Probabilistic weather forecasting with machine learning

Nature (2024)

Abstract

Weather forecasts are fundamentally uncertain, so predicting the range of probable weather scenarios is crucial for important decisions, from warning the public about hazardous weather to planning renewable energy use. Traditionally, weather forecasts have been based on numerical weather prediction (NWP)1, which relies on physics-based simulations of the atmosphere. Recent advances in machine learning (ML)-based weather prediction (MLWP) have produced ML-based models with less forecast error than single NWP simulations2,3. However, these advances have focused primarily on single, deterministic forecasts that fail to represent uncertainty and estimate risk. Overall, MLWP has remained less accurate and reliable than state-of-the-art NWP ensemble forecasts. Here we introduce GenCast, a probabilistic weather model with greater skill and speed than the top operational medium-range weather forecast in the world, ENS, the ensemble forecast of the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts4. GenCast is an ML weather prediction method, trained on decades of reanalysis data. GenCast generates an ensemble of stochastic 15-day global forecasts, at 12-h steps and 0.25° latitude–longitude resolution, for more than 80 surface and atmospheric variables, in 8 min. It has greater skill than ENS on 97.2% of 1,320 targets we evaluated and better predicts extreme weather, tropical cyclone tracks and wind power production. This work helps open the next chapter in operational weather forecasting, in which crucial weather-dependent decisions are made more accurately and efficiently.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Every day, people, governments and other organizations around the world rely on accurate weather forecasts to make many key decisions—whether to carry an umbrella, when to flee an approaching tropical cyclone, how to plan the use of renewable energy in a power grid, or how to prepare for a heatwave. But forecasts will always have some uncertainty, because we can only partially observe the current weather, and even our best weather models are imperfect. The highly non-linear physics of weather means that small initial uncertainties and errors can rapidly grow into large uncertainties about the future5. Making important decisions often requires knowing not just a single probable scenario but the range of possible scenarios and how likely they are to occur.

Traditional weather forecasting is based on numerical weather prediction (NWP) algorithms, which approximately solve the equations that model atmospheric dynamics. Deterministic NWP methods map the current estimate of the weather to a forecast of how the future weather will unfold over time. To model the probability distribution of different future weather scenarios6,7, weather agencies increasingly rely on ensemble forecasts, which generate several NWP-based forecasts, each of which models a single possible scenario4,8,9,10,11. ENS of the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasting (ECMWF)4 is the state-of-the-art NWP-based ensemble forecast in the broader Integrated Forecast System of the ECMWF and will subsume their deterministic forecast, HRES, going forward12.

ENS satisfies several key desiderata of a probabilistic weather model. First, its ensemble members represent sharp and spectrally realistic individual weather trajectories, as opposed to some summary statistic such as a conditional mean. Second, it produces skilful and calibrated marginal forecast distributions (forecasts of the weather at a given place and time), which is important for many day-to-day users of weather forecasts. Third, it captures the aspects of the joint spatiotemporal structure of the forecast distribution that are crucial for probabilistic modelling of large-scale phenomena such as cyclones and for applications such as forecasting distributed energy generation. Nonetheless, ENS—along with other NWP-based ensemble forecasts—is still prone to errors, is slow to run and is time-consuming to engineer.

Recent advances in machine learning (ML)-based weather prediction (MLWP) have been shown to provide greater accuracy and efficiency than NWP for non-probabilistic forecasts2,3,13,14,15,16,17,18. Rather than forecasting a single weather trajectory, or a distribution of trajectories, these methods have largely focused on forecasting the mean of the probable trajectories, with relatively little emphasis on quantifying the uncertainty associated with a forecast. They are typically trained to minimize the mean squared error (MSE) of their predictions and as a result tend to produce blurry forecasts, especially at longer lead times, rather than a specific realization of a possible weather state2. There have been limited attempts to use traditional initial condition perturbation methods to produce ensembles with MLWP-based forecasts3,15,18,19. However, these methods have not addressed the issue of blurring—meaning that their ensemble members do not represent realistic samples from the weather distribution—and they have not rivalled operational ensemble forecasts such as ENS. An exception is NeuralGCM20, a hybrid NWP–MLWP method, which combines the dynamical core of a traditional NWP with local ML-based parameterizations and shows competitive performance with operational ensemble forecasts. However, ensembles of this hybrid model have 1.4° spatial resolution, which is an order of magnitude coarser than operational NWP-based forecasts.

This work presents GenCast, the first MLWP method, to our knowledge, that significantly outperforms the top operational ensemble NWP model, ENS. We demonstrate that GenCast generates ensembles of realistic individual weather trajectories, providing both better marginal and better joint forecast distributions than ENS.

GenCast

GenCast is a probabilistic weather model that generates global 15-day ensemble forecasts at 0.25° resolution, which are more accurate than the top operational ensemble system, ENS of ECMWF. Generating a single 15-day GenCast forecast takes about 8 min on a Cloud TPUv5 device, and an ensemble of forecasts can be generated in parallel.

GenCast models the conditional probability distribution P(Xt+1|Xt, Xt−1) of the future weather state Xt+1 conditional on the current and previous weather states. A forecast trajectory X1:T of length T is modelled by conditioning on the initial and previous states, (X0, X−1), and factoring the joint distribution over successive states,

each of which is sampled autoregressively.

The representation of the global weather state, X, consists of six surface variables and six atmospheric variables at 13 vertical pressure levels (Extended Data Table 1) on an equiangular 0.25° latitude–longitude grid. The forecast horizon is 15 days, with 12 h between successive steps t and t + 1, so T = 30. We train GenCast using analysis for X, which represents the best estimate of the weather state, inferred from observations.

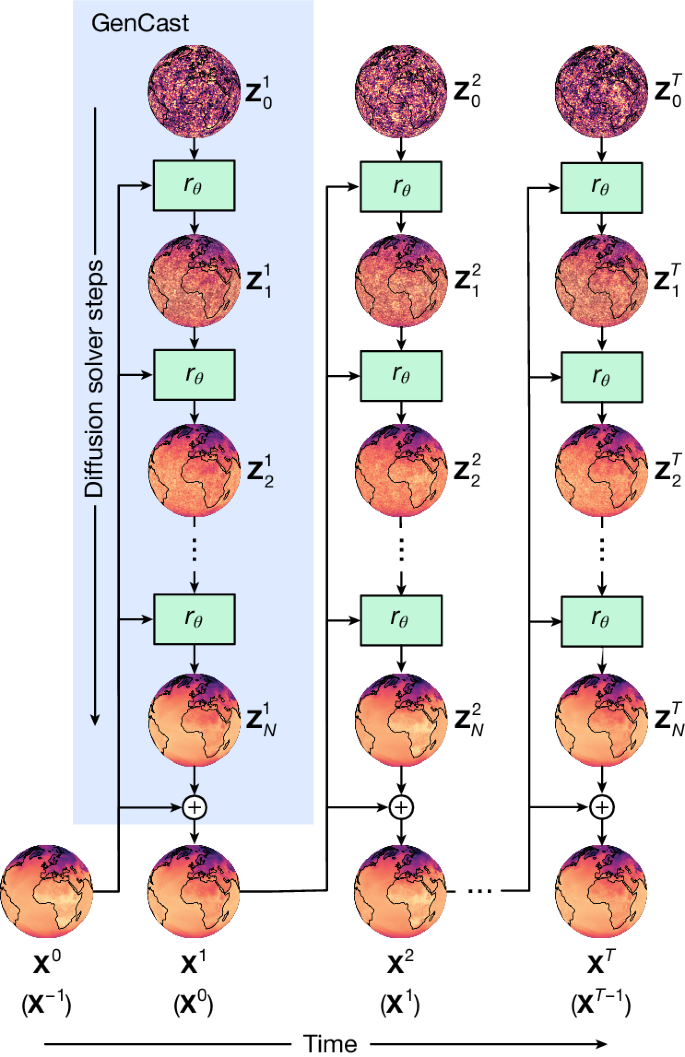

GenCast is implemented as a conditional diffusion model21,22,23, a generative ML method that can model the probability distribution of complex data and generate new samples. Diffusion models underpin many of the recent advances in modelling natural images, sounds and videos under the umbrella of generative AI24,25. Diffusion models work through a process of iterative refinement. A future atmospheric state, Xt+1, is produced by iteratively refining a candidate state initialized as pure noise, , conditioned on the previous two atmospheric states (Xt, Xt−1). The blue box in Fig. 1 shows how the first forecast step is generated from the initial conditions and how the full trajectory, X1:T, is generated autoregressively. Because each time step in a forecast is initialized with noise (), the process can be repeated with different noise samples to generate an ensemble of trajectories. See Methods for further details of the sampling process.

