Two new AI-based weather-forecasting systems challenging the status quo

The first team, made up of engineers at Huawei Cloud, in China, built a system called Pangu-Weather. It was designed to predict weather a week in advance. The second team, with engineers from Tsinghua University, in China, working with one colleague from the China Meteorological Administration and another from the University of California, Berkeley, has built a system called NowcastNet. It was designed to predict precipitation levels for the upcoming six hours.

Both teams have published papers in the journal Nature describing their systems and how well they have done during testing trials. Imme Ebert-Uphoff and Kyle Hilburn with the Cooperative Institute for Research in the Atmosphere at Colorado State University, have published a News & Views piece in the same journal issue outlining the challengers of building AI weather-predicting systems and the work done by the teams on these two new efforts.

Currently, the most reliable form of weather-forecasting comes courtesy of numerical models that accept current weather data and apply math and physics formulas to make predictions about upcoming weather. Such systems are considered to be quite reliable, at least for major metropolitan areas—but they are CPU intensive, taking hours to calculate results.

But because weather forecasting is so important to farmers and for providing warning of dangerous storms, scientists continue to look for ways to improve prediction results. One promising area of research is AI—where instead of running formulas, systems are given historic weather data and use it to make predictions about the future.

In the first effort, the team behind Pangu-Weather, trained their system on 39 years of weather data and then asked it to make predictions based on current weather patterns. They found that it was as accurate at doing so as existing systems, and did its work in just a fraction of the time.

But it does suffer from one major drawback—it does not make any predictions about precipitation amounts. Instead, it returns estimates of temperature, wind speed, air pressure and other weather-related data. Humans are then left to make prediction estimates based on what the system shows them.

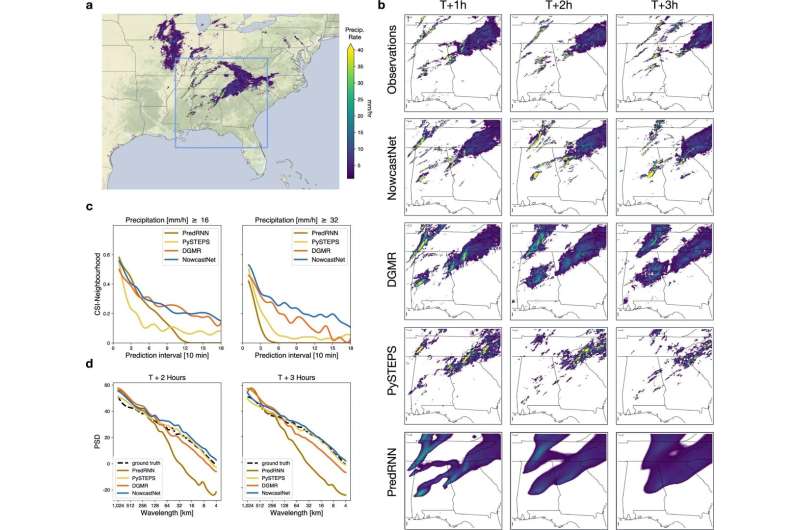

NowcastNet, on the other hand, does just the opposite—it tries to give accurate predictions about the amounts of precipitation a given area will receive in the upcoming six hours. It does so using both historical data and physical rules. It too proved to be as accurate as conventional systems and also returned results much faster than conventional systems.

Both teams note that their systems are currently still at the test-of-principle stage but also suggest that their results thus far hint at the possibility of AI-based weather predicting soon becoming the standard approach.

More information: Yuchen Zhang et al, Skilful nowcasting of extreme precipitation with NowcastNet, Nature (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-023-06184-4

Kaifeng Bi et al, Accurate medium-range global weather forecasting with 3D neural networks, Nature (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-023-06185-3

Imme Ebert-Uphoff et al, The outlook for AI weather prediction, Nature (2023). DOI: 10.1038/d41586-023-02084-9

Journal information: Nature

More news stories

Quantum proton billiards: ATLAS experiment reports fundamental properties of strong interactions

The quantum nature of interactions between elementary particles allows drawing non-trivial conclusions even from processes as simple as elastic scattering. The ATLAS experiment at the LHC accelerator reports the measurement ...

GENERAL PHYSICS

JUL 10, 2023

0

10

Scientists use NASA MESSENGER mission data to measure chromium on Mercury

The origin of Mercury, the closest planet to the sun, is mysterious in many ways. It has a metallic core, like Earth, but its core makes up a much larger fraction of its volume—85% compared to 15% for Earth.

PLANETARY SCIENCES

JUL 10, 2023

0

1

New fish species discovered after decades of popularity in the aquarium trade

With just a few clicks of a mouse, you can purchase your very own redtail garra, a type of fish that feeds on algae. Information about the fish's biology, however, is much less easily obtained. That's because redtail garra, ...

PLANTS & ANIMALS

JUL 10, 2023

0

1

New biodegradable plastics are compostable in your backyard

We use plastics in almost every aspect of our lives. These materials are cheap to make and incredibly stable. The problem comes when we're done using something plastic—it can persist in the environment for years. Over time, ...

POLYMERS

JUL 10, 2023

0

0

A new technique uses remote images to gauge the strength of ancient and active rivers beyond Earth

Rivers have flowed on two other worlds in the solar system besides Earth: Mars, where dry tracks and craters are all that's left of ancient rivers and lakes, and Titan, Saturn's largest moon, where rivers of liquid methane ...

PLANETARY SCIENCES

JUL 10, 2023

0

78

Study reveals how a tall spruce develops defense against hungry weevils

A study led by a North Carolina State University researcher identified genes involved in development of stone cells—rigid cells that can block a nibbling insect from eating budding branches of the Sitka spruce evergreen ...

ECOLOGY

JUL 10, 2023

0

1

Caterpillar venom study reveals toxins borrowed from bacteria

Researchers at The University of Queensland have discovered the venom of a notorious caterpillar has a surprising ancestry and could be key to the delivery of lifesaving drugs.

PLANTS & ANIMALS

JUL 10, 2023

0

15

Study reports melting curve of superionic ammonia under icy planetary interior conditions

Icy planets, such as Uranus (U) and Neptune (N), are found in both our solar system and other solar systems across the universe. Nonetheless, these planets, characterized by a thick atmosphere and a mantle made of volatile ...

CONDENSED MATTER

JUL 10, 2023

0

73

Fluorescent tags allow live monitoring of growth factor signaling proteins inside living cells

Synthetic biologists from Rice University and Princeton University have demonstrated "live reporter" technology that can reveal the workings of networks of signaling proteins in living cells with far greater precision than ...

CELL & MICROBIOLOGY

JUL 10, 2023

0

3

Researchers explain how mushrooms can live for hundreds of years without getting cancer

The risk of cancer increases with every cell division. As such, you would expect long-lived species like elephants to get cancer more often than short-lived species like mice. In 1975, however, Richard Peto discovered that ...

PLANTS & ANIMALS

JUL 10, 2023

0

0

Study reveals people most likely to hold antisemitic views

People who believe in conspiracy theories are more likely to have antisemitic opinions than non-believers, new research shows.

SOCIAL SCIENCES

JUL 10, 2023

0

2

Scientists discover 36-million-year geological cycle that drives biodiversity

Movement in the Earth's tectonic plates indirectly triggers bursts of biodiversity in 36‑million-year cycles by forcing sea levels to rise and fall, new research has shown.

EARTH SCIENCES

JUL 10, 2023

0

3

Global cooling caused diversity of species in orchids, confirms study

Research led by the Milner Center for Evolution at the University of Bath looking at the evolution of terrestrial orchid species has found that global cooling of the climate appears to be the major driving factor in their ...

PLANTS & ANIMALS

JUL 10, 2023

0

13

The rise and fall of the Roman empire preserved in pollen

Sediments at the bottom of the ocean can offer a window into the past, indicating environmental conditions not just from the sea but washed in from terrestrial runoff, as well as preserving the flora and fauna of the time. ...

EARTH SCIENCES

JUL 10, 2023

0

59

Bioengineers explore why skin gets 'leathery'

Received wisdom says that staying out in the sun too long can make your skin tougher over time. Think about the "leathery" complexions of farmers, road crews and others who work long hours outdoors, or someone who spends ...

CELL & MICROBIOLOGY

JUL 10, 2023

0

24

These lollipops could 'sweeten' diagnostic testing for kids and adults alike

A lollipop might be a sweet reward for a kid who's endured a trip to the doctor's office, but now, this candy could make diagnostic testing during a visit less invasive and more enjoyable. Researchers publishing in Analytical ...

ANALYTICAL CHEMISTRY

JUL 10, 2023

0

6

New fish species discovered after decades of popularity in the aquarium trade

With just a few clicks of a mouse, you can purchase your very own redtail garra, a type of fish that feeds on algae. Information about the fish's biology, however, is much less easily ...

PLANTS & ANIMALS

JUL 10, 2023

0

1

New biodegradable plastics are compostable in your backyard

We use plastics in almost every aspect of our lives. These materials are cheap to make and incredibly stable. The problem comes when we're done using something plastic—it can persist ...

POLYMERS

JUL 10, 2023

0

0

A new technique uses remote images to gauge the strength of ancient and active rivers beyond Earth

Rivers have flowed on two other worlds in the solar system besides Earth: Mars, where dry tracks and craters are all that's left of ancient rivers and lakes, and Titan, Saturn's largest ...

PLANETARY SCIENCES

JUL 10, 2023

0

78

Study reports melting curve of superionic ammonia under icy planetary interior conditions

Icy planets, such as Uranus (U) and Neptune (N), are found in both our solar system and other solar systems across the universe. Nonetheless, these planets, characterized by a thick atmosphere and a mantle made of volatile ...

Research group unveils properties of cosmic-ray sulfur and the composition of other primary cosmic rays

Charged cosmic rays, high-energy clusters of particles moving through space, were first described in 1912 by physicist Victor Hess. Since their discovery, they have been the topic of numerous astrophysics studies aimed at ...

A new technique uses remote images to gauge the strength of ancient and active rivers beyond Earth

Rivers have flowed on two other worlds in the solar system besides Earth: Mars, where dry tracks and craters are all that's left of ancient rivers and lakes, and Titan, Saturn's largest moon, where rivers of liquid methane ...

PLANETARY SCIENCES

JUL 10, 2023

0

78

Caterpillar venom study reveals toxins borrowed from bacteria

Researchers at The University of Queensland have discovered the venom of a notorious caterpillar has a surprising ancestry and could be key to the delivery of lifesaving drugs.

PLANTS & ANIMALS

JUL 10, 2023

0

15

The rise and fall of the Roman empire preserved in pollen

Sediments at the bottom of the ocean can offer a window into the past, indicating environmental conditions not just from the sea but washed in from terrestrial runoff, as well as preserving the flora and fauna of the time. ...

Observations shed more light on the properties of the galaxy Markarian 817

Using NASA's Swift spacecraft, an international team of astronomers has carried out a long-term multiwavelength monitoring of a nearby active galaxy known as Markarian 817. Results of the observational campaign, published ...

Developing a human malaria-on-a-chip disease model

In a new report published on Scientific Reports, Michael J. Rupar, and a research team at Hesperos Inc., Florida, U.S., developed a functional, multi-organ, serum-free system to culture P. falciparum—a protozoan that predominantly ...

New insight into how plant cells divide

Every time a stem cell divides, one daughter cell remains a stem cell while the other takes off on its own developmental journey. But both daughter cells require specific and different cellular materials to fulfill their ...

PLANTS & ANIMALS

JUL 6, 2023

0

158

How one of nature's most fundamental molecules forms

Life runs on ribosomes. Every cell on Earth needs ribosomes to translate genetic information into all the proteins needed for the organism to function—and to in turn make more ribosomes. But scientists still lack a clear ...

CELL & MICROBIOLOGY

JUL 6, 2023

0

336

Why does matter exist? Roundness of electrons may hold clues

In the first moments of our universe, countless numbers of protons, neutrons and electrons formed alongside their antimatter counterparts. As the universe expanded and cooled, almost all these matter and antimatter particles ...

GENERAL PHYSICS

JUL 6, 2023

31

1882

No comments:

Post a Comment