In 2015, researchers used GRACE satellite data and other sources to show that the Arabian Peninsula ranked as the most stressed of the world's 37 largest aquifers. . . Saudi Arabia has squandered it's underground Aquifers

"The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia spans 2.1 million square kilometers (830,000 square miles)—an area larger than Alaska and Texas combined—yet it has no permanent rivers or standing lakes. What it does have are wadis, valleys that are transformed into ephemeral rivers after storms, and aquifers with groundwater.

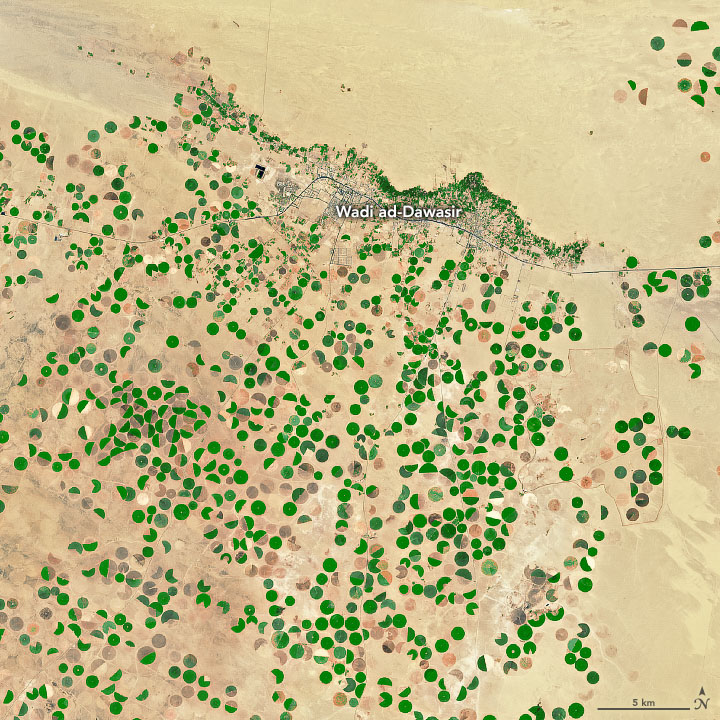

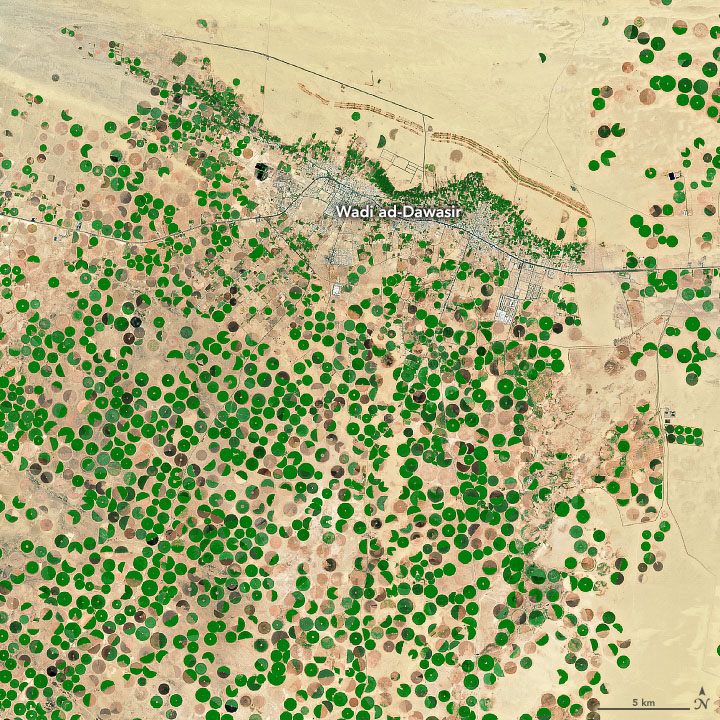

This pair of images captures the spread of agriculture around the town of Wadi ad-Dawasir. Groundwater and irrigation have been used to green-up portions of the desert in Saudi Arabia. The images were acquired by the Advanced Spaceborne Thermal Emission and Reflection Radiometer (ASTER) on NASA's Terra satellite in 2000 and 2017.