The blue box shows how, conditioning on inputs (X0, X−1), an initial noise sample, , is refined by the neural network refinement function, rθ (green box), which is parameterized by θ. The resulting is the first refined candidate state, and this process repeats N times. The final is then added as a residual to X0 to produce the weather state at the next time step, X1. This process then repeats autoregressively, T = 30 times, conditioning on (Xt, Xt−1) and using a new initial noise sample at each step to produce the full weather trajectory sample (for visual clarity, we illustrate the previous state in parentheses, (Xt−1), below the current state, Xt, but note that it is not added to as a residual for predicting Xt+1). Each trajectory generated by independent noise samples represents a sample from, P(X1:T|X0, X−1).

At each stage of the iterative refinement process, GenCast makes use of a denoiser neural network, which is trained to remove noise artificially added to atmospheric states using the loss function described in the Methods. The architecture of the denoiser comprises an encoder, processor and decoder. The encoder component maps a noisy target state , as well as the conditioning (Xt, Xt−1), from the equiangular 0.25° latitude–longitude grid to an internal learned representation defined on a six-times-refined icosahedral mesh. The processor component is a graph transformer26 in which each node attends to its k-hop neighbourhood on the mesh. The decoder component maps from the internal mesh representation back to a denoised target state, defined on the grid.

GenCast is trained on 40 years of best-estimate analysis from 1979 to 2018, taken from the publicly available ERA5 (fifth generation ECMWF reanalysis) reanalysis dataset27. Reanalysis provides a reconstruction of past weather by computing analysis for historical dates and times. For simplicity, we refer to ERA5 reanalysis as analysis from here on. Full details of the GenCast architecture and training protocol are provided in the Methods. When evaluating GenCast, we initialize it with ERA5 analysis.

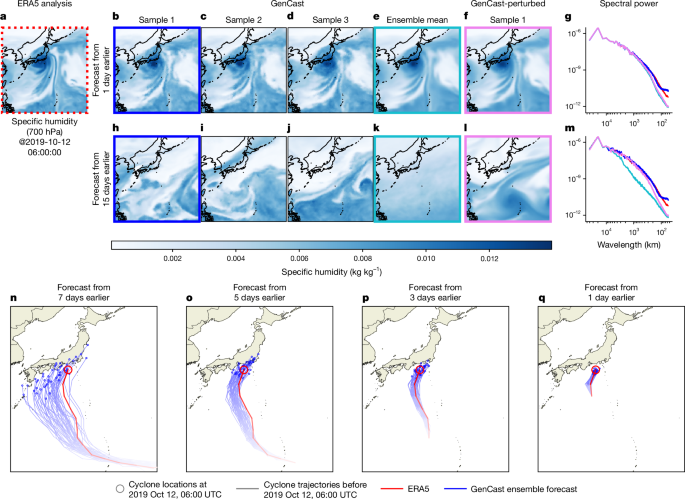

As an illustrative example, Fig. 2b–d,h–j showcases GenCast forecast samples and Fig. 2n–q provides an example of how they can be used in important downstream applications, such as predicting the paths of tropical cyclones. Typhoon Hagibis—the costliest tropical cyclone of 2019—is shown as a representative case study. When initialized 7 days before the landfall of Typhoon Hagibis, the predicted trajectories of GenCast exhibit high uncertainty, covering a wide range of possible scenarios. At shorter lead times, the uncertainty of GenCast about the path of the cyclone is lower, reflecting greater confidence about the landfall timing and location.

a, The ERA5 analysis state27 for specific humidity at 700 hPa, at validity time 06 UTC, 12 October 2019, shows Typhoon Hagibis near the centre of the frame, hours before making landfall in Japan. b–d, Sample 1 (b), sample 2 (c) and sample 3 (d) GenCast forecast states, initialized one day earlier, show how the samples are sharp and very similar to one another. e, The GenCast ensemble mean, obtained by computing the mean of 50 sample states such as in b–d, is somewhat blurry, showing how uncertainty results in a blurrier average state. f, Sample 1 forecast state from GenCast-Perturbed, initialized one day earlier as in b–e, is blurry, similar to a single-step ensemble mean. g, The spatial power spectrum of the states in a, b, e and f, in which the line colours match the frames of the panels, show how spectra of the GenCast samples closely match with that of ERA5, whereas the blurrier GenCast ensemble mean and GenCast-Perturbed states have less power at shorter wavelengths. h–m, These subplots are analogous to b–g, except the forecasts are initialized 15 days earlier. The GenCast samples are still sharp (h–j) and GenCast-Perturbed (l) is still equally blurry, whereas the GenCast ensemble mean (k) is even blurrier than at 1-day lead time. This is also reflected in the power spectrum (m). n–q, The trajectory of Typhoon Hagibis based on ERA527 (in red) and the ensemble of tropical cyclone trajectories from GenCast (in blue) up to a validity time 4 h before the cyclone made landfall in Japan. GenCast forecasts are shown at lead times of 7 days, 3 days, 5 days and 1 day. The blue and red circles show cyclone locations at the validity time. At long lead times, the cyclone trajectories have a substantial spread, whereas for the shorter lead times, the predictive uncertainty collapses to a small range of trajectories. Typhoon Hagibis represents the 55th percentile of GenCast’s ensemble mean position error among tropical cyclones in 2019.

Baselines

We compare GenCast to ENS, currently the best operational ensemble forecast, which we regridded from its (pre-June 2023) native 0.2° latitude–longitude resolution to 0.25°. ENS contains 50 perturbed ensemble members, so we used 50-member GenCast ensembles to perform all evaluations. The public TIGGE archive28 only makes all 50 ENS ensemble members available for surface variables and for atmospheric variables at eight pressure levels in the troposphere. So these are the variables and levels we compare models on.

We also develop a deterministic 12 h step forecast model using the GenCast architecture, to serve as a strong ML baseline and an ablation of the role of diffusion. We used this model to generate ensemble forecasts (denoted as GenCast-Perturbed) by initializing it using ERA5 analysis perturbed by Gaussian Process noise; full details are in Supplementary Information section A.4.

For a fair comparison of models, we evaluate each model against its corresponding best-estimate analysis, following established practice2,29. We thus evaluate the operational forecasts of ECMWF against HRES-fc030 (a dataset comprising the initial conditions used for the HRES deterministic forecast of ECMWF), and we evaluate ML models that were trained and initialized using ERA5, against ERA530.

We use 2019 as our test period, and, following the protocol in ref. 2, we initialize ML models using ERA5 at 06 UTC and 18 UTC, as these benefit from only 3 h of look-ahead (with the exception of sea surface temperature, which in ERA5 is updated once per 24 h). This ensures ML models are not afforded an unfair advantage by initializing from states with longer look-ahead windows.

We follow a standard verification practice29 in evaluating ensemble forecasts using best-estimate analysis as ground truth. However, we note that this does not reward representing initial condition uncertainty. We also note that we evaluate the raw output of GenCast against that of ENS, following standard practice in the field. Both MLWP and NWP forecasts can be further improved by post-processing methods, and the relative impact of these methods on the two approaches is an interesting direction for future work.

Realism of GenCast samples

Figure 2 shows some of the forecast samples of GenCast for Typhoon Hagibis, shortly before it made landfall in Japan on 12 October 2019. Figure 2b–e,g,h–k,m shows that GenCast forecasts are sharp and have spherical harmonic power spectra that closely match the ERA5 ground truth at both 1- and 15-day lead times. This reflects how the ensemble members of GenCast, like those of ENS, represent realistic samples of the weather. As expected, the GenCast ensemble mean is blurry, losing power at high frequencies (see also Supplementary Figs. B5 and B6). Forecasts by deterministic models trained to minimize forecast MSE—including top deterministic MLWP models such as GraphCast2—are blurred and closer to the ensemble mean2. Ensemble members generated by perturbing these deterministic models also blur. This is especially true for multi-step-trained models such as GraphCast, but it is also true (albeit to a lesser extent) for models such as GenCast-Perturbed (Fig. 2f,l), which are only trained to predict a one-step forecast-distribution mean.

Skilful marginal forecast distributions

Many day-to-day users of weather forecasts rely on the spatiotemporal marginals of the forecast distributions, that is, the weather forecast for a given place and time. We evaluate the per-grid-cell marginals of GenCast and ENS in terms of overall forecast skill, calibration and performance on extreme weather prediction.

Ensemble skill

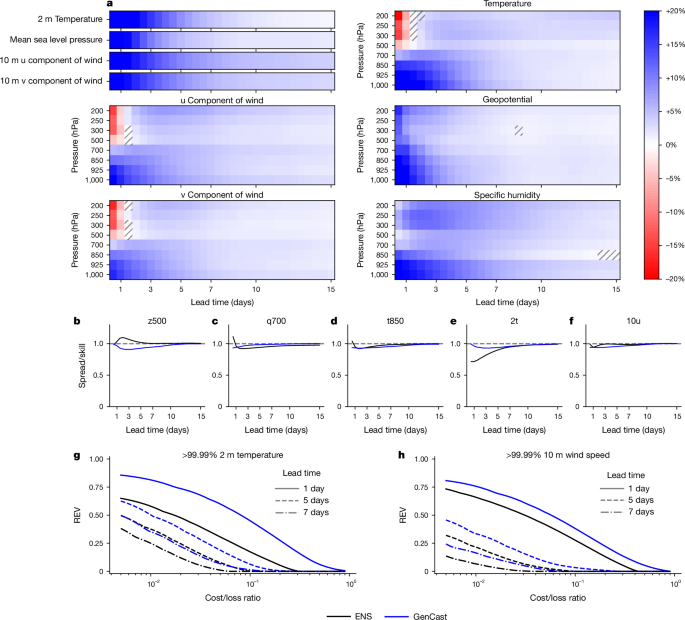

The CRPS31 is a standard measure of the skill of a probabilistic forecast. It measures how well the marginal distributions of the forecast represent the ground truth, and it is minimized, in expectation, by a forecast whose marginals reflect true predictive uncertainty. See Supplementary Information section A.5.1 for the mathematical definition of CRPS. As shown in the scorecard of Fig. 3, the forecasts of GenCast are significantly more skilful (P < 0.05) than that of ENS on 97.2% of our 1,320 variable, lead time and vertical level combinations (and 99.6% of targets at lead times greater than 36 h). Although dependencies across weather variables mean that these 1,320 scorecard targets do not each represent independent forecast tasks, such scorecards are a standard means of summarizing model performance. The largest improvements of GenCast are often at shorter lead times up to around 3–5 days, for surface variables, as well as temperature and specific humidity at higher pressure levels, for which the CRPS skill scores range between 10% and 30% better. GenCast-Perturbed also achieves strong results, with better or competitive CRPS compared with ENS on 82% of scorecard targets (Supplementary Fig. B7) but is still definitively worse than that of GenCast, which outperforms the CRPS of GenCast-Perturbed in 99% of targets (Extended Data Fig. 8 and Supplementary Fig. B8). Owing to our lack of confidence in the quality of ERA5 precipitation data, we exclude precipitation results from our main results and refer readers to Supplementary Information section B.2.

a, CRPS scores for GenCast versus ENS4 in 2019. The scorecard compares CRPS skill between GenCast and ENS across all variables and eight pressure levels. Dark-blue cells on the scorecard indicate a variable, lead time and level combination for which GenCast has 20% better (that is, lower) CRPS than ENS, whereas dark-red cells indicate 20% lower CRPS for ENS (white means they perform equally). The results show that GenCast significantly (P < 0.05) outperforms ENS on 97.2% of all reported variable, lead time and level combinations. Hatched regions indicate neither model is significantly better. b–f, Spread/skill scores for GenCast and ENS for selected variables. Both models are generally well-calibrated with spread/skill close to 1. g,h, REV for predictions of the exceedance of the 99.99th percentile for 2 m temperature and 10 m wind speed, at lead times of 1 day, 5 days and 7 days. GenCast consistently achieves greater REV than ENS whenever either forecast is better than climatology, particularly at small cost/loss ratios.

We also compared the root mean squared error (RMSE) of the ensemble means of GenCast and ENS. The ensemble-mean RMSE measures how closely the mean of an ensemble of forecasts matches ground truth. Although RMSE is a common metric for deterministic forecasts, it does not account for uncertainty, which is central to probabilistic verification. Nonetheless, as shown in Extended Data Fig. 1, the ensemble mean RMSE of GenCast is as good or better than that of ENS on 96% of targets and significantly better (P < 0.05) on 78% of targets.

Ensemble calibration

For a probabilistic forecast to be useful, it should be well-calibrated: it should know when it may be wrong and have confidence when it is likely to be right. This is a crucial aspect of the quality of the forecast distribution, allowing a decision-maker to hedge their choices in proportion to the confidence of the forecast. Two common tools in the weather community for evaluating calibration of the marginal forecast distributions, on average, are spread/skill ratios and rank histograms.

Well-calibrated probabilistic forecasts exhibit uncertainty (as measured by ensemble spread), which is commensurate on average with the size of their errors32. The degree to which this relationship holds can be quantified by the spread/skill ratio defined in Supplementary Information section A.5.3. This ratio should be 1 for a perfect ensemble forecast, with values greater than 1 suggestive of overdispersion (an underconfident forecast) and values less than 1 suggestive of underdispersion (overconfidence).

Similarly, the members of an ideal ensemble forecast should be indistinguishable from ground truth values. Deviations from this property on average can be diagnosed using rank histograms33. The rank histogram should be flat if the truth tends to be indistinguishable from the ensemble members, inverted U-shaped if the truth mostly ranks near the centre of the ensemble (indicating the ensembles are overdispersed), and U-shaped if the truth ranks mostly near the tails of the ensemble (indicating the ensembles are underdispersed). See Supplementary Information section A.5.4 for definitions and details.

Generally, GenCast exhibits good calibration according to these verification methods, similar to that exhibited by ENS. The spread/skill scores of GenCast are typically fractionally less than but very close to 1 (Fig. 3b–f and Supplementary Fig. B1) and also tend to have flat rank histograms (Extended Data Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. B2). By contrast, GenCast-Perturbed is consistently overconfident, showing spread/skill scores substantially less than 1 and U-shaped rank histograms.

Local surface extremes

Extreme heat, cold, wind and other severe surface weather pose serious threats to lives, health and property but can be anticipated and prepared for with the help of quality probabilistic forecasts. We assess the predictions of GenCast of whether 2 m temperature, 10 m wind speed or mean sea level pressure will exceed some extreme percentile of the climatological distribution. When comparing Brier skill scores (Supplementary Information section A.5.5)—a standard metric for evaluating probabilistic forecasts of binary events—GenCast significantly (P < 0.05) outperforms ENS on predicting the exceedance of the 99.99th, 99.9th and 99th percentiles for high 2 m temperature and 10 m wind speed, and for extremely low temperature and mean sea level pressure below the 0.01st, 0.1st and 1st percentiles (Extended Data Fig. 3). This is true across all lead times, except for lead times longer than 7 days for >99.99th percentile 10 m wind speed and certain lead times for <0.01 and <0.1 percentile mean sea level pressure, for which the improvement is not significant.

In decision-making about extreme weather events, it is often worth making preparations given even a relatively small probability of the event in question34,35. However, skill in this important regime is not well captured by the Brier score, which places equal weight on all probability decision thresholds36. We thus use relative economic value (REV) curves37,38 (for full details, see Supplementary Information section A.5.6) as a standard tool to characterize the potential value of a forecast over a range of different probability decision thresholds. Each decision threshold corresponds to a cost/loss ratio for a decision problem in which we must trade off the cost of making preparations against the loss incurred if we encounter the weather event unprepared. We draw attention in particular to lower cost/loss ratios, which are common in decision-making around extreme weather. REV is normalized relative to the value of a climatological forecast (REV = 0) and a perfect forecast (REV = 1). Note that despite the name, the ‘value’ in REV need not be economic or monetary, merely quantifiable in relative terms.

Figure 3g,h shows results for predictions of whether 2 m temperature and 10 m wind speed will exceed the 99.99th percentile relative to climatology. GenCast (blue curves) yields significantly (P < 0.05) better REV than ENS (black curves) across all cost/loss ratios, at lead times of 1 day, 5 days and 7 days (solid, dashed and dash-dot lines, respectively), with the only exceptions being those (cost/loss, lead time) combinations at which neither model outperforms climatology. Extended Data Figs. 4 and 5 show that GenCast also provides better forecasts of other levels of extreme events (other exceedance percentiles), and for other variables, including extreme low temperature and low mean sea level pressure.

Skilful joint forecast distributions

Physical constraints impose spatiotemporal dependency structure on the joint distribution of weather. For example, we know a cyclone will be a spatially local phenomenon following a single trajectory, even though its exact path may be uncertain. These spatiotemporal dependencies influence the distribution of derived quantities that are important for applications, such as cyclone tracks, or the total wind power across a specific set of wind farms. For example, the variance of the total wind power output from a set of wind farms increases when positive correlation between their wind speeds increases. It is thus important that a weather model captures these dependencies in its predictive joint distribution. We perform three evaluations on derived variables that require capturing specific aspects of this joint structure.

Spatially pooled evaluation

Neighbourhood verification is an established method from the meteorological literature that evaluates spatially pooled versions of forecasts39. Pooling mitigates the double penalty problem of standard per-grid-cell evaluation, in which the models are penalized more for predicting a feature (such as a storm) at a spatial offset than not at all. Moreover, the distribution of a spatially pooled weather quantity is influenced by spatial dependencies, and thus probabilistic pooled metrics evaluate how well a model captures some of the spatial dependency structure inherent in weather states.

We compute average-pooled and max-pooled versions of the marginal CRPS scorecard. Forecasts and analysis targets are aggregated over circular spatial regions distributed to jointly cover the surface of Earth, and CRPS is computed on these pooled quantities for a range of pooling region sizes from 120 km to 3,828 km.

Across all 5,400 pooled verification targets—spanning each variable, level, lead time and spatial scale—GenCast outperforms ENS on average-pooled CRPS in 98.1% of targets and on max-pooled CRPS in 97.6% of targets, with relative performance increasing at larger scales (Extended Data Figs. 6 and 7). GenCast-Perturbed is competitive with or better than ENS on 86% of targets for average-pooled CRPS, but only 50% of targets for max-pooled CRPS (Supplementary Figs. B15 and B16), and in both cases is worse than GenCast on 94% and 97% of targets, respectively. This suggests that GenCast captures spatial dependencies better than ENS and GenCast-Perturbed across all surface and atmospheric variables.

Regional wind power forecasting

In the electricity sector, power grid operators use regional wind power forecasts for tasks such as unit commitment and reserve quantification40, in which leveraging forecast uncertainty can improve decision-making41,42. However, forecast errors make it harder to ensure the balance of supply and demand, increasing reliance on fossil fuel-based spinning reserves40, thus undermining the potential of wind power for reducing carbon emissions43.

To estimate the potential impact of GenCast in wind energy applications, we conducted a simplified regional wind power forecasting experiment, in which 10 m wind speed of forecasts and analysis targets are interpolated at all 5,344 wind farm locations from the Global Power Plant Database44. These 10 m wind speeds are then converted to wind power using a standard idealized power curve (Supplementary Fig. A1) multiplied by the nominal capacity of each wind farm. Wind power (in megawatts) is then summed across arbitrary groupings of wind farms defined by the pooling regions from the above spatially pooled evaluation with sizes of 120 km, 240 km and 480 km.

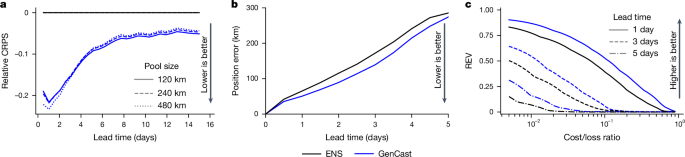

GenCast outperforms the CRPS of ENS by around 20% up to lead times of 2 days, 10–20% from 2 days to 4 days, and retains statistically significant (P < 0.05) improvements out to 7 days (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. B17). This is a substantially greater improvement than that provided by GenCast-Perturbed (Supplementary Fig. B18).

a, Relative CRPS of the total wind power summed across wind farm locations44 in pooling regions of different sizes. b, Position error of ensemble mean cyclone tracks. c, REV of tropical cyclone track probability forecasts at lead times of 1 day, 3 days and 5 days. All plots show a comparison of GenCast and ENS4.

It is important to note that this experiment does not account for complications of curtailment because of non-weather effects (for example, turbine maintenance) or grid topology. We also use 10 m wind speeds; most turbines are closer to 100 m above the ground. Nonetheless, these results indicate that GenCast provides more skilful wind forecasts that can capture joint spatial structure across real-world wind farm sites, indicating a potential value for the management and use of wind energy.

Tropical cyclones

Tropical cyclones cause thousands of deaths and tens of billions of dollars in damages on average every year. Mitigating these devastating consequences depends on accurate predictions of cyclone trajectories45. Preventative measures may be justified even when the risk of a cyclone impact is low, making probabilistic cyclone forecasts particularly important34,46. Moreover, cyclones are defined by the interactions of multiple weather variables across different atmospheric levels and over time, as such probabilistic cyclone trajectory forecasting constitutes a substantial test of both the tails and the spatiotemporal joint structure in the predictive distribution of a model. To assess the cyclone prediction skill of GenCast and ENS, we apply the TempestExtremes tropical cyclone tracker47 to GenCast, ENS, ERA5 and HRES-fc0 and evaluate the two models using established deterministic and probabilistic verification methods from the tropical cyclone literature.

First, we evaluate the position error of ensemble mean cyclone trajectories from GenCast and ENS, using a pairing procedure to ensure evaluation on the same set of cyclones. The ensemble mean track of GenCast is consistently more skilful than that of ENS. On average, GenCast gives a 12-h advantage in accuracy between 1 day and 4 days ahead (Fig. 4b), with significantly (P < 0.05) lower error between 12 h and 3.5 day lead times (inclusive, Supplementary Fig. B9).

Ensemble mean cyclone trajectories provide intuitive summaries of ensemble forecasts, but do not capture their uncertainty (or even possible multi-modality), and cannot be used to assess the ability of a model to predict cyclogenesis. We, therefore, also evaluate forecast track probability fields from GenCast and ENS—computed as the fraction of ensemble members that predict a cyclone centre passing through a given 1° grid box at a given time48. Cyclones are typically associated with low cost/loss ratios given their potentially severe consequences. The track probability forecasts of GenCast outperform those of ENS, achieving better REV at all cost/loss ratios, with the only exceptions being large cost/loss ratios for which neither model outperforms climatology (Fig. 4c). These improvements are significant (P < 0.05) in almost all cases out to 7 day lead times (Supplementary Fig. B11). This shows that GenCast can provide substantial value in decisions about when and how to prepare for tropical cyclones34. See Methods for the evaluation and cyclone tracker details and Supplementary Information section C.1 for additional cyclone visualizations.

Conclusion

Our results indicate that probabilistic weather forecasts based on MLWP can be more skilful and faster to generate than the top NWP-based ensemble forecast, ENS of ECMWF. GenCast succeeds across three key desiderata for probabilistic weather models. First, GenCast generates ensembles of sharp individual weather trajectories with realistic power spectra, rather than sets of summary statistics such as conditional means. Second, the marginal forecast distributions of GenCast (that is, forecasts for a given place and time) are well-calibrated and provide more skilful predictions than those of ENS, including better predictions of extreme events. Third, GenCast outperforms ENS across several evaluations that require capturing spatial and temporal dependencies in the joint distribution: pooled evaluation, regional wind power forecasting and tropical cyclone track prediction.

Going forward, GenCast could be further improved for operational settings in several ways. GenCast operates at 0.25° resolution, the current maximum resolution of global reanalysis data. However, it may be useful to scale up to higher resolution to support additional applications and match the upgraded resolution of ENS (as of mid-2023) of 0.1°. As a diffusion model, GenCast is computationally more expensive than an equivalent deterministic MLWP architecture, because it requires multiple function evaluations to sample each forecast time step. To efficiently scale to higher resolution or to move towards computational parity with GenCast-Perturbed and similar models, distillation49 and other efficiency techniques should be explored. Furthermore, previous work has shown that the performance of MLWP models that are trained on reanalysis can be further improved by fine-tuning using operational data, such as HRES analysis inputs and targets30. This underscores the importance for GenCast of traditional NWP-based data assimilation for providing training and initialization data.

Together, our results open a new front in weather forecasting, promising greater accuracy, efficiency and accessibility across a wide range of settings. More generally, our work demonstrates that cutting-edge generative AI methods can capture very high-dimensional and complex distributions over rich temporal dynamics, with sufficient accuracy and reliability to support effective decision-making in crucial applications.

Methods

Task definition and general approach

Probabilistic weather forecasting with machine learning

Nature (2024)

Abstract

Weather forecasts are fundamentally uncertain, so predicting the range of probable weather scenarios is crucial for important decisions, from warning the public about hazardous weather to planning renewable energy use. Traditionally, weather forecasts have been based on numerical weather prediction (NWP)1, which relies on physics-based simulations of the atmosphere. Recent advances in machine learning (ML)-based weather prediction (MLWP) have produced ML-based models with less forecast error than single NWP simulations2,3. However, these advances have focused primarily on single, deterministic forecasts that fail to represent uncertainty and estimate risk. Overall, MLWP has remained less accurate and reliable than state-of-the-art NWP ensemble forecasts. Here we introduce GenCast, a probabilistic weather model with greater skill and speed than the top operational medium-range weather forecast in the world, ENS, the ensemble forecast of the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasts4. GenCast is an ML weather prediction method, trained on decades of reanalysis data. GenCast generates an ensemble of stochastic 15-day global forecasts, at 12-h steps and 0.25° latitude–longitude resolution, for more than 80 surface and atmospheric variables, in 8 min. It has greater skill than ENS on 97.2% of 1,320 targets we evaluated and better predicts extreme weather, tropical cyclone tracks and wind power production. This work helps open the next chapter in operational weather forecasting, in which crucial weather-dependent decisions are made more accurately and efficiently.

Similar content being viewed by others

Main

Every day, people, governments and other organizations around the world rely on accurate weather forecasts to make many key decisions—whether to carry an umbrella, when to flee an approaching tropical cyclone, how to plan the use of renewable energy in a power grid, or how to prepare for a heatwave. But forecasts will always have some uncertainty, because we can only partially observe the current weather, and even our best weather models are imperfect. The highly non-linear physics of weather means that small initial uncertainties and errors can rapidly grow into large uncertainties about the future5. Making important decisions often requires knowing not just a single probable scenario but the range of possible scenarios and how likely they are to occur.

Traditional weather forecasting is based on numerical weather prediction (NWP) algorithms, which approximately solve the equations that model atmospheric dynamics. Deterministic NWP methods map the current estimate of the weather to a forecast of how the future weather will unfold over time. To model the probability distribution of different future weather scenarios6,7, weather agencies increasingly rely on ensemble forecasts, which generate several NWP-based forecasts, each of which models a single possible scenario4,8,9,10,11. ENS of the European Centre for Medium-Range Weather Forecasting (ECMWF)4 is the state-of-the-art NWP-based ensemble forecast in the broader Integrated Forecast System of the ECMWF and will subsume their deterministic forecast, HRES, going forward12.

ENS satisfies several key desiderata of a probabilistic weather model. First, its ensemble members represent sharp and spectrally realistic individual weather trajectories, as opposed to some summary statistic such as a conditional mean. Second, it produces skilful and calibrated marginal forecast distributions (forecasts of the weather at a given place and time), which is important for many day-to-day users of weather forecasts. Third, it captures the aspects of the joint spatiotemporal structure of the forecast distribution that are crucial for probabilistic modelling of large-scale phenomena such as cyclones and for applications such as forecasting distributed energy generation. Nonetheless, ENS—along with other NWP-based ensemble forecasts—is still prone to errors, is slow to run and is time-consuming to engineer.

Recent advances in machine learning (ML)-based weather prediction (MLWP) have been shown to provide greater accuracy and efficiency than NWP for non-probabilistic forecasts2,3,13,14,15,16,17,18. Rather than forecasting a single weather trajectory, or a distribution of trajectories, these methods have largely focused on forecasting the mean of the probable trajectories, with relatively little emphasis on quantifying the uncertainty associated with a forecast. They are typically trained to minimize the mean squared error (MSE) of their predictions and as a result tend to produce blurry forecasts, especially at longer lead times, rather than a specific realization of a possible weather state2. There have been limited attempts to use traditional initial condition perturbation methods to produce ensembles with MLWP-based forecasts3,15,18,19. However, these methods have not addressed the issue of blurring—meaning that their ensemble members do not represent realistic samples from the weather distribution—and they have not rivalled operational ensemble forecasts such as ENS. An exception is NeuralGCM20, a hybrid NWP–MLWP method, which combines the dynamical core of a traditional NWP with local ML-based parameterizations and shows competitive performance with operational ensemble forecasts. However, ensembles of this hybrid model have 1.4° spatial resolution, which is an order of magnitude coarser than operational NWP-based forecasts.

This work presents GenCast, the first MLWP method, to our knowledge, that significantly outperforms the top operational ensemble NWP model, ENS. We demonstrate that GenCast generates ensembles of realistic individual weather trajectories, providing both better marginal and better joint forecast distributions than ENS.

GenCast

GenCast is a probabilistic weather model that generates global 15-day ensemble forecasts at 0.25° resolution, which are more accurate than the top operational ensemble system, ENS of ECMWF. Generating a single 15-day GenCast forecast takes about 8 min on a Cloud TPUv5 device, and an ensemble of forecasts can be generated in parallel.

GenCast models the conditional probability distribution P(Xt+1|Xt, Xt−1) of the future weather state Xt+1 conditional on the current and previous weather states. A forecast trajectory X1:T of length T is modelled by conditioning on the initial and previous states, (X0, X−1), and factoring the joint distribution over successive states,

each of which is sampled autoregressively.

