Gravitational waves from star-eating black holes detected on Earth

Spacetime-altering shock waves came from massive neutron stars crashing into black holes millions of years ago

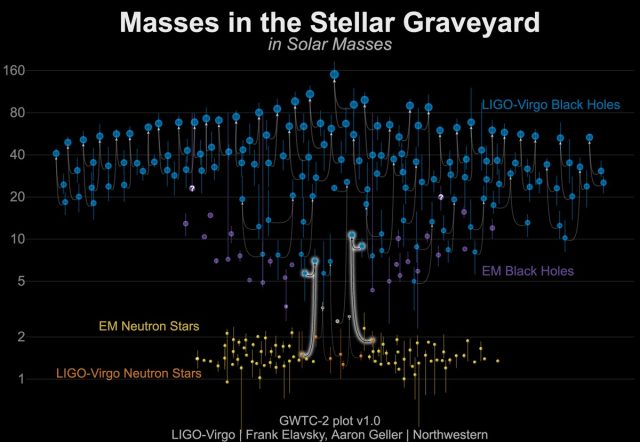

Years after scientists began their search for quivers in spacetime anticipated by Albert Einstein, gravitational wave detectors in the US and Europe have detected the first signals from two neutron stars crashing into black holes hundreds of millions of light years away.

“We are talking about objects that have more mass than the sun that have been gobbled up,” said Dr Vivien Raymond at Cardiff University’s Gravity Exploration Institute. “We would like for the neutron stars to be ripped apart and shredded because then there’s a lot of opportunity for interesting physics, but we think these black holes were big enough that they swallowed the neutron stars whole.”

. .

Gravitational waves pass through Earth all the time, but the shudders in spacetime are too subtle to detect unless they are triggered by collisions between extremely massive objects. Scientists reported the first detection of gravitational waves from the collision of two black holes in 2016 and have since spotted waves from neutron star mergers. Recording gravitational waves from neutron stars hitting black holes marks another first.

“With these events, we’ve completed the picture of possible mergers amongst black holes and neutron stars,” said Chase Kimball, a graduate student at Northwestern University in Illinois. “That doesn’t mean that there are no new discoveries to be made with gravitational waves. There are plenty of expected gravitational wave sources out there that we’ve yet to detect, from continuous waves from rapidly rotating neutron stars to bursts from nearby supernovae, and I’m sure the universe can find ways to surprise us.”

===================================================================

2

Physicists confirm two cases of “elusive” black hole/neutron star mergers

When a neutron star and a black hole love each other very, very much....

"With this new discovery of neutron star-black hole mergers outside our galaxy, we have found the missing type of binary," said co-author Astrid Lamberts of CNRS, a researcher on the Virgo collaboration in Nice. "We can finally begin to understand how many of these systems exist, how often they merge, and why we have not yet seen examples in the Milky Way."

"With this new discovery of neutron star-black hole mergers outside our galaxy, we have found the missing type of binary," said co-author Astrid Lamberts of CNRS, a researcher on the Virgo collaboration in Nice. "We can finally begin to understand how many of these systems exist, how often they merge, and why we have not yet seen examples in the Milky Way."

LIGO detects gravitational waves via laser interferometry, using high-powered lasers to measure tiny changes in the distance between two objects positioned kilometers apart. LIGO has detectors in Hanford, Washington state, and in Livingston, Louisiana. A third detector in Italy, Advanced VIRGO, came online in 2016. In Japan, KAGRA is now online, and it's the first gravitational-wave detector in Asia and the first to be built underground. Construction began on LIGO-India earlier this year, and physicists expect it will turn on sometime after 2025.

To date, the LIGO collaboration has detected dozens of merger events since its first Nobel Prize-winning discovery, all involving either two black holes or two neutron stars. Most recently, last year, the collaboration announced the detection of two more black hole mergers. One was the most massive and most distant black hole merger yet detected, and it produced the most energetic signal detected thus far. It showed up in the data as more of a "bang" than the usual "chirp." The detection also marked the first direct observation of an intermediate-mass black hole.

As the detectors' sensitivity improves, confirmed events are becoming much more frequent. . ."Following the tantalizing discovery, announced in June 2020, of a black-hole merger with a mystery object, which may be the most massive neutron star known, it is exciting also to have the detection of clearly identified mixed mergers, as predicted by our theoretical models for decades now," said co-author Vicky Kalogera of Northwestern University. "Quantitatively matching the rate constraints and properties for all three population types will be a powerful way to answer the foundational questions of origins."

. . .“These were not events where the black holes munched on the neutron stars like the Cookie Monster and flung bits and pieces about.. .That 'flinging about' is what would produce light, and we don't think that happened in these cases."

. . .

"We've now seen the first examples of black holes merging with neutron stars, so we know that they're out there," said co-author Maya Fishbach, also from Northwestern. "But there's still so much we don't know about neutron stars and black holes—how small or big they can get, how fast they can spin, how they pair off into merger partners. With future gravitational wave data, we will have the statistics to answer these questions, and ultimately learn how the most extreme objects in our universe are made."

DOI: The Astrophysical Journal, 2021. 10.3847/2041-8213/ac082e (About DOIs).

. . .

No comments:

Post a Comment