The Joseph Smith Birthplace Memorial is a granite obelisk on a hill in the White River Valley near Sharon and South Royalton in the U.S. state of Vermont. It marks the spot where Joseph Smith was born on December 23, 1805.[1]

The monument was erected by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), which recognizes Smith as its first president and founding prophet. The LDS Church continues to own and operate the site as a tourist attraction.

The monument was erected by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), which recognizes Smith as its first president and founding prophet. The LDS Church continues to own and operate the site as a tourist attraction.

Need to get into the holiday spirit? Travel to a hilltop in South Royalton, where 200,000 holiday lights twinkle in the snow.

The Joseph Smith Birthplace Memorial showcases one of the most festive holiday displays in Vermont, with trees, bushes, and buildings illuminated in red, green, and gold.

An Annual Tradition of Holiday Lights

The impressive showcase of holiday lights are up now through New Year’s Day, and visitors are welcome to stop by to see the display between 4:30 and 11 p.m.

The annual tradition, which started in 1988, draws about 15,000 visitors each year and continues to grow in popularity.

This 400-plus acre property is also interesting to visit beyond the holiday season. The complex, maintained by the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, begins with a steep hill of maples leading to a hilltop visitors’ center and a 38.5-foot-high shaft and sits above a 12-foot base.

The shaft, cut from Barre granite in 1905, marks the site where the founder of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints was born and lived as a child. Each foot on the shaft marks a year in the life of the prophet, who was later killed by a mob in Carthage, Illinois, in 1844. The memorial celebrates his story and life in an environment that is warm and inviting.

During the holidays, the Joseph Smith Birthplace Memorial also features a large nativity scene and a stable with a donkey and two sheep. After this week’s winter storm, the site looks as festive as ever.

Regardless of your religion or beliefs, you’ll enjoy a sense of peaceful holiday beauty along this rural Vermont hilltop.

If You Go: The Joseph Smith Birthplace Memorial is located at 357 LDS Lane in South Royalton.

Stop by the visitors’ center from 9 a.m. to 9 p.m., and see the

lights between 4:30 and 11 p.m. now through Jan. 1. Admission is free.

Church History

Historical Cliffhanger: How We Came to Mark Joseph Smith’s Birthplace

Sign up for Meridian’s Free Newsletter, please CLICK HERE

On Dec. 23, we remember the birth of Joseph Smith, coming right at a time when in our northern hemisphere the light begins to return to the earth.

In August of 1894, while on one of his many trips, Junius Wells, a Latter-day Saint leader, took a detour through Vermont looking for something that mattered to him—the birthplace of Joseph Smith.

Junius Wells.

At the Sharon Town Clerk’s office, he met Harvey Black, a long-time resident of the area, who led him across a field to an old cellar hole. The site consisted of crumbling walls, a few foundation stones and overgrown shrubbery. This was the physical and largely-forgotten remains of the Smith home where the Prophet Joseph Smith was born.

As he rode away from the birthplace, Wells said to himself, “sometime we ought to mark this place with a monument of the faith of our people in Joseph Smith the Prophet.”

Then in March, 1905, Wells found himself again in New England. This time he was contracting for a piece of Vermont granite for his father’s headstone in Salt Lake City. The monument contractor was Riley C. Bowers from Montpelier. In the course of this exchange, Wells mentioned the idea of a monument to Joseph Smith in Sharon, to commemorate the centennial anniversary of his birth in 1805. Bowers thought the idea was certainly workable, so with this endorsement, Wells returned to Salt Lake to share his idea with the First Presidency of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.

Consider this timing. The centennial was only a few months away, and Wells would be erecting a 38-1/2 foot obelisk of granite weighing thousands of pounds. He would not only be looking for the perfect stone, but having to transport it, at least part of the way, on a wagon across a muddy track. This was all but impossible. Wells would need a miracle—in fact many miracles—to make this happen.

In a letter dated April 1, 1905, Wells made his pitch to President Joseph F. Smith and his counselors. Although the letter has not survived, Wells offered to supervise the project and took the liberty of proposing a monument for the site recommending dimensions, inscription and even included a sketch of the proposal.

The First Presidency was a little more guarded, and instructed Wells that he first needed to verify the location of the Prophet’s birth and then attempt to purchase the land. Only then would they consider the proposal for building a monument. The clock was ticking.

On May 10, 1905, Wells left for Vermont, determined to erect a monument in six months that would typically take ten to twelve months to accomplish.

He was going to need some help.