The representation of the global weather state, X, consists of six surface variables and six atmospheric variables at 13 vertical pressure levels (Extended Data Table 1) on an equiangular 0.25° latitude–longitude grid. The forecast horizon is 15 days, with 12 h between successive steps t and t + 1, so T = 30. We train GenCast using analysis for X, which represents the best estimate of the weather state, inferred from observations.

GenCast is implemented as a conditional diffusion model21,22,23, a generative ML method that can model the probability distribution of complex data and generate new samples. Diffusion models underpin many of the recent advances in modelling natural images, sounds and videos under the umbrella of generative AI24,25. Diffusion models work through a process of iterative refinement. A future atmospheric state, Xt+1, is produced by iteratively refining a candidate state initialized as pure noise, , conditioned on the previous two atmospheric states (Xt, Xt−1). The blue box in Fig. 1 shows how the first forecast step is generated from the initial conditions and how the full trajectory, X1:T, is generated autoregressively. Because each time step in a forecast is initialized with noise (), the process can be repeated with different noise samples to generate an ensemble of trajectories. See Methods for further details of the sampling process.

The blue box shows how, conditioning on inputs (X0, X−1), an initial noise sample, , is refined by the neural network refinement function, rθ (green box), which is parameterized by θ. The resulting is the first refined candidate state, and this process repeats N times. The final is then added as a residual to X0 to produce the weather state at the next time step, X1. This process then repeats autoregressively, T = 30 times, conditioning on (Xt, Xt−1) and using a new initial noise sample at each step to produce the full weather trajectory sample (for visual clarity, we illustrate the previous state in parentheses, (Xt−1), below the current state, Xt, but note that it is not added to as a residual for predicting Xt+1). Each trajectory generated by independent noise samples represents a sample from, P(X1:T|X0, X−1).

At each stage of the iterative refinement process, GenCast makes use of a denoiser neural network, which is trained to remove noise artificially added to atmospheric states using the loss function described in the Methods. The architecture of the denoiser comprises an encoder, processor and decoder. The encoder component maps a noisy target state , as well as the conditioning (Xt, Xt−1), from the equiangular 0.25° latitude–longitude grid to an internal learned representation defined on a six-times-refined icosahedral mesh. The processor component is a graph transformer26 in which each node attends to its k-hop neighbourhood on the mesh. The decoder component maps from the internal mesh representation back to a denoised target state, defined on the grid.

GenCast is trained on 40 years of best-estimate analysis from 1979 to 2018, taken from the publicly available ERA5 (fifth generation ECMWF reanalysis) reanalysis dataset27. Reanalysis provides a reconstruction of past weather by computing analysis for historical dates and times. For simplicity, we refer to ERA5 reanalysis as analysis from here on. Full details of the GenCast architecture and training protocol are provided in the Methods. When evaluating GenCast, we initialize it with ERA5 analysis.

As an illustrative example, Fig. 2b–d,h–j showcases GenCast forecast samples and Fig. 2n–q provides an example of how they can be used in important downstream applications, such as predicting the paths of tropical cyclones. Typhoon Hagibis—the costliest tropical cyclone of 2019—is shown as a representative case study. When initialized 7 days before the landfall of Typhoon Hagibis, the predicted trajectories of GenCast exhibit high uncertainty, covering a wide range of possible scenarios. At shorter lead times, the uncertainty of GenCast about the path of the cyclone is lower, reflecting greater confidence about the landfall timing and location.

a, The ERA5 analysis state27 for specific humidity at 700 hPa, at validity time 06 UTC, 12 October 2019, shows Typhoon Hagibis near the centre of the frame, hours before making landfall in Japan. b–d, Sample 1 (b), sample 2 (c) and sample 3 (d) GenCast forecast states, initialized one day earlier, show how the samples are sharp and very similar to one another. e, The GenCast ensemble mean, obtained by computing the mean of 50 sample states such as in b–d, is somewhat blurry, showing how uncertainty results in a blurrier average state. f, Sample 1 forecast state from GenCast-Perturbed, initialized one day earlier as in b–e, is blurry, similar to a single-step ensemble mean. g, The spatial power spectrum of the states in a, b, e and f, in which the line colours match the frames of the panels, show how spectra of the GenCast samples closely match with that of ERA5, whereas the blurrier GenCast ensemble mean and GenCast-Perturbed states have less power at shorter wavelengths. h–m, These subplots are analogous to b–g, except the forecasts are initialized 15 days earlier. The GenCast samples are still sharp (h–j) and GenCast-Perturbed (l) is still equally blurry, whereas the GenCast ensemble mean (k) is even blurrier than at 1-day lead time. This is also reflected in the power spectrum (m). n–q, The trajectory of Typhoon Hagibis based on ERA527 (in red) and the ensemble of tropical cyclone trajectories from GenCast (in blue) up to a validity time 4 h before the cyclone made landfall in Japan. GenCast forecasts are shown at lead times of 7 days, 3 days, 5 days and 1 day. The blue and red circles show cyclone locations at the validity time. At long lead times, the cyclone trajectories have a substantial spread, whereas for the shorter lead times, the predictive uncertainty collapses to a small range of trajectories. Typhoon Hagibis represents the 55th percentile of GenCast’s ensemble mean position error among tropical cyclones in 2019.

Baselines

We compare GenCast to ENS, currently the best operational ensemble forecast, which we regridded from its (pre-June 2023) native 0.2° latitude–longitude resolution to 0.25°. ENS contains 50 perturbed ensemble members, so we used 50-member GenCast ensembles to perform all evaluations. The public TIGGE archive28 only makes all 50 ENS ensemble members available for surface variables and for atmospheric variables at eight pressure levels in the troposphere. So these are the variables and levels we compare models on.

We also develop a deterministic 12 h step forecast model using the GenCast architecture, to serve as a strong ML baseline and an ablation of the role of diffusion. We used this model to generate ensemble forecasts (denoted as GenCast-Perturbed) by initializing it using ERA5 analysis perturbed by Gaussian Process noise; full details are in Supplementary Information section A.4.

For a fair comparison of models, we evaluate each model against its corresponding best-estimate analysis, following established practice2,29. We thus evaluate the operational forecasts of ECMWF against HRES-fc030 (a dataset comprising the initial conditions used for the HRES deterministic forecast of ECMWF), and we evaluate ML models that were trained and initialized using ERA5, against ERA530.

We use 2019 as our test period, and, following the protocol in ref. 2, we initialize ML models using ERA5 at 06 UTC and 18 UTC, as these benefit from only 3 h of look-ahead (with the exception of sea surface temperature, which in ERA5 is updated once per 24 h). This ensures ML models are not afforded an unfair advantage by initializing from states with longer look-ahead windows.

We follow a standard verification practice29 in evaluating ensemble forecasts using best-estimate analysis as ground truth. However, we note that this does not reward representing initial condition uncertainty. We also note that we evaluate the raw output of GenCast against that of ENS, following standard practice in the field. Both MLWP and NWP forecasts can be further improved by post-processing methods, and the relative impact of these methods on the two approaches is an interesting direction for future work.

Realism of GenCast samples

Figure 2 shows some of the forecast samples of GenCast for Typhoon Hagibis, shortly before it made landfall in Japan on 12 October 2019. Figure 2b–e,g,h–k,m shows that GenCast forecasts are sharp and have spherical harmonic power spectra that closely match the ERA5 ground truth at both 1- and 15-day lead times. This reflects how the ensemble members of GenCast, like those of ENS, represent realistic samples of the weather. As expected, the GenCast ensemble mean is blurry, losing power at high frequencies (see also Supplementary Figs. B5 and B6). Forecasts by deterministic models trained to minimize forecast MSE—including top deterministic MLWP models such as GraphCast2—are blurred and closer to the ensemble mean2. Ensemble members generated by perturbing these deterministic models also blur. This is especially true for multi-step-trained models such as GraphCast, but it is also true (albeit to a lesser extent) for models such as GenCast-Perturbed (Fig. 2f,l), which are only trained to predict a one-step forecast-distribution mean.

