A Volunteer Army Is Deploying Dirt Cheap Broadband In NYC

from the do-it-yourself dept

A few years ago during one of our Greenhouse forums, activist Terique Boyce wrote about how an all-volunteer army had been spending their days deploying free broadband to NYC residents. It’s the latest example of frustrated communities building their own infrastructure after decades of being ripped off and underserved by powerful, local broadband monopolies.

NYC Mesh is the brainchild of a bunch of ex-Charter (Spectrum) employees who got unceremoniously shitcanned after participating in what was one of the longest ongoing strikes in U.S. history. They funneled their angst into a sort of guerilla activist project that installs wireless mesh networking antennas and routers on the top of buildings to deliver affordable (sometimes free) broadband.

CNET has done a good profile piece on the project, which charges users a $50 fee for the installation and a pay-what-you-can monthly donation to keep the network operating. DIY’ers can install the service for free. Subscribers are encouraged to share their connections with other locals. The organization says it never disconnects users for non-payment.

These aren’t the kind of next-gen fiber connections you want to run a business off of, but they do provide essential access to marginalized neighborhoods that can’t afford broadband from their regional monopoly (in NYC that’s usually Charter/Spectrum or Verizon):

“NYC Mesh is not an internet service provider, but a grassroots, volunteer-run community network. Its aim is to create an affordable, open and reliable network that’s accessible to all New Yorkers for both daily and emergency internet use. Santana says the group’s members want to help people determine their own digital future and “bring back the internet to what it used to be.”

Around a thousand U.S. communities have built some flavor of community-owned and operated broadband network, whether it’s something like NYC Mesh, fiber deployed by the city-owned utility, a local cooperative, or a direct municipal broadband build. As always, these communities wouldn’t be deploying their own networks if not for market failure at the hands of regional monopolies.

“ISPs are always trying to maximize profits. We are just trying to connect our members for the lowest cost possible,” says Brian Hall, one of the lead volunteers and founders of NYC Mesh.

Federal policymakers talk a lot about the “digital divide,” yet routinely fail to address the core reason for it: we turned broadband into a luxury good dominated by a handful of extremely political powerful regional monopolies, hellbent on nickel-and-diming customers trapped by a lack of competition. We didn’t block mergers, we didn’t hold them accountable, and we somehow act surprised at the result.

Instead of directly tackling monopoly power (in fact the folks at the FCC under both parties routinely can’t even admit there’s a problem in public facing statements), we enjoy throwing billions in taxpayer subsidies at said monopolies in the hopes that this time, our “bad luck” will finally change.

Meanwhile, a growing list of communities countrywide have grown tired of waiting for competent federal broadband policy, and continue to take matters into their own hands. Often with zero messaging or policy support from federal regulators purportedly dedicated to “bridging the digital divide.”

Filed Under: broadband, high speed internet, mesh networking, nyc, nycmesh, wireless

____>>

Alternative Broadband Networks: Affordable Internet for the People, One Rooftop at a Time

Volunteer-based organizations like NYC Mesh aim to close the digital divide and build real-life connections.

Before Marco Antonio Santana could speak English, he was speaking computers. Now, the 32-year-old, who grew up in a Dominican household in New York City, helps provide high-speed fiber internet installations and repairs to over 180 units in a low-income housing complex in Manhattan's Lower East Side.

"I've been a nerd my whole life," he tells me, running a delicate strand of fiber-optic cable into a splicer in NYC Mesh's workroom.

We climb to the roof of the 26-story building with striking vistas of the city's water towers, bridges and prewar buildings. There, multiple long-range antennas and routers connect wirelessly to other rooftop nodes as far out as Brooklyn, miles away across the East River. It's one glimpse into the growing network that NYC Mesh has built over the last several years.

NYC Mesh is not an internet service provider, but a grassroots, volunteer-run community network. Its aim is to create an affordable, open and reliable network that's accessible to all New Yorkers for both daily and emergency internet use. Santana says the group's members want to help people determine their own digital future and "bring back the internet to what it used to be."

Internet access is an essential part of our daily lives: for employment, health, education, communication, finances and entertainment. Yet there's a staggering divide between those who can afford to connect and those who can't. At least 42 million Americans are estimated to have no access to high-speed internet, according to the data technology company Broadband Now.

The lack of low-cost, reliable broadband options densely weighs on poor, Black, Latino, indigenous and rural communities. During the COVID-19 pandemic, when being online was the only lifeline, the crisis became even more acute.

"There's a stark problem of access," says Prem Trivedi, policy director at the Open Technology Institute. Students doing homework in a fast-food parking lot to get free Wi-Fi is not sustainable. "That's an intermittent connection that requires upending your life to do bare necessities."

In this article

Digital equity is a herculean mission. It means going up against the few incumbent ISPs — Xfinity, Spectrum, AT&T, Verizon and the like — that determine prices, terms of service, speeds and where infrastructure is built.

