To anyone reading this who is worried that this is just another brick in the wall of AI privacy issues, fear not. The encoding system is incredibly personalized to each individual participant and requires a host of invasive electrodes and training in order for it to create a rough approximation of the song they were listening to. There’s no need to fear machines reading your mind and listening to the music you’re thinking about.

Instead, this technology holds a lot of promise for brain-computer interfaces that could allow those who are paralyzed, have neurological issues, or can’t speak to be able to create and perceive music on their own. While companies like Neuralink and Synchron are hard at work creating BCIs to allow for speech and interactions with computers and mobile devices (not to mention games of pong), there’s been little effort done in the way of music. This sort of development could help give greater accessibility to those conditions that impair their motor functions.

If nothing else, it shows us that, ironically, we do need a little thought control.

AI Recreated a Pink Floyd Song with Brain Scans—and It Sounds Creepy

Think of your favorite song right now and play it in your head. You might find yourself nodding along or tapping your fingers to the beat—but that experience is fairly personal. No one else around can hear what you’re hearing. This is a concert just for you.

But, with the power of AI, that might all soon change. A team of researchers at the University of California, Berkeley published a study Tuesday in the journal PLOS Biology where they developed a machine learning model that could decode brain activity to recreate the Pink Floyd classic “Another Brick in the Wall, Part 1.” The system could be used for future brain-computer interface (BCI) technologies to recreate the qualities of music using the mind.

“We reconstructed the classic Pink Floyd song “Another Brick in the Wall” from direct human cortical recordings, providing insights into the neural bases of music perception and into future brain decoding applications,” Ludovic Bellier, a computational research scientist at UC Berkeley, said in a press release.

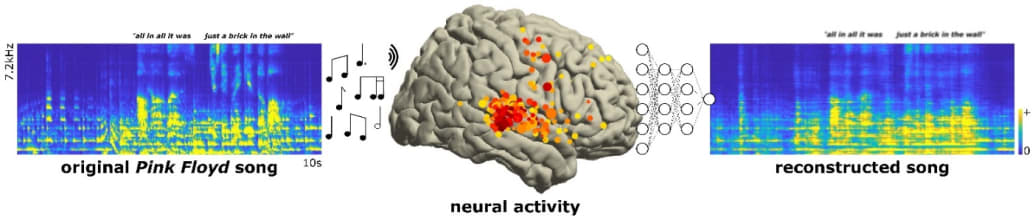

The neural activity of 29 intracranial patients (middle panel) listening to the classic Pink Floyd song "Another Brick in the Wall, Part 1" (left panel, excerpt of the original song spectrogram). Using nonlinear models, the team successfully reconstructed a recognizable song from these direct cortical recordings (right panel, reconstructed spectrogram).

Ludovic Bellier, PhD

The study builds on previous research from a team of neuroscientists at the University of Texas at Austin who built a brain decoder that could reconstruct people’s thoughts based on fMRI scans. Realizing that there was also a need for a model that could recreate musical elements such as pitch, melody, and rhythm, the UC Berkeley team set out to create a brain decoder for music.

To accomplish this, the researchers attached 2,668 intracranial electroencephalography (iEEG) electrodes to the brains of 29 patients as they listened to “Another Brick in the Wall.” They discovered that electrodes placed specifically at the Superior Temporal Gyrus (STG) region of the brain were largely responsible for auditory processing and rhythm perception—and provided the best data for reconstructing the music.

The results were stunning. The team was able to roughly recreate the song into an eerie approximation. They also found that the more electrode data that was fed into the model, the more accurate the song could be reconstructed.

The team also moved around electrodes and played around with what kind of data was collected from what parts of the brain in order to create different reconstructions of the song. This allowed them to find out which regions of the brain and parts of a song were most important for reconstruction. They discovered that the right STG was vital to the system. Removing the electrodes associated with rhythm also caused the reconstruction to be shoddier.

“Combining unique iEEG data and modeling-based analysis, we provided the first recognizable song reconstructed from direct brain recordings,” the authors wrote. “We showed the feasibility of applying predictive modeling on a relatively short dataset, in a single patient, and quantified the impact of different methodological factors on the prediction accuracy of decoding models.”

The authors note that future research could involve adding more electrodes to cover even more regions of the brain. They also said that they didn’t have data on how familiar the patients were with the song or music in general—which could impact outcomes from person to person.

No comments:

Post a Comment