✓ Since the area receives less than 200 millimeters (8 inches) of rain per year, farmers make use of pumped groundwater and center-pivot irrigation systems to grow crops—mainly wheat, alfalfa, and vegetables.

Carbon-14 dating indicates that the groundwater being used is more than 30,000 years old; hydrologists consider it to be paleowater or “fossil water.” The sustained pumping of this water has had a major impact on the aquifer beneath Wadi ad-Dawasir.

✓ According to one United Nations report, the water table in this area has dropped by as much as 6 meters (20 feet) per year since the 1980s, fast enough that hydrologists think the aquifer could be depleted within a few decades.

In 2015, researchers used GRACE satellite data and other sources to show that the Arabian Peninsula ranked as the most stressed of the world's 37 largest aquifers. In September 2019, another GRACE-based study pointed out that the problem is particularly severe in the central and northern part of the aquifer, which includes Wadi ad-Dawasir.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens, using data from NASA/METI/AIST/Japan Space Systems, and U.S./Japan ASTER Science Team. Story by Adam Voiland.

When Haji Nazeer Ahman Qazi opened his cellphone, he received a text message that would help him manage the ten acres of wheat growing on his farm near Sargodha, Pakistan. The text message—beginning “Dear farmer friend”—stated that 1.3 centimeters (0.5 inches) of rainfall were expected in his area in the upcoming week. Those few words would help him save water and improve his crop yield.

“Keeping in view of the expected rainfall and last week’s water consumption, I skipped my last irrigation for wheat,” recounted Qazi. “The rainfall forecast proved right, which not only saved me irrigation, but protected [my] wheat from waterlogging, as nearby farmers suffered.”

Qazi is one of 20,000 farmers who receive weekly text messages from the Pakistan Council of Research in Water Resources (PCRWR). The notifications, partly based on NASA satellite data, provide information on current and future weather conditions, as well as advisories on how to water certain crops. The texts are designed to help prevent a serious problem facing Pakistani farmers: overwatering.

“Farmers are giving 40 to 50 percent more water than what is needed,” said Faisal Hossain, the head of the Sustainability, Satellites, Water, and Environment (SASWE) research group at the University of Washington. “The overwatering comes from what they have learned from their fathers and grandfathers, from an era when water was abundant.”

Hossain and his colleagues are collaborating with the PCRWR to analyze satellite data, ground-based measurements, and weather models to calculate how much water various crops will need and how much they are likely to get. The PCRWR Irrigation Advisory system, initially funded by NASA’s Applied Science Program, distributes this information via text alerts with simple messages such as: “We would like to inform you that the irrigation need for your banana crop was 2 inches during the past week.” Each simple message is derived from a complex analysis of numerous weather variables.