Skilful marginal forecast distributions

Many day-to-day users of weather forecasts rely on the spatiotemporal marginals of the forecast distributions, that is, the weather forecast for a given place and time. We evaluate the per-grid-cell marginals of GenCast and ENS in terms of overall forecast skill, calibration and performance on extreme weather prediction.

Ensemble skill

The CRPS31 is a standard measure of the skill of a probabilistic forecast. It measures how well the marginal distributions of the forecast represent the ground truth, and it is minimized, in expectation, by a forecast whose marginals reflect true predictive uncertainty. See Supplementary Information section A.5.1 for the mathematical definition of CRPS. As shown in the scorecard of Fig. 3, the forecasts of GenCast are significantly more skilful (P < 0.05) than that of ENS on 97.2% of our 1,320 variable, lead time and vertical level combinations (and 99.6% of targets at lead times greater than 36 h). Although dependencies across weather variables mean that these 1,320 scorecard targets do not each represent independent forecast tasks, such scorecards are a standard means of summarizing model performance. The largest improvements of GenCast are often at shorter lead times up to around 3–5 days, for surface variables, as well as temperature and specific humidity at higher pressure levels, for which the CRPS skill scores range between 10% and 30% better. GenCast-Perturbed also achieves strong results, with better or competitive CRPS compared with ENS on 82% of scorecard targets (Supplementary Fig. B7) but is still definitively worse than that of GenCast, which outperforms the CRPS of GenCast-Perturbed in 99% of targets (Extended Data Fig. 8 and Supplementary Fig. B8). Owing to our lack of confidence in the quality of ERA5 precipitation data, we exclude precipitation results from our main results and refer readers to Supplementary Information section B.2.

a, CRPS scores for GenCast versus ENS4 in 2019. The scorecard compares CRPS skill between GenCast and ENS across all variables and eight pressure levels. Dark-blue cells on the scorecard indicate a variable, lead time and level combination for which GenCast has 20% better (that is, lower) CRPS than ENS, whereas dark-red cells indicate 20% lower CRPS for ENS (white means they perform equally). The results show that GenCast significantly (P < 0.05) outperforms ENS on 97.2% of all reported variable, lead time and level combinations. Hatched regions indicate neither model is significantly better. b–f, Spread/skill scores for GenCast and ENS for selected variables. Both models are generally well-calibrated with spread/skill close to 1. g,h, REV for predictions of the exceedance of the 99.99th percentile for 2 m temperature and 10 m wind speed, at lead times of 1 day, 5 days and 7 days. GenCast consistently achieves greater REV than ENS whenever either forecast is better than climatology, particularly at small cost/loss ratios.

We also compared the root mean squared error (RMSE) of the ensemble means of GenCast and ENS. The ensemble-mean RMSE measures how closely the mean of an ensemble of forecasts matches ground truth. Although RMSE is a common metric for deterministic forecasts, it does not account for uncertainty, which is central to probabilistic verification. Nonetheless, as shown in Extended Data Fig. 1, the ensemble mean RMSE of GenCast is as good or better than that of ENS on 96% of targets and significantly better (P < 0.05) on 78% of targets.

Ensemble calibration

For a probabilistic forecast to be useful, it should be well-calibrated: it should know when it may be wrong and have confidence when it is likely to be right. This is a crucial aspect of the quality of the forecast distribution, allowing a decision-maker to hedge their choices in proportion to the confidence of the forecast. Two common tools in the weather community for evaluating calibration of the marginal forecast distributions, on average, are spread/skill ratios and rank histograms.

Well-calibrated probabilistic forecasts exhibit uncertainty (as measured by ensemble spread), which is commensurate on average with the size of their errors32. The degree to which this relationship holds can be quantified by the spread/skill ratio defined in Supplementary Information section A.5.3. This ratio should be 1 for a perfect ensemble forecast, with values greater than 1 suggestive of overdispersion (an underconfident forecast) and values less than 1 suggestive of underdispersion (overconfidence).

Similarly, the members of an ideal ensemble forecast should be indistinguishable from ground truth values. Deviations from this property on average can be diagnosed using rank histograms33. The rank histogram should be flat if the truth tends to be indistinguishable from the ensemble members, inverted U-shaped if the truth mostly ranks near the centre of the ensemble (indicating the ensembles are overdispersed), and U-shaped if the truth ranks mostly near the tails of the ensemble (indicating the ensembles are underdispersed). See Supplementary Information section A.5.4 for definitions and details.

Generally, GenCast exhibits good calibration according to these verification methods, similar to that exhibited by ENS. The spread/skill scores of GenCast are typically fractionally less than but very close to 1 (Fig. 3b–f and Supplementary Fig. B1) and also tend to have flat rank histograms (Extended Data Fig. 2 and Supplementary Fig. B2). By contrast, GenCast-Perturbed is consistently overconfident, showing spread/skill scores substantially less than 1 and U-shaped rank histograms.

Local surface extremes

Extreme heat, cold, wind and other severe surface weather pose serious threats to lives, health and property but can be anticipated and prepared for with the help of quality probabilistic forecasts. We assess the predictions of GenCast of whether 2 m temperature, 10 m wind speed or mean sea level pressure will exceed some extreme percentile of the climatological distribution. When comparing Brier skill scores (Supplementary Information section A.5.5)—a standard metric for evaluating probabilistic forecasts of binary events—GenCast significantly (P < 0.05) outperforms ENS on predicting the exceedance of the 99.99th, 99.9th and 99th percentiles for high 2 m temperature and 10 m wind speed, and for extremely low temperature and mean sea level pressure below the 0.01st, 0.1st and 1st percentiles (Extended Data Fig. 3). This is true across all lead times, except for lead times longer than 7 days for >99.99th percentile 10 m wind speed and certain lead times for <0.01 and <0.1 percentile mean sea level pressure, for which the improvement is not significant.

In decision-making about extreme weather events, it is often worth making preparations given even a relatively small probability of the event in question34,35. However, skill in this important regime is not well captured by the Brier score, which places equal weight on all probability decision thresholds36. We thus use relative economic value (REV) curves37,38 (for full details, see Supplementary Information section A.5.6) as a standard tool to characterize the potential value of a forecast over a range of different probability decision thresholds. Each decision threshold corresponds to a cost/loss ratio for a decision problem in which we must trade off the cost of making preparations against the loss incurred if we encounter the weather event unprepared. We draw attention in particular to lower cost/loss ratios, which are common in decision-making around extreme weather. REV is normalized relative to the value of a climatological forecast (REV = 0) and a perfect forecast (REV = 1). Note that despite the name, the ‘value’ in REV need not be economic or monetary, merely quantifiable in relative terms.

Figure 3g,h shows results for predictions of whether 2 m temperature and 10 m wind speed will exceed the 99.99th percentile relative to climatology. GenCast (blue curves) yields significantly (P < 0.05) better REV than ENS (black curves) across all cost/loss ratios, at lead times of 1 day, 5 days and 7 days (solid, dashed and dash-dot lines, respectively), with the only exceptions being those (cost/loss, lead time) combinations at which neither model outperforms climatology. Extended Data Figs. 4 and 5 show that GenCast also provides better forecasts of other levels of extreme events (other exceedance percentiles), and for other variables, including extreme low temperature and low mean sea level pressure.

Skilful joint forecast distributions

Physical constraints impose spatiotemporal dependency structure on the joint distribution of weather. For example, we know a cyclone will be a spatially local phenomenon following a single trajectory, even though its exact path may be uncertain. These spatiotemporal dependencies influence the distribution of derived quantities that are important for applications, such as cyclone tracks, or the total wind power across a specific set of wind farms. For example, the variance of the total wind power output from a set of wind farms increases when positive correlation between their wind speeds increases. It is thus important that a weather model captures these dependencies in its predictive joint distribution. We perform three evaluations on derived variables that require capturing specific aspects of this joint structure.

Spatially pooled evaluation

Neighbourhood verification is an established method from the meteorological literature that evaluates spatially pooled versions of forecasts39. Pooling mitigates the double penalty problem of standard per-grid-cell evaluation, in which the models are penalized more for predicting a feature (such as a storm) at a spatial offset than not at all. Moreover, the distribution of a spatially pooled weather quantity is influenced by spatial dependencies, and thus probabilistic pooled metrics evaluate how well a model captures some of the spatial dependency structure inherent in weather states.

We compute average-pooled and max-pooled versions of the marginal CRPS scorecard. Forecasts and analysis targets are aggregated over circular spatial regions distributed to jointly cover the surface of Earth, and CRPS is computed on these pooled quantities for a range of pooling region sizes from 120 km to 3,828 km.

Across all 5,400 pooled verification targets—spanning each variable, level, lead time and spatial scale—GenCast outperforms ENS on average-pooled CRPS in 98.1% of targets and on max-pooled CRPS in 97.6% of targets, with relative performance increasing at larger scales (Extended Data Figs. 6 and 7). GenCast-Perturbed is competitive with or better than ENS on 86% of targets for average-pooled CRPS, but only 50% of targets for max-pooled CRPS (Supplementary Figs. B15 and B16), and in both cases is worse than GenCast on 94% and 97% of targets, respectively. This suggests that GenCast captures spatial dependencies better than ENS and GenCast-Perturbed across all surface and atmospheric variables.

Regional wind power forecasting

In the electricity sector, power grid operators use regional wind power forecasts for tasks such as unit commitment and reserve quantification40, in which leveraging forecast uncertainty can improve decision-making41,42. However, forecast errors make it harder to ensure the balance of supply and demand, increasing reliance on fossil fuel-based spinning reserves40, thus undermining the potential of wind power for reducing carbon emissions43.

To estimate the potential impact of GenCast in wind energy applications, we conducted a simplified regional wind power forecasting experiment, in which 10 m wind speed of forecasts and analysis targets are interpolated at all 5,344 wind farm locations from the Global Power Plant Database44. These 10 m wind speeds are then converted to wind power using a standard idealized power curve (Supplementary Fig. A1) multiplied by the nominal capacity of each wind farm. Wind power (in megawatts) is then summed across arbitrary groupings of wind farms defined by the pooling regions from the above spatially pooled evaluation with sizes of 120 km, 240 km and 480 km.

GenCast outperforms the CRPS of ENS by around 20% up to lead times of 2 days, 10–20% from 2 days to 4 days, and retains statistically significant (P < 0.05) improvements out to 7 days (Fig. 4a and Supplementary Fig. B17). This is a substantially greater improvement than that provided by GenCast-Perturbed (Supplementary Fig. B18).

a, Relative CRPS of the total wind power summed across wind farm locations44 in pooling regions of different sizes. b, Position error of ensemble mean cyclone tracks. c, REV of tropical cyclone track probability forecasts at lead times of 1 day, 3 days and 5 days. All plots show a comparison of GenCast and ENS4.

It is important to note that this experiment does not account for complications of curtailment because of non-weather effects (for example, turbine maintenance) or grid topology. We also use 10 m wind speeds; most turbines are closer to 100 m above the ground. Nonetheless, these results indicate that GenCast provides more skilful wind forecasts that can capture joint spatial structure across real-world wind farm sites, indicating a potential value for the management and use of wind energy.

Tropical cyclones

Tropical cyclones cause thousands of deaths and tens of billions of dollars in damages on average every year. Mitigating these devastating consequences depends on accurate predictions of cyclone trajectories45. Preventative measures may be justified even when the risk of a cyclone impact is low, making probabilistic cyclone forecasts particularly important34,46. Moreover, cyclones are defined by the interactions of multiple weather variables across different atmospheric levels and over time, as such probabilistic cyclone trajectory forecasting constitutes a substantial test of both the tails and the spatiotemporal joint structure in the predictive distribution of a model. To assess the cyclone prediction skill of GenCast and ENS, we apply the TempestExtremes tropical cyclone tracker47 to GenCast, ENS, ERA5 and HRES-fc0 and evaluate the two models using established deterministic and probabilistic verification methods from the tropical cyclone literature.

First, we evaluate the position error of ensemble mean cyclone trajectories from GenCast and ENS, using a pairing procedure to ensure evaluation on the same set of cyclones. The ensemble mean track of GenCast is consistently more skilful than that of ENS. On average, GenCast gives a 12-h advantage in accuracy between 1 day and 4 days ahead (Fig. 4b), with significantly (P < 0.05) lower error between 12 h and 3.5 day lead times (inclusive, Supplementary Fig. B9).

Ensemble mean cyclone trajectories provide intuitive summaries of ensemble forecasts, but do not capture their uncertainty (or even possible multi-modality), and cannot be used to assess the ability of a model to predict cyclogenesis. We, therefore, also evaluate forecast track probability fields from GenCast and ENS—computed as the fraction of ensemble members that predict a cyclone centre passing through a given 1° grid box at a given time48. Cyclones are typically associated with low cost/loss ratios given their potentially severe consequences. The track probability forecasts of GenCast outperform those of ENS, achieving better REV at all cost/loss ratios, with the only exceptions being large cost/loss ratios for which neither model outperforms climatology (Fig. 4c). These improvements are significant (P < 0.05) in almost all cases out to 7 day lead times (Supplementary Fig. B11). This shows that GenCast can provide substantial value in decisions about when and how to prepare for tropical cyclones34. See Methods for the evaluation and cyclone tracker details and Supplementary Information section C.1 for additional cyclone visualizations.

Conclusion

Our results indicate that probabilistic weather forecasts based on MLWP can be more skilful and faster to generate than the top NWP-based ensemble forecast, ENS of ECMWF. GenCast succeeds across three key desiderata for probabilistic weather models. First, GenCast generates ensembles of sharp individual weather trajectories with realistic power spectra, rather than sets of summary statistics such as conditional means. Second, the marginal forecast distributions of GenCast (that is, forecasts for a given place and time) are well-calibrated and provide more skilful predictions than those of ENS, including better predictions of extreme events. Third, GenCast outperforms ENS across several evaluations that require capturing spatial and temporal dependencies in the joint distribution: pooled evaluation, regional wind power forecasting and tropical cyclone track prediction.

Going forward, GenCast could be further improved for operational settings in several ways. GenCast operates at 0.25° resolution, the current maximum resolution of global reanalysis data. However, it may be useful to scale up to higher resolution to support additional applications and match the upgraded resolution of ENS (as of mid-2023) of 0.1°. As a diffusion model, GenCast is computationally more expensive than an equivalent deterministic MLWP architecture, because it requires multiple function evaluations to sample each forecast time step. To efficiently scale to higher resolution or to move towards computational parity with GenCast-Perturbed and similar models, distillation49 and other efficiency techniques should be explored. Furthermore, previous work has shown that the performance of MLWP models that are trained on reanalysis can be further improved by fine-tuning using operational data, such as HRES analysis inputs and targets30. This underscores the importance for GenCast of traditional NWP-based data assimilation for providing training and initialization data.

Together, our results open a new front in weather forecasting, promising greater accuracy, efficiency and accessibility across a wide range of settings. More generally, our work demonstrates that cutting-edge generative AI methods can capture very high-dimensional and complex distributions over rich temporal dynamics, with sufficient accuracy and reliability to support effective decision-making in crucial applications.

Methods

Task definition and general approach

Google Says AI Weather Model Masters 15-day Forecast

===

.png)

No comments:

Post a Comment