"ISPs are always trying to maximize profits. We are just trying to connect our members for the lowest cost possible," says Brian Hall, one of the lead volunteers and founders of NYC Mesh.

Historically, when the private market fails to supply access to a basic good, communities have stepped in to fill in the gaps, according to Sean Gonsalves, associate director for communications at the Institute for Local Self-Reliance. "It's how the electric and telephone cooperatives got started in rural America a century ago."

Providing donation-based internet access is part of NYC Mesh's objective to serve the underserved. The premise is that communication should be free. "We will never disconnect you for payment reasons," says Hall.

NYC Mesh also has public Wi-Fi hotspots across the network. Sharing a wireless connection with neighbors is what security technologist Bruce Schneier once referred to as "basic politeness," akin to providing a hot cup of tea to guests.

Unlike mainstream ISPs, which monitor online activity and sell data to advertisers, NYC Mesh doesn't collect personal data, block content or track users. Hall estimates that thousands of people connect every day to the network across over 1,300 different installations.

NYC Mesh is the largest community-based network in the Americas, and second to the most expansive grassroots mesh network in the world, Guifi, located in Spain. Two decades ago, Guifi started bringing broadband internet to rural Catalonia, and has grown to serve more than 100,000 users. Like NYC Mesh, it's a bottom-up, volunteer-led initiative that's based on common internet infrastructure and cost-sharing.

By publishing extensive documentation on installation procedures, equipment and technical implementation, NYC Mesh offers a blueprint for other community broadband projects. Its website is a treasure trove of open-source materials for groups to replicate and adapt.

Take, for example, Philly Community Wireless, which started establishing much-needed Wi-Fi hotspots in areas around Philadelphia during the pandemic. Now connecting up to 100 active devices daily in conjunction with PhillyWisper, a local independent ISP, Philly Community Wireless also works with local organizations to distribute computers to residents and to install solar power and PurpleAir monitors at community gardens.

The model shows communities how to take control and build out alternative digital ecosystems. "You aren't just a passive consumer of this utility, but an active participant in its construction and sustenance," says Alex Wermer-Colan, the group's executive director.

Growing a mesh metropolis

On a hot afternoon in early August, two NYC Mesh volunteers adjust a newly mounted router on the roof of a four-story brownstone in Park Slope, Brooklyn. There's a direct line of sight to another node half a kilometer away, so the path for transmitting signals between the two wireless antennas is clear. Quincy Blake, the lead installer bearing a backpack and a wispy ponytail, tests the signal strength on his phone, then moves the router another couple of centimeters until he finds the sweet spot.

Within an hour, a cable drops down from the roof to connect with the home router in Willard Nilges' apartment. Nilges, a programmer by day, now has about double the upload speed they had with Spectrum for a fraction of the cost.

Dan Miller, Quincy Blake and Willard Nilges adjust a router on a Brooklyn rooftop. New members can join the NYC Mesh network if there is a clear line of sight from their building to an active node or access point.

Nilges has since become a devoted volunteer for the group, doing installations and writing code. "NYC Mesh is a community. It's neighbors looking out for each other," they tell me via the group's online Slack workspace.

A mesh network is a system of multiple nodes and hubs, also known as access points, that talk to each other via signals from long-range wireless routers and antennas mounted on rooftops. NYC Mesh also has "supernodes" with sector-wide antennas and a fast connection gateway to the internet, often through fiber in the ground. The more devices transmitting data, the further the network can spread.

The concept of meshing is basic to the internet, which started in the late 1960s with four host computer networks and has since grown to billions of devices worldwide. Like a local mesh network, the internet is an intricate web-like structure, where information travels from one point to the next until reaching its destination.

Because mesh networks are decentralized, there's no single point of failure, and users can find a reliable connection in an emergency situation. If one node is blocked or loses signal, the network automatically finds the most direct available path to send data. "The network is self-healing," says Dan Miller, an NYC Mesh volunteer. Miller, who works as a computer engineer at an aerospace company, built a mesh hub on his roof and unlocked an entire dead zone to connect residents and businesses in Bushwick, Brooklyn.

To a layperson like myself, the wireless mesh network resembles the NYC subway, a circuitry of stations and routes. Building nodes are the stations connecting to street level, and neighborhood hubs act as the transfer stations, where you can reroute to several different subway lines. Some routes are faster than others, and sometimes inclement weather and aging infrastructure get in the way.