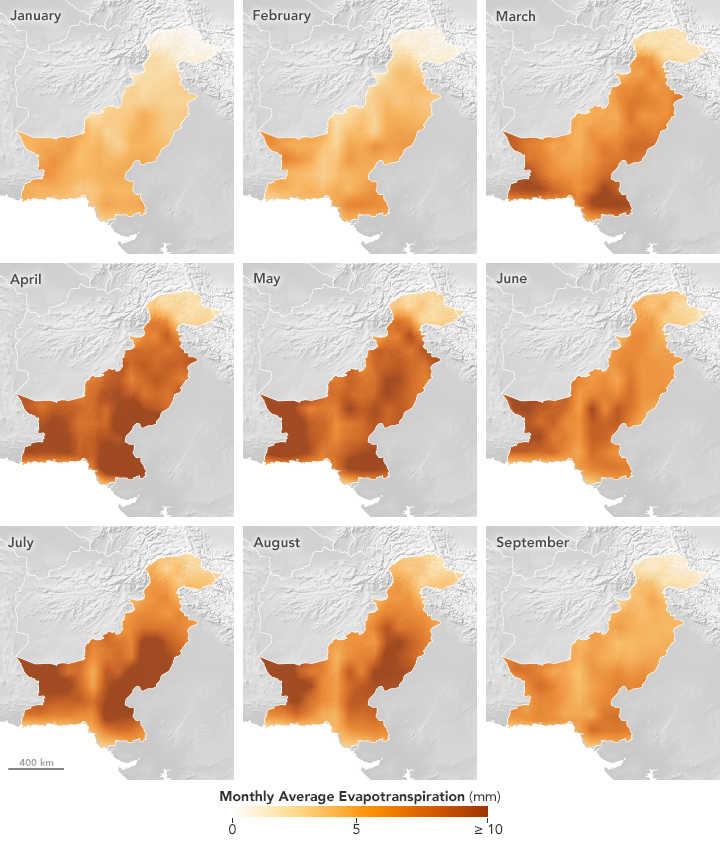

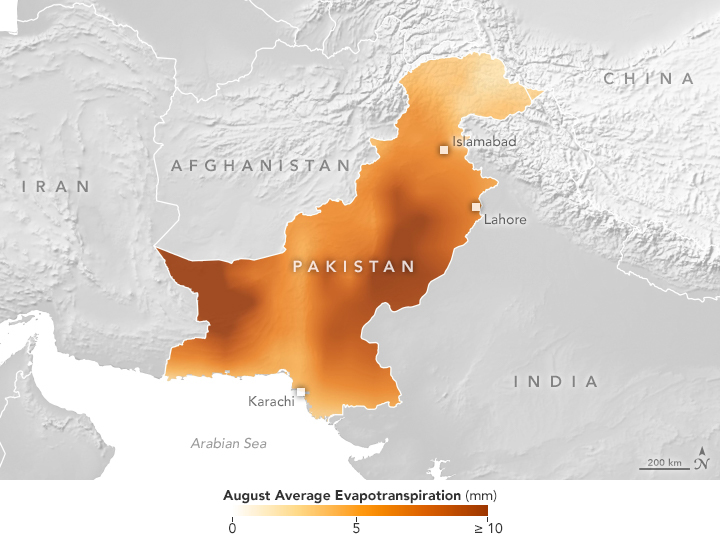

The maps on this page show one of those variables, evapotranspiration, which is an indication of the amount of water vapor being removed by sunlight and wind from the soil and from plant leaves. Hossain’s team uses evapotranspiration to assess the water demand for specific crops.

References & Resources

- EOS (2019, November 5) Arid Arabian Peninsula Is Tapping into Vast Groundwater Reserves. Accessed December 12, 2019.

- Foreign Affairs (2015, November 10) The Other Liquid Gold. Accessed December 12, 2019.

- Inventory of Shared Water Resources in Western Asia (2013) Wajid Aquifer System. Accessed December 12, 2019.

- NASA Earth Observatory (2015, July 24) Global Groundwater Basins in Distress. Accessed December 12, 2019.

- National Geographic (2015, November 10) Saudi Arabia’s Great Thirst. Accessed December 12, 2019.

- Richey, A. et al. (2015) Quantifying renewable groundwater stress with GRACE. Water Resources Research, 51 (7), 5217-5238.

- Smart Water Magazine Saudi Arabia’s groundwater to run dry. Accessed December 12, 2019.

- Sultan, M. et al. (2019) Assessment of age, origin, and sustainability of fossil aquifers: A geochemical and remote sensing-based approach. Journal of Hydrology, 576, 325-341.

RELATED CONTENT

Saudi Arabia squandered its groundwater and agriculture collapsed. California, take note.

Many of the world's most important farming regions can't rely on rain alone to water all their crops. So they also pull freshwater from underground aquifers that have slowly filled up over many thousands of years. Notable examples include the Central Valley in California or the Indus Basin in Pakistan and India.

The problem is that these underground aquifers take a long, long time to recharge. So if farmers are drawing water faster than it gets replenished, the basins will eventually run dry..."

READ MORE

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment