Locus of control has been implicated as playing an important role in a variety of areas in people’s lives, including their health, general well-being and happiness, satisfaction with their jobs and lives overall, and (to some extent) their careers and vocational aspirations and choices.

The Social Learning Theory of

Julian B. Rotter

(1916 - 2014)

Biographical Note

Julian B. Rotter was born in October 1916 in Brooklyn, NY, the third son of Jewish immigrant parents. Rotter's father ran a successful business until the Great Depression. The Depression powerfully influenced Rotter to be aware of social injustice and the effects of the situational environment on people. Rotter's interest in psychology began when he was in high school and read books by Freud and Adler. Rotter attended Brooklyn College, where he began attending seminars given by Adler and meetings of his Society of Individual Psychology in Adler's home.After graduation, Rotter attended the University of Iowa, where he took classes with Kurt Lewin. Rotter minored in speech pathology and studied with the semanticist Wendell Johnson, whose ideas had an enduring influence on Rotter's thinking about the use and misuse of language in psychological science. Upon finishing his master's degree, Rotter took an internship in clinical psychology -- one of the few available at the time -- at Worcester State Hospital in Massachusetts. In 1939, Rotter started his Ph.D. work at Indiana University, one of the few programs to offer a doctorate in clinical psychology. There, he completed his dissertation on level of aspiration and graduated in 1941. By earning his Ph.D. in clinical psychology after having done a predoctoral internship, Rotter became one of the very first clinical psychologists trained in what is now the traditional mode.

After service in the Army and Air Force during World War II, Rotter took an academic position at Ohio State University. It was here that he embarked on his major accomplishment, social learning theory, which integrated learning theory with personality theory. He published Social Learning and Clinical Psychology in 1954. Rotter also held strong beliefs about how clinical psychologists should be educated. He was an active participant in the 1949 Boulder Conference, which defined the training model for doctoral level clinical psychologists. He spoke persuasively that psychologists must be trained in psychology departments, not under the supervision of psychiatrists. His ideas are still influential today (Herbert, 2002).

In 1963, Rotter left Ohio State to become the director of the clinical psychology training program at the University of Connecticut. After his retirement, he remained professor emeritus there.

Rotter served as president of the American Psychological Association's divisions of Social and Personality Psychology and Clinical Psychology. In 1989, he was given the American Psychological Association's Distinguished Scientific Contribution award.

Rotter was married to Clara Barnes, whom he had met at Worcester State, from 1941 until her death in 1985. They had two children. He later married psychologist Dorothy Hochreich. Rotter died January 6, 2014, at the age of 97 at his home in Connecticut.

[The above information is based on a biographical essay written by Julian Rotter: Rotter, J. B. (1993). Expectancies. In C. E. Walker (Ed.), The history of clinical psychology in autobiography (vol. II) (pp. 273-284). Pacific Grove, CA: Brooks/Cole. Photos courtesy of University of Connecticut.]

BASIC INFORMATION from Wikipedia

Reference: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Locus_of_control

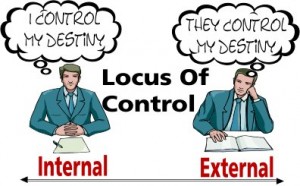

Locus of control is the degree to which people believe that they, as opposed to external forces (beyond their influence), have control over the outcome of events in their lives. The concept was developed by Julian B. Rotter in 1954, and has since become an aspect of personality psychology. A person's "locus" (plural "loci", Latin for "place" or "location") is conceptualized as internal (a belief that one can control one's own life) or external (a belief that life is controlled by outside factors which the person cannot influence, or that chance or fate controls their lives).[1]

Individuals with a strong internal locus of control believe events in their life are primarily a result of their own actions: for example, when receiving exam results, people with an internal locus of control tend to praise or blame themselves and their abilities. People with a strong external locus of control tend to praise or blame external factors such as the teacher or the exam.[2]

Locus of control has generated much research in a variety of areas in psychology. The construct is applicable to such fields as educational psychology, health psychology, industrial and organizational psychology, and clinical psychology. Debate continues whether domain-specific or more global measures of locus of control will prove to be more useful in practical application. Careful distinctions should also be made between locus of control (a personality variable linked with generalized expectancies about the future) and attributional style (a concept concerning explanations for past outcomes), or between locus of control and concepts such as self-efficacy.

Locus of control is one of the four dimensions of core self-evaluations – one's fundamental appraisal of oneself – along with neuroticism, self-efficacy, and self-esteem.[3] The concept of core self-evaluations was first examined by Judge, Locke, and Durham (1997), and since has proven to have the ability to predict several work outcomes, specifically, job satisfaction and job performance.[4] In a follow-up study, Judge et al. (2002) argued that locus of control, neuroticism, self-efficacy, and self-esteem factors may have a common core.[5]

KEEP IN MIND: Regarding locus of control, there is another type of control that entails a mix among the internal and external types.

People that have the combination of the two types of locus of control are often referred to as Bi-locals. People that have Bi-local characteristics are known to handle stress and cope with their diseases more efficiently by having the mixture of internal and external locus of control.[9] People that have this mix of loci of control can take personal responsibility for their actions and the consequences thereof while remaining capable of relying upon and having faith in outside resources; these characteristics correspond to the internal and external loci of control, respectively.

KEEP IN MIND: Rotter (1975) cautioned that internality and externality represent two ends of a continuum, not an either/or typology.

Internals tend to attribute outcomes of events to their own control. People who have internal locus of control believe that the outcomes of their actions are results of their own abilities. Internals believe that their hard work would lead them to obtain positive outcomes.[8] They also believe that every action has its consequence, which makes them accept the fact that things happen and it depends on them if they want to have control over it or not. Externals attribute outcomes of events to external circumstances.

Externals, with an external locus of control tend to believe that the things which happen in their lives are out of their control,[9] and even that their own actions are a result of external factors, such as fate, luck, the influence of powerful others (such as doctors, the police, or government officials) and/or a belief that the world is too complex for one to predict or successfully control its outcomes. Such people tend to blame others rather than themselves for their lives' outcomes. It should not be thought, however, that internality is linked exclusively with attribution to effort and externality with attribution to luck (as Weiner's work – see below – makes clear).

This has obvious implications for differences between internals and externals in terms of their achievement motivation, suggesting that internal locus is linked with higher levels of need for achievement. Due to their locating control outside themselves, externals tend to feel they have less control over their fate. People with an external locus of control tend to be more stressed and prone to clinical depression.[10]

Stress[edit]

The previous section showed how self-efficacy can be related to a person's locus of control, and stress also has a relationship in these areas. Self-efficacy can be something that people use to deal with the stress that they are faced within their everyday lives. Some findings suggest that higher levels of external locus of control combined with lower levels self-efficacy are related to higher illness-related psychological distress.[74] People who report a more external locus of control also report more concurrent and future stressful experiences and higher levels of psychological and physical problems.[55] These people are also more vulnerable to external influences and as a result, they become more responsive to stress.[74]

Veterans of the military forces who have spinal cord injuries and post-traumatic stress are a good group to look at in regard to locus of control and stress. Aging shows to be a very important factor that can be related to the severity of the symptoms of PTSD experienced by patients following the trauma of war.[76] Research suggests that patients with a spinal cord injury benefit from knowing that they have control over their health problems and their disability, which reflects the characteristics of having an internal locus of control . . .

Organizational psychology and religion[edit]

Other fields to which the concept has been applied include industrial and organizational psychology, sports psychology, educational psychology and the psychology of religion. Richard Kahoe has published work in the latter field, suggesting that intrinsic religious orientation correlates positively (and extrinsic religious orientation correlates negatively) with internal locus.[38] Of relevance to both health psychology and the psychology of religion is the work of Holt, Clark, Kreuter and Rubio (2003) on a questionnaire to assess spiritual-health locus of control. The authors distinguished between an active spiritual-health locus of control (in which "God empowers the individual to take healthy actions"[39]) and a more passive spiritual-health locus of control (where health is left up to God). In industrial and organizational psychology, it has been found that internals are more likely to take positive action to change their jobs (rather than merely talk about occupational change) than externals.[40][33] Locus of control relates to a wide variety of work variables, with work-specific measures relating more strongly than general measures.[41] In Educational setting, some research has shown that students who were intrinsically motivated had processed reading material more deeply and had better academic performance than students with extrinsic motivation.[42]

Consumer research[edit]

Locus of control has also been applied to the field of consumer research. For example, Martin, Veer and Pervan (2007) examined how the weight locus of control of women (i.e., beliefs about the control of body weight) influence how they react to female models in advertising of different body shapes. They found that women who believe they can control their weight ("internals"), respond most favorably to slim models in advertising, and this favorable response is mediated by self-referencing. In contrast, women who feel powerless about their weight ("externals"), self-reference larger-sized models, but only prefer larger-sized models when the advertisement is for a non-fattening product. For fattening products, they exhibit a similar preference for larger-sized models and slim models. The weight locus of control measure was also found to be correlated with measures for weight control beliefs and willpower.[43]

Political ideology[edit]

Locus of control has been linked to political ideology. In the 1972 U.S. presidential election, research of college students found that those with an internal locus of control were substantially more likely to register as a Republican, while those with an external locus of control were substantially more likely to register as a Democratic.[44] A 2011 study surveying students at Cameron University in Oklahoma found similar results,[45] although these studies were limited in scope. Consistent with these findings, Kaye Sweetser (2014) found that Republicans significantly displayed greater internal locus of control than Democrats and Independents.[46]