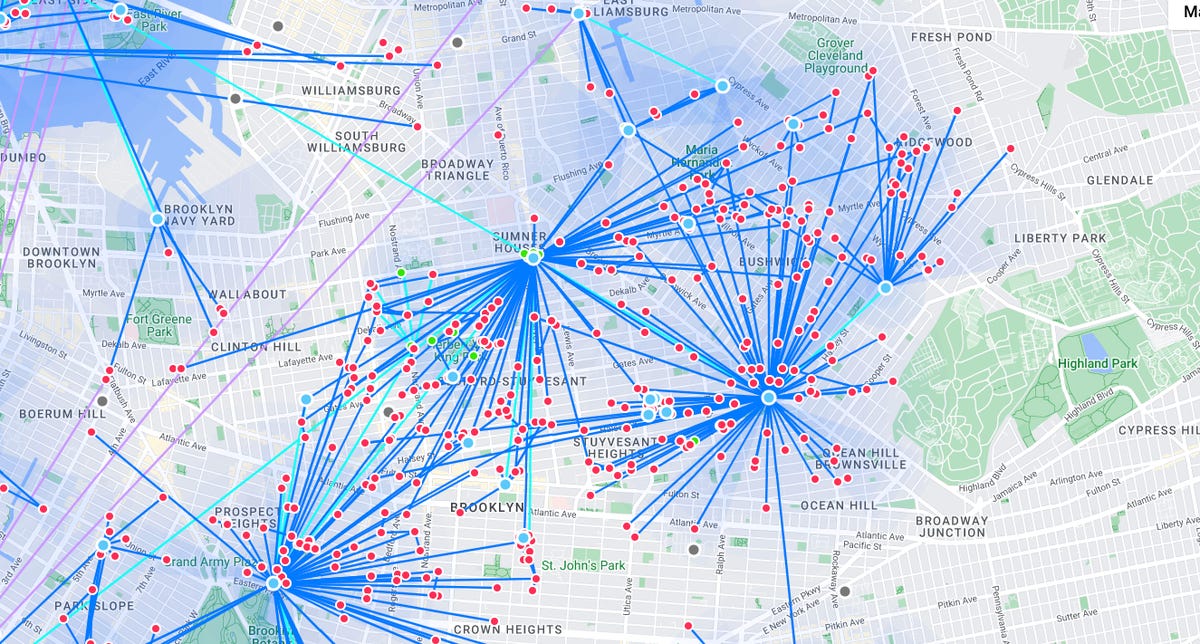

Section of the NYC Mesh map in northwest Brooklyn. The interactive online map shows network coverage around the city in the blue-shaded areas. If you live close to a red dot (a neighbor's node with an omnidirectional antenna), or if you have "line of sight" to any of the blue dots (a primary hub), you can get connected. NYC Mesh will often connect multiple apartments at a single address or an entire residential building.

Wireless mesh networks rely on line-of-sight connections, which is challenging in a city with a jagged skyline, especially if you lack access to the tallest buildings. Though NYC Mesh delivers signals strong enough for most residential use, rooftop wireless routers are susceptible to interference from rain and wind.

The group is actively trying to set up more fiber-line connections, which provide faster download speeds and greater bandwidth than Wi-Fi. Though fiber-optic infrastructure has a much higher upfront installation cost, it's more reliable for broadband connectivity over the long term, offering superior performance to legacy infrastructure.

Sharing a neighborhood connection

ISPs like Verizon and AT&T charge customers for data traffic, affixing high prices to rent their equipment and cables. NYC Mesh legally bypasses the commercial ISPs and gets direct access to the internet through a process called peering, when networks connect and mutually share traffic without charge via internet exchange points.

Flyer created by NYC Mesh member to help with neighborhood outreach.

As for cost, new NYC Mesh users purchase the equipment, and the group asks for a one-time $50 fee for the installation and a pay-what-you-can monthly donation to keep the network operating. Hard-core techies often opt for a DIY ("do it yourself") install, and users request troubleshooting or assistance through the Slack app. "If you have problems, you can message someone and they'll fix it that day if they can," Blake tells me.

Anyone is free to join, as long as they keep the network open and extend it to others. Signing up is done through a simple online form, followed by submitting a panoramic rooftop view to see if there's a clear line of sight to a neighbor's node or hub.

The "share with your neighbor" spirit makes community-building a central element of any mesh network. NYC Mesh doesn't have a hierarchy, though there is a core group of around two dozen active installers and administrators. Everyone who buys a router and connects to the network is a member, not a customer. When asked how the group is structured, a typical response is, "alphabetically."

Volunteers can come and go as they please. The monthly meetups often have a handful who are "fresh to the mesh," and there's talk of needing volunteers and publicity to expand to more neighborhoods and boroughs. "It's all about planting 1,000 seeds and seeing what happens," said Rob Johnson, a lead installer, during a June presentation on boosting mesh infrastructure in Harlem.

NYC Mesh member Andrew Dickinson on the Grand St. Guild building roof in lower Manhattan, where he adjusts the alignment of the antenna connecting to Brooklyn to boost signal strength and rain resilience.

There are numerous ways to get involved, from crimping wires to outreach, and no technical experience is required. Volunteers learn in the wild how networks run, how cables work, how devices are configured. That hands-on engagement is one way NYC Mesh demystifies the internet.

No comments:

Post a Comment