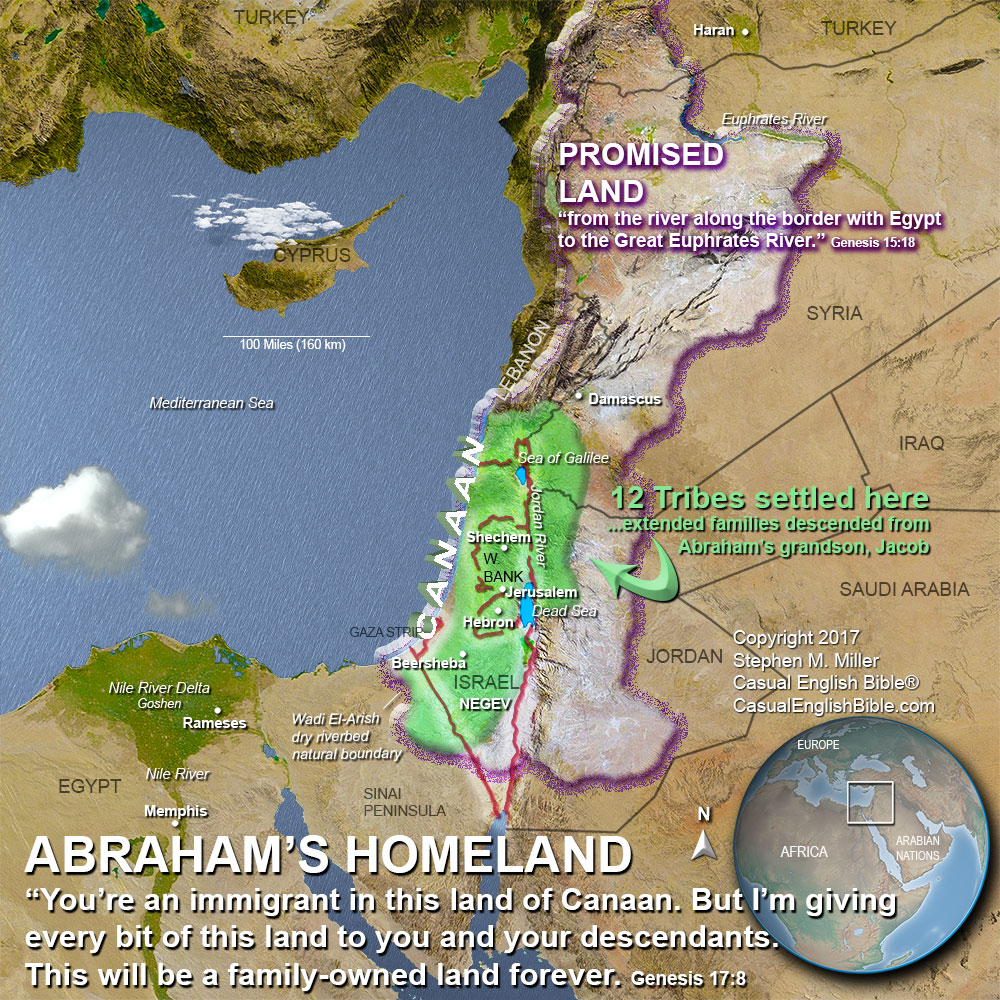

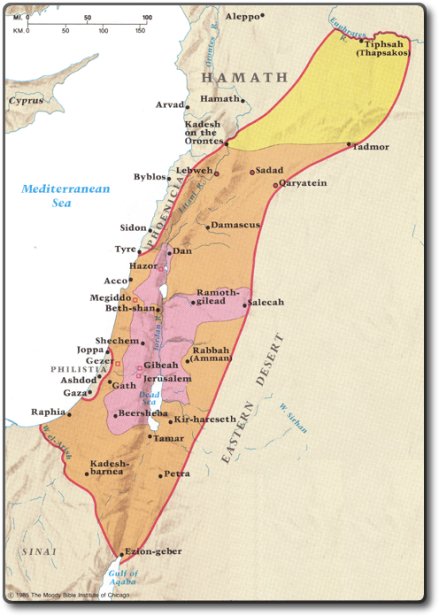

In Genesis 15:18 Yahweh promises that He has given Abraham and his descendants the land ‘from the river of Egypt to the great river, the Euphrates.’

- The northern and southern boundaries are not that well defined, but the rivers do give the east and west.

- Even the west bank of the Jordan is disputed territory, despite it being the heartland of the Biblical tribal placements.

- The land currently referred to as the West Bank is actually a large chunk of the Biblical Israel and Judah.

In Chapter 15, God deeds Abraham a specific geographical area of land according to the ancient customs of that time. It is absolutely crucial to understand that this was God’s promise to Abraham. This was not a mutual agreement. God literally deeded the land to Abraham and the nation of Israel. So it will happen. God said it; believe it.

In Genesis 12:1-3, God makes a covenant with Abraham, also known as the Abrahamic Covenant, in which He promises to bless Abraham and make him a great nation, and in turn Abraham’s descendants will be a blessing to all nations. . .

- This promise of land to the descendants of Abraham is reinforced throughout the Bible, and it is often cited as the reason for the ongoing Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

- However, interpretation of these promise and it’s application today is a subject of ongoing debate and there are different perspectives on what it means for modern nation-states.

____________________________________________________________

History of Ancient Palestine

Ancient Palestine was only a small land, insignificant when compared with the great empires of the Ancient World – Assyria, Babylon, Persians so on. But it had a more direct impact on later world history than any of them, and remains profoundly influential to this day.

Introduction

By the 3rd millennium BCE, the southern Levant was a land of small, fortified towns and villages, ruled over by petty kings and chiefs. Indeed, the earliest remains of a community which can, with any sense of the modern term, be called a “town” have been found in the region, at Jericho. These date back to 7000 BCE, not very long after farming first began to be practiced.

A major trade route connecting Mesopotamia with Egypt (later known as the King’s Highway) ran south from Damascus through the Jordan valley. Urbanism, along with Bronze Age technology, had presumably arrived in this region via trade links with Mesopotamia. In any event, urban civilization began to flourish here not long after it had begun in Egypt.

Nomadism had also made its appearance, with pastoralist clans grazing their sheep on the eastern hill country and in the grasslands between the settled areas.

The Land of Canaan

The inhabitants of the land belonged to numerous small groups of settled farmers and nomads. However, in Egyptian and, later, Biblical literature they are usually called by the hold-all label “Canaanites”. It does seem that they spoke a common language, belonging to a branch of the Semitic family of languages and closely related to modern Hebrew. They also possessed a common material culture, which owed much to the Egyptian civilization to the southwest, with Mesopotamian traces from the east as well. Their religion, however, seems to have been entirely indigenous, with an emphasis on sexualized worship of their gods (baals) and including the practice of human sacrifice, particularly of young children.

In the later 3rd millennium, the towns of Canaan declined, many vanishing altogether. Pastoral nomadism became the dominant economy. This was at around the same time as the Amorites, Hurrians and other groups were moving into northern Syria. The upheavals of the period may well have caused groups of Canaanites to enter Egypt at this time, eventually bringing the Nile Delta in northern Egypt under their control. They appear in Egyptian history as the “Hyksos”.

The Fall of the Kingdom of Israel

The division of Israel into two kingdoms weakened them both. The Aramaeans quickly broke away from Israelite dominance, and their kingdom based on Damascus soon became one of Israel’s most powerful enemies. The Philistine city-states and the kingdoms of Edom, Moab and Ammon also regained their independence.

From the mid-8th century all the kingdoms of the region came under increasing threat from the expanding Assyrian empire. This culminated in the later 8th century: first the kingdom of Damascus, in 732, then the kingdom of Israel, in 722, were extinguished by the Assyrians. Their capitals were destroyed, and both Biblical and Assyrian sources speak of massive deportations of people from Damascus and Israel. Replacement settlers were brought in from other parts of the empire. Such population exchanges were an integral part of Assyrian imperial policy, as a way of breaking old centers of power.

According to an Assyrian inscription, the number of Israelites transported from their homeland amounted to just over 27,000. Even taking into account a large-scale emigration to the southern kingdom, the majority of the population were still presumably left in place. However, groups from other parts of the Assyrian empire were settled in the area by the Assyrian authorities. These apparently soon adopted the Israelite worship of Yahweh, perhaps modified in some details. They intermarried with the native inhabitants and became the ancestors of the Samaritans.

The territory of the old kingdom of Israel became the Assyrian province of Samaria. It seems to have been under a line of governors drawn from local families.

The other states of the area – the Philistine city-states and the kingdoms of Judah, Edom, Moab and Ammon – escaped the fate of Israel by becoming tributary states of Assyria. The Assyrian records show that these kingdoms were sometimes loyal, sometimes disloyal, to their Assyrian overlords. All these kingdoms rebelled against Assyria in about 701 BCE, but the anti-Assyrian alliance soon seems to have fallen apart in the face of a massive invasion by the Assyrian army under king Sennacherib. Most of the kingdoms hurriedly resumed their submission to Assyria, but Judah was slower to do so, and the Assyrians lay siege to Jerusalem. Judah survived the assault (miraculously, according to the Bible, but not without large-scale destruction round about, as the archaeological evidence shows). After this, the kings of Judah became vassals of the Assyrian king again, and were left in peace.

The destruction of the kingdom of Israel had a deep impact on the kingdom of Judah. A stream of refugees from Israel flooded into the kingdom, boosting its population. In the 7th century, Jerusalem expanded dramatically. However, Judah was now the only Israelite kingdom left, surrounded entirely by pagan peoples. Perhaps because of this, the rulers of Judah tended to emphasize the worship of Yahweh as a central part of their political program. A state-sponsored religious reform movement culminated in the reign of king Josiah (reigned 641-609 BCE), which centered the religious life of Judah much more firmly on the Temple in Jerusalem, and called for a greater degree of obedience from the people to the faith’s teachings.

The Fall of the Kingdom of Judah

By this time, however, large-scale geopolitical developments were reshaping the political situation in the whole of the Middle East. The central event in this was the sudden collapse of Assyrian power in the decades after the 630s, in the face of multiple revolts by its subject peoples.