Those with an internal locus of control are more likely to be of higher socioeconomic status, and are more likely to be politically involved (e.g., following political news, joining a political organization)[47] Those with an internal locus of control are also more likely to vote.[48][49]

Familial origins[edit]

The development of locus of control is associated with family style and resources, cultural stability and experiences with effort leading to reward.[citation needed] Many internals have grown up with families modeling typical internal beliefs; these families emphasized effort, education, responsibility and thinking, and parents typically gave their children rewards they had promised them. In contrast, externals are typically associated with lower socioeconomic status. Societies experiencing social unrest increase the expectancy of being out-of-control; therefore, people in such societies become more external.[50]

The 1995 research of Schneewind suggests that "children in large single parent families headed by women are more likely to develop an external locus of control"[51][52] Schultz and Schultz also claim that children in families where parents have been supportive and consistent in discipline develop internal locus of control. At least one study has found that children whose parents had an external locus of control are more likely to attribute their successes and failures to external causes.[53] Findings from early studies on the familial origins of locus of control were summarized by Lefcourt: "Warmth, supportiveness and parental encouragement seem to be essential for development of an internal locus".[54] However, causal evidence regarding how parental locus of control influences offspring locus of control (whether genetic, or environmentally mediated) is lacking.

Locus of control becomes more internal with age. As children grow older, they gain skills which give them more control over their environment. However, whether this or biological development is responsible for changes in locus is unclear.[50]

Age[edit]

Some studies showed that with age people develop a more internal locus of control,[55] but other study results have been ambiguous.[56][57] Longitudinal data collected by Gatz and Karel imply that internality may increase until middle age, decreasing thereafter.[58] Noting the ambiguity of data in this area, Aldwin and Gilmer (2004) cite Lachman's claim that locus of control is ambiguous. Indeed, there is evidence here that changes in locus of control in later life relate more visibly to increased externality (rather than reduced internality) if the two concepts are taken to be orthogonal. Evidence cited by Schultz and Schultz (2005) suggests that locus of control increases in internality until middle age. The authors also note that attempts to control the environment become more pronounced between ages eight and fourteen.[59][60]

Health locus of control is how people measure and understand how people relate their health to their behavior, health status and how long it may take to recover from a disease.[9] Locus of control can influence how people think and react towards their health and health decisions. Each day we are exposed to potential diseases that may affect our health. The way we approach that reality has a lot to do with our locus of control. Sometimes it is expected to see older adults experience progressive declines in their health, for this reason it is believed that their health locus of control will be affected.[9] However, this does not necessarily mean that their locus of control will be affected negatively but older adults may experience decline in their health and this can show lower levels of internal locus of control.

Age plays an important role in one's internal and external locus of control. When comparing a young child and an older adult with their levels of locus of control in regards to health, the older person will have more control over their attitude and approach to the situation. As people age they become aware of the fact that events outside of their own control happen and that other individuals can have control of their health outcomes.[9]

A study published in the journal Psychosomatic Medicine examined the health effect of childhood locus of control. 7,500 British adults (followed from birth), who had shown an internal locus of control at age 10, were less likely to be overweight at age 30. The children who had an internal locus of control also appeared to have higher levels of self-esteem.[61]

Cross-cultural and regional issues[edit]

The question of whether people from different cultures vary in locus of control has long been of interest to social psychologists.

Japanese people tend to be more external in locus-of-control orientation than people in the U.S.; however, differences in locus of control between different countries within Europe (and between the U.S. and Europe) tend to be small.[67] As Berry et al. pointed out in 1992, ethnic groups within the United States have been compared on locus of control; African Americans in the U.S. are more external than whites when socioeconomic status is controlled.[68][67] Berry et al. also pointed out in 1992 how research on other ethnic minorities in the U.S. (such as Hispanics) has been ambiguous. More on cross-cultural variations in locus of control can be found in Shiraev & Levy (2004). Research in this area indicates that locus of control has been a useful concept for researchers in cross-cultural psychology.

On a less broad scale, Sims and Baumann explained how regions in the United States cope with natural disasters differently. The example they used was tornados. They "applied Rotter's theory to explain why more people have died in tornado[e]s in Alabama than in Illinois".[37] They explain that after giving surveys to residents of four counties in both Alabama and Illinois, Alabama residents were shown to be more external in their way of thinking about events that occur in their lives. Illinois residents, however, were more internal. Because Alabama residents had a more external way of processing information, they took fewer precautions prior to the appearance of a tornado. Those in Illinois, however, were more prepared, thus leading to fewer casualties.[69]

No comments:

Post a Comment