The Easy Part

Wells settled into the South Royalton House. This would now become his headquarters. The local newspapers soon picked up on his presence in town. They reported that “he made no secret of his purpose which was to settle indubitably the exact spot where Joseph Smith was born and to acquire the premises and to erect a monument thereon.”

Wells recalled that with the help of Daniel E. Parkhurst, a shoemaker, town clerk and Treasurer for Sharon, records were found tracing the Solomon Mack property back to King George III and New Hampshire Governor Benning Wentworth in 1761. Next, visiting William Skinner, town clerk of Royalton, he found out that the Mack property lay both in Sharon and in Royalton townships.

Wells identified that C.H. Robinson presently owned the land in both townships. On May 19, 1905, Wells visited the site with Benjamin Cole Latham who gave testimony to it being the birthplace site. Others like Maria Griffith and Harvey Smith went on record with their own testimonials. The help Wells had hoped for was pouring in….

Wells bargained with C.H. Robinson for the purchase of 68 acres as well as a narrow strip of land connecting the birthplace site with Dairy Hill Road. The transaction also included two springs, the Solomon Mack foundation site, the White Brook and the “Old Sharon Road”.

Junius Wells then returned to Salt Lake City to attend to the dedication of a headstone he was having erected for his father, built by the R.C. Bowers granite company of Montpelier, Vermont. It was a 15-foot tall obelisk. His father, Daniel Wells, had died in 1891, and Junius was just now finally having the stone put in place. This headstone’s size and shape were all indicative of the life of his father. This would be a “typecast” of what Junius would eventually do at the Joseph Smith monument site.

During the first week of June 1905, Wells prepared for the First Presidency, a report of his activities in Vermont and a detailed sketch of the monument he envisioned. He suggested it would be a 38-1/2 foot shaft of gray “Barre granite”. He also proposed the tribute that would appear on the Inscription Die and the cap stone.

After some deliberation, the First Presidency approved the project with only one minor inscription change. By July 1, 1905, the announcement of the project was made public. On July 6th Wells was given full power of attorney to “erect a granite monument in memory of the Prophet Joseph Smith and Patriarch Hyrum Smith”. Wells now had a carte blanche to carry out the project.

This was the easy part, now the fun would begin.

How Do You Find the Perfect Stone?

By July 13th, Wells was back in Vermont, a state built on a granite bedrock. He went immediately to Barre, where over one-hundred quarry firms were located. On the 24th of July, Wells awarded the general contract to his friend, the owner of the R.C. Bowers Granite Company of Montpelier.

Barre Quarry Workers

Wells moved his residence to Montpelier so he could personally supervise the work. He had five months to complete the project and every day was a day closer to the December 23rd dedication. Wells felt that his job was to “continually be pushing the project along”.

Bowers sub-contracted the quarrying to the Marr-Gordon Quarry in Barre. Wells reported; “The first success came when a piece of granite suitable for the die and capstone was found. Quarrymen soon found a piece sufficient for the first and second base (the monument has two base stones, Inscription Die, cap stone and pillar). But, after removing a large piece for the first base, they found that one corner was cut off, rendering the piece insufficient for the second base. This was very disappointing”. However, a suitable piece was soon discovered for the second base on the opposite side of the quarry.

With work slowly progressing at the quarry, Wells focused his attention to South Royalton.

Wells contracted with surveyors Walker and Gallison to start preparations for the birthplace park, roads, walks and building lots. By mid-August Wells had fifteen Italian laborers working at the site. Wells also contracted with Joseph Perkins to build a Memorial Cottage directly over the old cellar hole, and to incorporate the hearthstone in its original position, into the cottage fireplace. Wells was very conscious of the importance of the hearthstone. He said’ “if Joseph had any association with the hearthstone it was as a child, perhaps it was there that he was washed and dressed as a babe.”

But, all was not well in paradise. There were pressing issues north in Barre. Workers at the Marr-Gordon Quarry had found four pieces of stone, but the most difficult, the forty-foot shaft still remained to be located. Time was running out. Wells was searching for a “perfect shaft that would be typical of a perfect man. Joseph died at age 38 and a half years, the visible portion of the shaft needs to be 38 and a half feet tall.”

Wells was starting to get concerned and discouraged. Mr. Blakeney, the foreman tried numerous stones and various locations throughout the quarry to no avail. Wells said, “It was now a hopeless hope to me. I had not the faith in me. I had not the impression. I had been going by impressions all the way through. Somehow when I had the right impression it has come out all-right. But I have had no impressions”. With no impressions, no feelings and no revelation there would be no assurances. Wells began to wonder if his dream would ever come to pass.

Wells needed a little miracle and one was on the way.

It seems that while Junius Wells was searching for his pillar stone, the Marr-Gordon Quarry was being purchased. The buyer, Mr. James M. Boutwell, of the Boutwell, Milne & Varnum Company owned an adjoining quarry. Wells recalled that this “company took over his contract with great skill”.

Two days later in the adjoining quarry “a partly disclosed stone was found that showed great promise”. Mr. Farnsworth, the foreman said it would be a week before they could be sure if it was big enough, however, Wells said, “I believed at once we were on the right track”.

It was a happy day for Wells when Farnsworth announced that the shaft was forty-six feet long, sufficient for the monument. The rough stone weighed sixty ton and it took “the ingenuity of both Mr. Boutwell and Mr. Varnum combined to raise it out of the quarry”. A temporary railroad spur was constructed to transport the stone to the main line. It took two days to load the stone on the railroad car because the derrick could only load one end at a time.

Moving the uncut stone from the quarry.

The rough stone was sent six miles by train to the Barclay Brothers cutting and polishing shed. Upon arrival, powerful steam cranes and chains lifted the shaft off the railroad car, inverted it, and lowered it into the cutting blocks, where it was cut in just sixteen minutes. Wells marveled at “the difference when knowing how and having the mechanical means and power and not having it”. The stones were cut with remarkable skill and clarity.

It was now the first part of October, the dedication date of December 23rd was drawing near. Wells worried about the weather. The previous year two feet of snow had already fallen by the first of November.

As October drew to a close the polishing phase was completed. Wells was now faced with the prospect of transporting 100 tons of stone in a world without trucks. The 40-ton pillar seemed especially daunting. Wells recalled that no one before had moved polished stone this far and the time was tight. Fortunately for Wells a railroad line ran from Barre to Royalton. The issue was the six difficult miles from Royalton to the monument site.

Wells awarded the transportation contract to Mr. M.F. Howland of Barre. Mr. Howland recommended that a special wagon he had built for the removal of the stones at St. John’s Cathedral in New York be used to move the stones from Royalton to the monument site. The wagon had 20inch wide tires, axles eight feet long and eight inches in diameter and weighed eight tons.

With anticipation everyone waited at Royalton Village for the arrival of the stones. The base pieces would be the first to arrive. What Wells was about to learn, was his greatest challenges lay ahead. If it had taken enormous faith to hope that a 40-foot granite stone would appear in the short time frame he had, his faith would be taxed even further when it came to moving this behemoth.

The Greatest Challenge

Unloading in Royalton meant the bridge over the First Branch of the White River in South Royalton would need to be firmed up. This task required “much scavenging all over the state for the right timbers.”

The first load to leave Royalton contained the two base pieces of the monument. Mr. Ellis of Bethel quarries sent twenty horses to pull the load. Two other horses were picked up in Royalton. Once the horses had moved the load to the main road they stopped. Twenty-two horses could not move the 31 ton Base pieces up the simple rises on the White River Road.

A discouraged Mr. Wells returned to the South Royalton Inn and drafted a telegram to President Joseph F. Smith. He asked to ship the stones, to Salt Lake City to have them erected on the Temple Block. He kept the telegram in his pocket, but did not send it.

It was decided that block and tackle would be used, horses pulling in the opposite direction of each other using the largest trees as the hinged point. The winding White River Road was slow going, even with twenty-inch wheels the wagon would sink into the mud. The crew resorted to placing 10”x3” hardwood planks under the wheels. After one week the wagon had traveled two miles to the town of South Royalton.

Slowly the wagon and crew arrived at the base of Dairy Hill Road. Two miles left, unfortunately they had an 800 foot climb in front of them. The crew inched up the narrow, winding, muddy unpaved country road, using block and tackle and trees to serve as the support points.

The road behind was “strewn with trees, some large ones, that were pulled up by the roots, it looked as though a hurricane came down Dairy Hill Road”. A week later the bases arrived at the monument site.

The bases had landed in late October, but the original plan was to have had the entire monument completed by this time.

The next stone up was the 19 ton, six foot inscription die. They traveled without incident until arriving at the recently reinforced covered bridge over the Tunbridge Branch. The combined height of the wagon and die was 12’2”, but the opening in the covered bridge was 11’4”. H.C. Leonard of Barre brought down a special low-to-the-ground wagon. The low wagon would enable the die stone to pass under the covered bridge and sit lower to ground so it would not become unstable as they traveled up Dairy Hill road. This was a minor miracle that such a wagon even existed and was nearby. The large wagon then returned to Royalton to prepare to move the 40 ton shaft.

At this point Wells had four teams of local men working on the project. One team was preparing to move the shaft, one was transporting the die, one was preparing the monument and one was building the first visitors center or “Cottage” over the birthplace site. The crews were being paid well, two dollars a day with dinner furnished.

On November 7, now only a few weeks out from the centennial day when all had to be completed, Wells began to haul the shaft. It was forty feet long and weighed 80,000 pounds (40 ton). It would take thirty-three days to move the shaft to the monument location. They traveled only the length of a football field a day. Wells recalls the day they arrived at the foot of Haynes Hill. It rained all that day. In front of them lay Mr. Buttons bog or mud-hole. A neighbor was seen hurrying his empty hay wagon through the bog, “The wheels sunk deeper and deeper into the miserable little swamp”. With great difficulty four horses were required to remove the hay wagon. Wells dismissed the crew. Was it finally time to send the telegram he had been carrying? When alone, he knelt in prayer asking for a miracle. He returned to his hotel.

Late that night, a miracle happened. From out of Quebec a strong Canadian Clipper formed, a very cold nor-eastern wind blowing south.

As it picked up speed through the notched valleys of Vermont, it began to snow. The temperature dropped 35 degrees in three hours.

The crew reassembled, Mr. Buttons bog seemed to be frozen. The crew decided because of the weight of the stone and the uncertainty of the frozen ground they would lay the hard wood planks under the wheels, 9 inches thick under each wheel. As the horses heaved the weight of the load split the planks into kindling. The ground was frozen as hard as steel. The crew moved the shaft over the frozen mud hole and up the hill so quickly that it arrived a day before the inscription die. Wells asked one of the men riding with him if he believed in miracles, the man replied, “I almost believe it”.

The 10-ton molded cap was the last stone to arrive. It was the lightest of the stones but required a drawn of 14 horses. This was due to the small 6-inch wide wheels. If they stopped at all they would probably not get started again. The stone made the trek in just 6 hours.

It was now November 26, all stones were at the site. It was time to stand the stones. A large derrick had been sent for from Pennsylvania. It arrived the day before. To place the 40-foot shaft, it would have to be lifted 13 feet into the air, turned perpendicular and set into place. This process would take place December 8.

When the signal was given, the assembled crowd started cheering. They were suddenly stopped as they heard wells shouting Stop! Stop! Wells then dropped to his knees at the foot of the monument and offered a prayer of thanks.

He then jumped to his feet and yelled, “All right boys now I am with you, let her go.” After 137 days of anxious work and miracle after miracle, the Joseph Smith Birthplace Monument was completed, and one man’s quest for the perfect stone was over.

Don’t miss the Christmas lights - Review of Joseph Smith Birthplace Memorial, South Royalton, VT - Tripadvisor

Senior missionaries from the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints are assigned to the birthplace site of the Prophet Joseph Smith. The senior missionaries that briefed us on the buildings and the monument were very knowledgeable about the Prophet, his family, and the time period. My wife and I arrived late afternoon after a rain shower. The fall leaves covered the black asphalt path leading to the visitor’s center. After a 30-minute overview, we were taken outside to the monument and the original foundation of Joseph Smith’s birthplace. After walking around the beautifully landscaped monument and buildings, we were asked if we wanted to see the rest of the structures on the site. We readily agreed and were driven around the grounds in an eight-passenger golf cart where we were shown foundations of homes that once belonged to Solomon Mack and Daniel Mack, Joseph Smith’s grandfather and uncle. From the top of Patriarch Hill, the highest point at the Joseph Smith Birthplace Memorial, we could see the entire monument and the surrounding countryside. In early October, the leaves were just beginning to change colors, but the view was spectacular. Again, I was amazed by the knowledge and friendliness of the senior missionaries that are on assignment for only a short period of time. From the historical and religious perspective, this is a wonderful site to visit.

Date of experience: October 2018

Early Struggles of the Smith Family

In the winter of 1807–1808, Joseph and Lucy Mack Smith prepared to move their family for the fifth time in six years. They had spent the previous three years renting from Lucy’s parents in Sharon, Vermont. Today, a monument on this 68-acre farm honors the place where Joseph Smith Jr. was born, on December 23, 1805. But Joseph Jr. likely remembered little of the farm he left as a toddler. It was Lucy’s brother’s turn for family support in the face of unpaid debts,1 and the Smith family—Joseph Sr., his expectant wife, Lucy, and their four children—were making room for their Mack relatives.