For a brief period, the kingdom of Judah benefited from the resulting vacuum of power in the Middle East by expanding its own borders to take in much of the old territory of Israel. However, a new regional superpower rapidly emerged, that of Nebuchadnezzar, king of Babylon. The struggle between the Babylonian empire and a resurgent Egypt for control of Syria and Palestine led, as a by-product, to the conquest of all the kingdoms of Palestine by Nebuchadnezzar in a series of campaigns between 597 and 582.

The Babylonian period

Under the Babylonians, most Palestinian rulers remained in place, now as vassals of the king of Babylon. The exception was Judah, which, thanks to its repeated resistance to the Babylonians, experienced catastrophe. The kingdom was extinguished; its political and religious elite were taken off to exile in Babylon; the Temple in Jerusalem was destroyed, and much of the city with it; and the territory of the former kingdom, shorn of outlying districts (hived off to neighboring kingdoms), was turned into the province of Judea, under governors appointed by the Babylonians. Jerusalem was stripped of any administrative status, with the town of Mizpah, to the north, being made the provincial capital.

Only a minority of the population were taken into exile in Babylon. Thousands more emigrated to Egypt, and from this time on communities of Jews began appearing in cities throughout the Middle East and beyond.

For those who remained in Judea, life was tough. The violent cycle of Jewish rebellion and Babylonian counter-measures had devastated many towns and villages, and had led to a significant drop in population and prosperity.

Two Great Revolts

In Judea itself, the Romans had encountered continual trouble in governing the province. A particular source of tension was the arrival of large numbers of Greek-speaking settlers from other parts of the empire and the consequent spread of Hellenistic culture in the area. Trouble between Jews and Hellenists was never very far away. This situation was more or less contained (albeit with the outbreak of a couple of localized rebellions, soon put down) for many years; however, with the appointment of a Roman governor who had complete disregard for Jewish religious feelings, a fierce revolt flared up, in 66 CE. This soon engulfing the entire province, and became a major challenge to Rome’s hold on its eastern frontiers. The Roman army had to commit large numbers of troops to stamping it out. It was finally defeated in 73 CE, by which time much of Jerusalem and almost the entire Temple, the center and focus of the Jewish faith, lay in ruins.

The Samaritan community, which had not participated in the revolt, suffered in the aftermath: a new Hellenistic colony, Neopolis (modern Nablus) was founded at their traditional religious center of Mt Gerizim, as a boost to the Greek-speaking population in the area.

In 133, a second great Jewish revolt broke out, led by a charismatic leader called Simon Bar Kochba.

Bar Kokhba silver Shekel/tetradrachm.

The text reads “To the freedom of Jerusalem”

Reproduced under Creative Commons 3.0

This was sparked by the emperor Hadrian’s plan to establish a Roman colony on the old site of Jerusalem. The revolt involved bloodshed on a massive scale as the Romans systematically reimposed their authority (which they had achieved by 136).

After this, the Jews were banned from living in in or near Jerusalem. Jerusalem itself was rebuilt as a Roman colony. Even the name “Judea” disappeared as a Roman administrative label, with the province now being called Syria Palaestina.

Palestine in the later Roman empire

The Roman attempt to keep the Jews out of their old homeland after the Bar Kochba revolt had never been wholly successful, and small Jewish communities gradually reappeared (if they had ever gone away). Indeed, their existence was recognized by the granting of certain privileges, such as exemption from the imperial cult and internal self-administration. Also, it was not long before they were granted the right to visit Jerusalem (Aelia Capitolina) on certain feast days.

In any case, the areas surrounding Judea, especially Galilee, had not been subject the ban, and the Jewish population had remained there unmolested; and Samaria remained home to the Samaritan community.

- In the mid-3rd century, Palestine was caught up in the disasters which beset the Roman frontier at that time. For several years, in the 260s and early 270s, the province was under the control of the separatist regime of Zenobia, Queen of Palmyra, until restored to the empire by the emperor Aurelian in 272.

With the coming of Christian emperors to the throne after 324, Palestine’s status was transformed. As the location for the life and mission of Jesus of Nazareth, and the place where Christianity started, it began to receive lavish attention from the imperial family.

Many fine churches were built. Aelia Capitolina came again to be called Jerusalem, and its bishop became one of the four or five most senior bishops – or patriarchs – of the Christian Church. Many of the earliest Christian monasteries outside Egypt were founded in Palestine, which became a major center of Christian scholarship.

The area naturally attracted many Christian pilgrims. This contributed to the prosperity which Palestine experienced in the Later Roman Empire. Towns and cities thrived, farmland was extended by irrigation projects, and the population expanded.

- In 351-2 the Jews of Galilee engaged in a short-lived revolt against the Roman authorities. This seems not to have affected their status in the long term, and in 438 Jews were allowed to return to live in Jerusalem itself. The Samaritans were not so fortunate. In the late 5th century they came under official pressure to convert to Christianity, which sparked a series of revolts and the inevitable reprisals.

_

No comments:

Post a Comment