Where would Joseph and Lucy take their young family of six, soon to be seven? Eleven miles away was Tunbridge, Vermont, where Joseph’s parents, Asael and Mary Smith, still lived. Joseph’s older brother, Jesse, also had a farm nearby, though other family members had moved away years before. The Smiths were able to stay in Tunbridge until their son Samuel was born,2 but they had to move again soon, since part of the family land had recently been sold.

Perhaps the familiar sights of Tunbridge that winter reminded Joseph and Lucy of earlier shared experiences there. Lucy first met her husband in Tunbridge in 1794, and the couple spent their first years of marriage there. Yet even those years of relative calm had been preceded by great sorrow.

From Sorrow to Solace in Tunbridge (1794–1801)

When Lucy’s brother Stephen Mack visited his parents’ home in Gilsum, New Hampshire, in 1794, he found his 19-year-old sister Lucy “pensive and melancholy”3 as she struggled with the distress of their sister Lovina’s untimely death. Lucy had served as Lovina’s full-time caregiver since Lucy was 16, watching as her sister’s tuberculosis grew steadily worse. Shortly after Lovina was gone, news came that an older, married sister had died of the same disease. Lucy later wrote that at this time “often in my reflections [I] thought that life was not worth possessing.”

To distract her from her grief, Stephen Mack invited Lucy to stay with him at his home in Tunbridge, Vermont. There, Lucy’s mood began to change after she became acquainted with a tall, strong 23-year-old named Joseph Smith. Joseph and Lucy were married on January 24, 1796.

Illness and Money Troubles (1802–1803)

The new Smith family lived at the Tunbridge farm for six years before Joseph determined to try his hand at storekeeping. Renting out their house and land, Joseph and Lucy, together with two young sons Alvin and Hyrum, settled in the nearby town of Randolph early in 1802.

While in Randolph, Lucy became dangerously ill with tuberculosis—the same illness that had taken the lives of her two sisters. Her mother came and attended her day and night as Lucy wrestled with the question of whether she was ready to die. She later wrote, “During the night I made a solemn covenant with God: that, if he would let me live, I would endeavor to serve him according to the best of my abilities. Shortly after this I heard a voice say to me: ‘ . . . Let your heart be comforted, ye believe in God, believe also in me.’”

Lucy made a full and rapid recovery. As the family rejoiced over this divine blessing, Joseph learned that his 17-year-old brother Stephen Smith was not so fortunate. He died from a sudden illness a few miles away, in Royalton, Vermont, within weeks of Lucy’s recovery.

Meanwhile, Joseph’s store venture failed. To cover his setup costs, Joseph had invested in a promising venture selling American wild ginseng in Chinese markets.4 Though the trade was successful, a dishonest agent stole the profits. As a result, Joseph and Lucy sacrificed their prospering Tunbridge farm and a $1,000 wedding present to settle the family accounts.

Further Hardships (1803–1816)

Joseph and Lucy now owned no land. By renting from a network of family and friends, farming during the growing season, and coopering and teaching school during the winter, the family stayed together and even grew in size. Sophronia was born in Tunbridge. Then Grandfather Mack offered the Smiths a place to live in Sharon, where Joseph Jr. was born. After leaving Sharon in the winter of 1807–1808, the family moved again to Tunbridge, then to Royalton, Vermont. The joy of welcoming three new children mixed with sorrow when baby Ephraim lived just 11 days.5

The year 1812 saw the family in Lebanon, New Hampshire. After eight moves in 10 years, they had improved their circumstances enough that Lucy dared “to contemplate, with joy and satisfaction, the prosperity which had attended our recent exertions.” That winter, typhoid fever “raged tremendously” through the countryside, killing 6,000 people. One by one, the nine Smith children fell ill. Nine-year-old Sophronia suffered for three months, nearly losing her life. Seven-year-old Joseph Jr. was ill with the fever for only two weeks, but developed a bone marrow infection that was overcome only by an agonizing, nearly-crippling surgery.6 He walked with crutches for the next three years.

The effects of a year of illness pushed the family back to Vermont, this time to a rock-bound farm in Norwich. Here, with Don Carlos’s birth, the family grew—but little else did. After two years of successive crop failures, the Smiths were “warned out” as newcomers legally unable to claim support from the town under Vermont’s “poor laws.”7 They borrowed money and resolved to try farming one more season. Unfortunately, 1816 proved to be one of the worst years for farming in Vermont history.8 Frosts came early in the year and continued well into the summer. With nothing to sell, many farmers found themselves buying food staples far above the normal price. Along with thousands of other Vermonters, Joseph Sr. settled his accounts and traveled in search of new opportunities on the western New York frontier.

For months, Lucy and the children waited in Norwich, hoping for good news from him. At length, Joseph Smith Sr. sent word for his family to join him in a town called Palmyra, over 300 miles away in the fertile, wheat-growing Genesee country of New York.

Journey to New York (1816–1817)

Joseph Smith Jr. was almost 11 years old when he helped his mother Lucy prepare for the journey. Remembering her son’s early life, Lucy could think of nothing occurring beyond the “trivial circumstances” common to childhood. Yet even at this early age, Joseph had already seen plenty of life’s suffering, including sickness, poverty, death, and the uncertainty of frontier farming life. He had no doubt heard the stories his parents had told of losing their farm, in part through the selfish actions of others. Traveling to New York gave Joseph new chances to witness and wonder at what people do when faced with others’ vulnerability.

Creditors waited until just before the Smiths’ planned departure to demand payments on debts that Lucy had thought were already settled. Though friends urged her to take legal action, Lucy knew she would not be on even footing in court. As a mother on her own with eight children, the delays and risks of the process were far greater obstacles to her than to her creditors—and they knew it. Seeing few alternatives, Lucy gave up two-thirds of the money she had saved for the move in order to settle accounts and leave in peace.

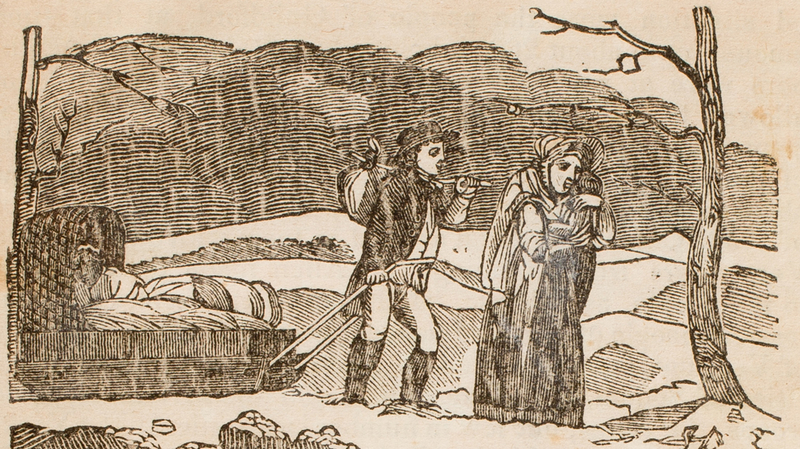

Snow already covered the ground by the time the family was underway. Young Joseph Jr. expected to ride in the family wagon, but the hired driver made him walk. When Alvin and Hyrum protested that Joseph was still weak from his surgery, the driver knocked them down with the butt of his whip.

The driver later threw the family’s belonging out of their own wagon when he learned they had run out of money 100 miles from Palmyra. Though Lucy took her wagon back, she was reduced to paying innkeepers for food and lodging with clothing or bits of cloth over the coming days. Thirteen-year-old Sophronia’s earrings made up the final payment. By then the Smiths had joined another family traveling by sleigh. As young Joseph looked to find his place, someone knocked him out of the sleigh. He later recalled he was “left to wallow in my blood until a stranger came along, picked me up, and carried me to the Town of Palmyra.”9 Helping a weak, downtrodden boy might seem an ordinary Christian kindness, but it contrasted sharply with how others had treated this family on their way.

When the Smiths’ winter journey ended after three or four weeks, they had fewer possessions and just a few cents in cash. But they had all arrived in Palmyra. Lucy reported, “The joy I felt in throwing myself and My children upon the care and affection of a tender Husband and Father doubly paid me for all I had suffered. The children surrounded their Father clinging to his neck, covering his face with tears and kisses that were heartily reciprocated by him.” Reunited, the family resolved to make another fresh start together.

Featured image courtesy of the American Antiquarian Society. All other photos courtesy of the Church History Department.

X

Lighting Christmas Lights at Joseph Smith Birthplace. Free admission, light refreshments, Christmas music, and Nativity displays at South Royalton Chapel after lighting ceremony, 7 p.m., LDS Lane, South Royalton.

.jpg)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment