Both sides get better at killing drones – and need them more than ever

After a summer of grinding attrition warfare, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine entered a dramatic new phase this fall: In a stunning battle of maneuver, a Ukrainian counteroffensive routed Russian forces in Kharkiv province, and then northern Kherson province. Kyiv’s battlefield fortunes have so improved that many analysts believe the forthcoming infusion of poorly-trained Russian conscripts can only delay eventual defeat.

Nevertheless, Putin has doubled down on his calamitous war by announcing a partial mobilization aimed at conscripting 300,000 (and possibly many more) troops for Russia’s increasingly depleted military. He also has ordered missile, manned bomber and drone attacks on major Ukrainian cities and infrastructure.

Unmanned aerial vehicles large and small continue to play a dominant role in this terrible conflict. Missile-armed unmanned combat air vehicles (UCAVs) and loitering munitions have shown their value. Russia has been running low on conventional stand-off range missiles it can only build in single digits monthly, prompting it to purchase hundreds of “kamikaze drones” from Iran and fly them into action; Starting in September, at least 200 have carried out attacks on Kviv, Odessa and beyond. Also disruptive has been the adaptation of cheap, commercial off-the shelf (COTS) drones by both sides to execute surprisingly effective tactical-range strikes and, even more lethally, to acquire targets for artillery fire of unprecedented precision and speed.

This has resulted in an indirect-fire-centric battlefield, in which even main battle tanks are more likely to be knocked out by drone-assisted howitzers than by anti-tank missiles, air strikes and enemy tanks.

Events are unfolding rapidly on the UAS front. In mid-October, Ukrainian President Volodymir Zelensky claimed Russia plans to order 2,400 more loitering munitions, indicating a desire to sustain a campaign of strategic attacks on Ukrainian cities and civilian infrastructure—even as both sides have become much more effective at destroying them.

ELECTRONIC WARFARE VS. DRONES

While counter-drone air defense underperformed in the war’s first weeks, by late spring both sides’ UAVs began to suffer heavy attrition. A study published in July by Jack Watling and Nick Reynolds of the UK’s RUSI think tank found that a Ukrainian drone averaged just 7 days of combat activity before being lost.

That attrition imposed difficult choices for Ukrainian commanders. As the study states: “…many Ukrainian units are forced to choose between having a live feed from their UAVs and thereby risking a high likelihood of losing the platform or sending UAVs out on pre-set flight plans and analyzing the images they take on their return to a pre-set location.”

Of course, fully automated flight plans assisted by inertial navigation systems (INS) to compensate for Russian GPS-jamming allow UAVs to operate independently of a command signal—but without the benefit of situational reactivity. Overall, the resulting intel is less useful, particularly for mobile targets, and processing hours of recorded footage is time consuming.

Thus, Ukrainian command center operations have become dependent on windows of opportunity where/when Russian electronic warfare (EW) is weak. Reliance on the Starlink satellite network, so far impervious to Russian jamming, has enabled Ukraine units to reliably relay targeting data to friendly forces.

The Oryx blog found images confirming destruction of at least 14 Bayraktar TB2 combat drones, and the loss or capture of eight Ukrainian-built A1-SM Fury and three Leleka-100 ISR drones by early September.

Russian tracked R-330Zh Zhitel and phone-tower mounted Pole-21 systems provide near-constant, generalized area jamming affecting drones and GPS. More targeted EW attacks against Ukrainian drones are executed by a variety of tactical jammers, from the Repellant-1 truck (allegedly only effective within 1.6 miles) to space-age counter-UAS guns.

But according to the RUSI study, Russia’s most important tactical counter-UAS system is the truck-mounted Shipovnik-Aero tactical jammer, which can engage two drones simultaneously and also suppress local communications networks. When an Aero detects a drone, it takes about 25 seconds to classify the type, then employs an appropriate transmitter to disrupt its command frequency along a 3-degree azimuth. Sometimes, it can even redefine the drone’s “home base” to a point under Russian control, enabling capture of the UAV.

Russia first deployed Shipovnik-Aero in Ukraine in 2016. By the summer of 2022, according to Watling and Reynolds, “their presence has become widespread, limiting the airspace that Ukrainian UAVs are able to penetrate and monitor,” though its 40-minute deployment time offers an Achilles’ heel.

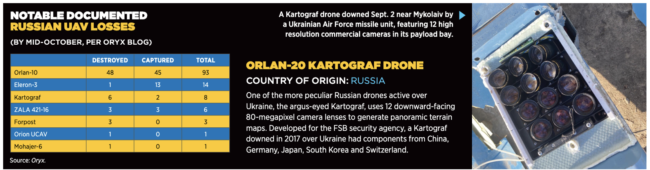

On the Russian side, photos show loss of well over 100 mostly reconnaissance drones. Actual total losses for both sides surely number in the hundreds, particularly factoring in smaller copter-style UAVs.

A high ratio of captured drones reveals Russian units too are feeling the sting of electronic warfare, with some operators concluding it was safer to simply hover drones above friendly positions to avoid losses. One video released by a Russian military journalist shows a drone team helplessly looking through a video feed as Ukrainian forces hijack its drone. Their position compromised, they hastily decamp to avoid attack.

What can operators do to curb the counter-drone war? Samuel Bendett, an expert on AI and unmanned systems advising the Russia Studies Program at the Center for Naval Analyses, wrote to me: “Both sides are now reworking their drone software to make quadcopters more EW-resistant and sharing battlefield lessons with other operators, especially on avoiding the other sides’ defenses.”

However, quantitative solutions may be more practical than qualitative ones. “In the end, many EW systems cannot be overcome,” Bendett continued. “The simplest method is to replace lost drones, especially cheaper quadcopters.”

Of course, UAVs are also responsible for a substantial share of EW and air defense systems destroyed, using both direct attacks or by calling in and adjusting indirect fires.

Kinetic air defenses, including costly ground-based air defense missiles, are also accounting for many drone losses. Though many drones cost less than the missile fired at them, the potential destruction an accurate artillery strike called in by a drone could wreak makes it worth using whatever means at hand.

Still, the importance of fielding more diverse and cost-efficient counter-drone weapons is clear. Drones have been destroyed by small arms fire, flak, cannons and jet fighters. Supporters of Ukraine are sending laser-guided rockets and vehicle-mounted jammers. Soldiers from both sides are employing counter-UAS guns often obtained outside regular military procurement channels.

As small UAVs can be difficult to detect compared to manned aircraft, combat experience from this war arguably makes a case that even-smaller tactical formations such as infantry companies should integrate lightweight radars and EO/IR sensors to more reliably detect nearby UAVs without depending on external air defense attachments.

LOGISTICS AND TRAINING FOR THE FUTURE DRONE FORCE

Despite—or because of—massive attrition, the demand from frontline troops for more drones is voracious. Russian military bloggers have fumed at the inadequate numbers of Orlan-10 ISR drones—reportedly often no more than one per battalion—the loss of which can be crippling.

Russian forces are also heavily reliant on civilian donations due to a procurement gap pertaining to smaller, shorter-range ISR drones. A list circulating on Russian social media of suggested gear for newly conscripted soldiers recommends bringing a drone along with an extra pair of socks.

The government of Buryatia (a minority region in Russia disproportionately represented among frontline soldiers) spent $3.4 million of its own funds to provide drones and other equipment to its soldiers, reflecting popular awareness that the Russian military is failing to adequately equip them.

Russia’s military is taking steps to procure more UAVs, but also is suffering a shortage of drone pilots. Between September 1-5, veteran drone operators assembled at Lake Ilmen, Russia, for the Dronnitsa conference to share best practices toward the ultimate goal of creating a professional instructor corps and developing a standardized training curriculum. Moscow has announced measures to scale up drone production, as well as to integrate education on using drones into school curricula.

A few days earlier, Ukraine had held its own “hackathon,” gathering 150 operators, engineers and programmers in Kyiv to share exchange ideas on leveraging Ukraine’s sizeable tech sector to improve effectiveness of unmanned operations.

These moves show both sides recognize how even small civilian-class drones have become a key component of military power, and that governments must standardize training and procurement of capabilities that heretofore had evolved organically from improvisations in the field.

LOITERING MUNITIONS: THE BIGGER, THE BETTER?

Loitering munitions (or kamikaze drones) have taken on an expanding role as both Ukraine and Russia turn to them to perform penetrating strikes—operations both sides consider near-suicidal for manned aircraft due to ground-based air defense.

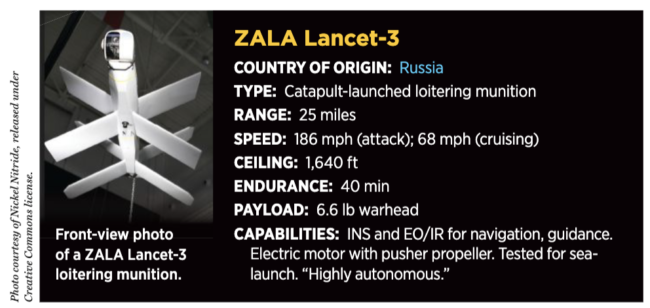

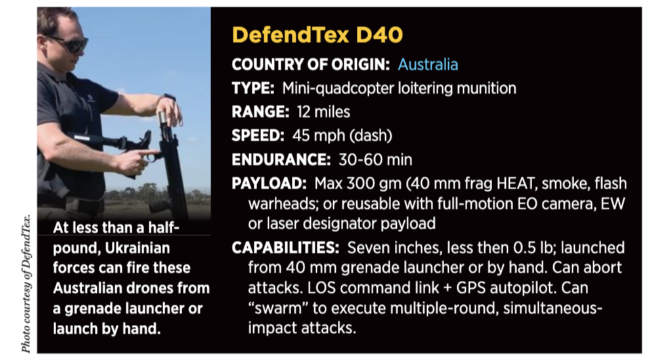

Media showing the effective use of smaller loitering munitions early in the war remains sparse, however. The few videos of Switchblade-300s given in the hundreds to Ukraine show them picking off individual soldiers. Russia’s delta-winged ZALA KUB displayed poor accuracy and lacked the punch to reliably disable a towed howitzer.

But a caution: “Limited video evidence of their use,” Bendett said, “does not mean that such loitering drones are not used on a larger scale.”

During the summer, Russia began employing the newer, missile-like ZALA Lancet-3 with a larger warhead to greater apparent affect. Recordings show Lancet-3s ramming into towed howitzers, on-the-move self-propelled artillery and vans, entrenchments and even a Bayraktar radio repeater tower.

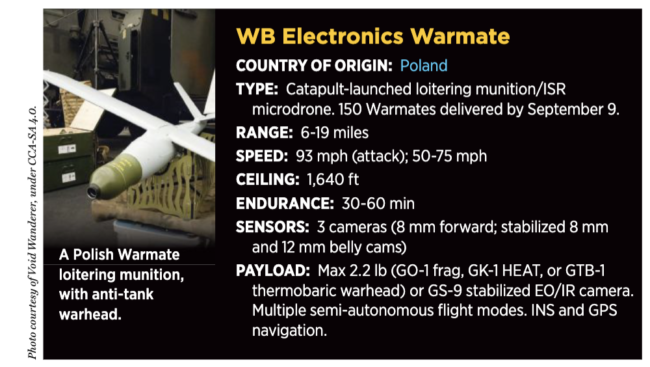

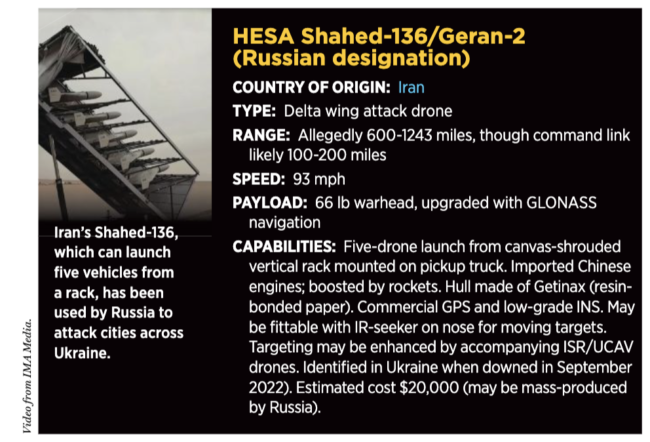

Then, in September, Russia began deploying Iranian-built Shahed-136 munitions (redubbed the Geran-2) to some success according to the commander of Ukraine’s elite 92nd Brigade, who told the Wall Street Journal that in just a few days Shahed-136s (see “HESA Shahid” box) destroyed four self-propelled howitzers and two APCs. Older Shahed-131s loitering munitions (smaller but otherwise similar to Shahed-136s) were also apparently transferred.

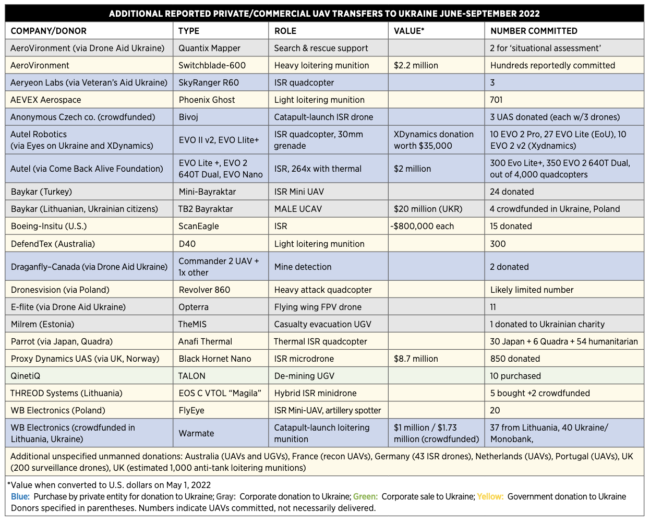

Meanwhile, Ukrainian forces are reportedly satisfied with the Polish Warmate loitering munition (see “Warmate” box). They’ve received a small number of Switchblade-600s, which have required time to enter production. Kyiv has also obtained hundreds of secrecy-shrouded, backpackable Phoenix Ghost loitering munitions. Ukrainian presidential adviser Oleksii Arestovysch, in July, ascribed a 60% kill rate to the “back-packable” munition.

In October, Ukraine debuted the recoverable RAM-II munition derived from the Leleka-100, recorded destroying an Osa air defense vehicle. Ukrainians have also employed first-person-view racing drones, and their specialized user goggles, as loitering munitions capable of attacking targets inside buildings.

Clearly, militaries should field a tiered mix of loitering munitions ranging in cost, range and hitting power, with at least one “medium” option that can be used cost-efficiently for tactical strikes on artillery and armored vehicles. Such munitions are particularly intriguing when they can be built at a similar or lower price than, say, a Javelin missile ($80,000+ not including launcher) or Excalibur artillery shell ($112,000 per).

RUSSIA’S IRANIAN DRONE ATTACK

Iran deployed its first crude bomb-toting UCAVs in combat in the 1980s. Today, it fields a broad variety of UAVs, UCAVs and micro-missiles produced by rival manufacturers. Tehran has used these to project power over the Persian Gulf and Syria, and to arm overseas allies like Hamas, Hezbollah and Houthi insurgents in Yemen. According to posts by military aviation historian Tom Cooper, Iran’s drones, sensor turrets and munitions have developed considerably since 2016, thanks to technology transfers from China.

As Russia’s UCAV capability via the Orion platform only entered service in 2021, this July Moscow looked to quickly procure more combat and ISR drones from Iran, possibly in exchange for Su-35 jet fighters. The first Iranian drones were delivered mid-August, with Russian personnel training in Iran to operate the UAVs.

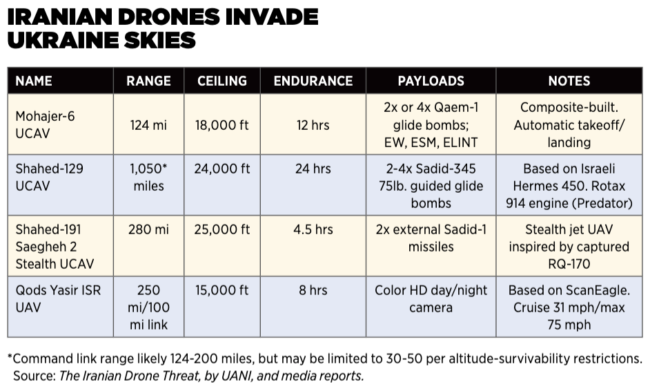

Then, on October 8, an estimated 24 Shahed-129 UCAVs and Shahed-136 kamikaze drones based in Crimea and Belarus were employed on targets across Ukraine, the drones possibly assisting with missile targeting. Ukraine’s military claims 12 UAVs were downed by air defenses, including nine of 12 Shahed-136s.

The three runway-using Iranian UCAVs identified as being delivered to Russia have seen prior combat use and are equipped with the requisite electro-optical sensor turrets and small guided missiles in laser, IR and TV-guided variants (see “Iranian Drones Invade Ukraine Skies” box).

However, intelligence sources cited by the Washington Post suggest Russia has been “not satisfied” with the Iranian UCAV’s for experiencing “numerous failures,” echoing reports that Mohajer-6s imported by Ethiopia in 2021 performed poorly. On Sept. 23, Ukraine shot down a Mohajer-6 UCAV over water, recovering it intact with its Qaem-5 (or Ghaem) TV-guided glide bomb, sensor turret and Austrian-built Rotax engine. Furthermore, Russian drone footage seemingly betrays the use of Iranian Qods-Yasir ISR drones, the “Iranian ScanEagle.” Qods was test-converted for use as a kamikaze drone, but its operational use in that capacity is unclear. Russia allegedly plans to buy the larger Arash-2 loitering munition from Iran.

UCAVS OVER UKRAINE

Both Russia and Ukraine continue to employ UCAVs in combat, the latter more prominently, with a decisive impact on Ukraine’s siege of the Russian garrison on Snake Island and penetrating attacks onto annexed Crimea or Russian soil. These raids have occasionally caused spectacular damage, appealingly with little loss of life, but weakening Putin politically.

However, density of air defenses and electronic warfare environment has prevented unrestricted use of UCAVs, and neither Ukraine’s Bayraktars nor Russia’s Orion and Forepost-R drones have wreaked the mass destruction achieved against Armenian and Syrian ground forces in 2020. Both sides’ UCAV fleets are too small to “trade off” against more numerous air defenses in a battle of attrition. Ukrainian fighter pilots have evenargued that procurement of more UCAVs is pointless under these circumstances, though they may have a professional bias.

Nonetheless, both sides can and do accept greater risks with UCAVs than with their combat aircraft. Furthermore, Ukraine has conducted standoff strikes on Russian air defenses using HIMARS, Neptune and HARM missiles to create windows of opportunity to deploy UCAVs in its ongoing Kherson offensive.

Russia, arguably, could benefit from UCAVs even more; their combination of long-endurance ISR and strike capability and expendability compared to manned aircraft would make them an ideal platform for hunting down and destroying precise western artillery and GPS-guided rocket systems (HIMARS, MARS) that have been relentlessly destroying Russian ammunition depots and HQ buildings. In practice, though, Russia has not provided convincing evidence that its UCAVs have located and destroyed any HIMARS systems, perhaps due to Ukraine’s effective use of wooden decoys to absorb Russian attacks.

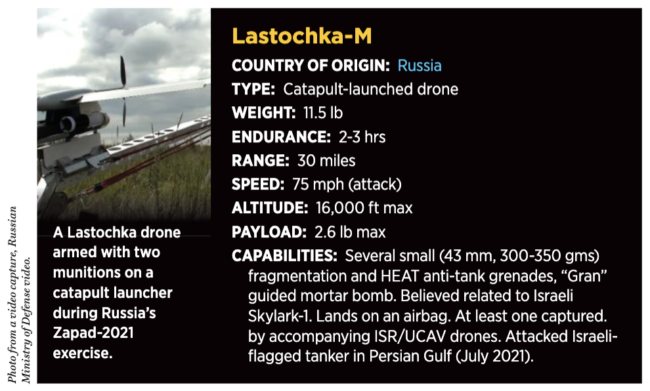

Over the summer, Russia developed a method to arm Orlan-10 ISR drones with grenades, and began deploying a new small Lastochka-M attack drone dropping unguided munitions. By 2023, Russia hopes to ramp up production of Orion UCAVs, and install satellite links and develop autonomous air-to-air refueling technology to extend the range of its drones.

✓✓ GREY EAGLE: TOO SENSITIVE FOR UKRAINE

Washington would like to give Ukraine four Hellfire missile-armed General Atomics MQ-1C Grey Eagles, the U.S. Army’s in-house UCAV, with greater capability than the Bayraktar. The transfer has been under review since June, however, because of concerns Ukraine’s military might be unable to properly support the system, and that Russia might acquire sensitive technologies from downed MQ-1Cs. General Atomics has proposed an intense five-week cram course (12 hours a day, no days off) to rapidly familiarize Ukrainian operators and technicians.

AI is another edge technology that has been used in Ukraine for collation of battlefield intelligence. But when it comes to unmanned systems, Rita Konaev, a military AI expert at the Center for Security and Emerging Technology (CSET), noted in a tweet: “It’s hard to tell whether these are in fact autonomous or automated, and if they’re even being used; or are they mostly if not fully remotely operated.”

WAR OF THE CAMERA DRONES

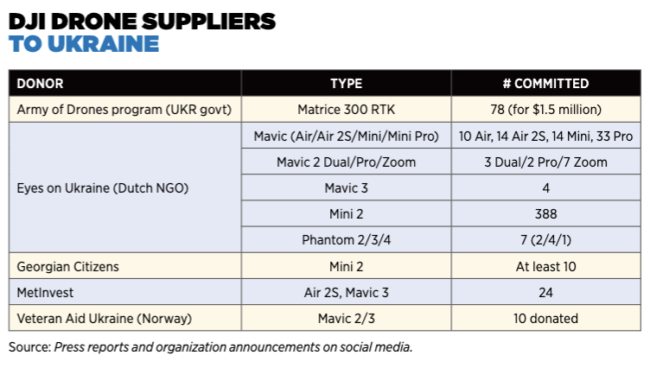

Despite producing various indigenous fixed-wing drone platforms, both Ukraine and, increasingly Russia, are heavily dependent on purchase or donation of UAVs large and small from overseas—whether through privately crowdfunded drives, transactional arms sales and, in Ukraine’s case, free-of-charge government-to-government military aid.

Most numerous are cost-efficient DJI camera drones built in China. Wartime demand has reportedly caused the price of drones to at least double in Russia, particularly after DJI halted sales to Russia and Ukraine in April. Nonetheless, the Russian embassy in China praised the DJI Mavic on social media as “a symbol of modern warfare.” Autel Robotics’ EVO series of drones (U.S.-based but Chinese-owned) are also used prolifically by Ukraine.

Moscow has its ways of circumventing bans and sanctions. “Russians are specifically instructing volunteers to procure DJIs at different online and physical marketplaces in eastern Europe and Asia,” Bendett explained—particularly Belarus, and southeast Asia. “With so many DJI Mavics sold all over the world, there is a massive supply that can potentially flow to the front.”

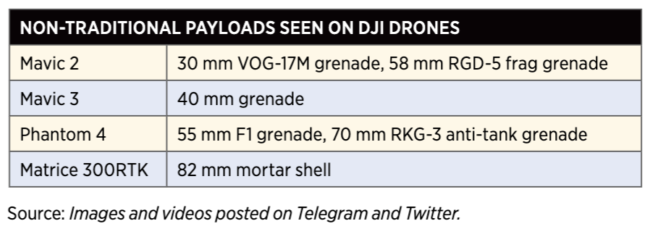

Commercial quad- and octocopters have also proven readily convertible into precision strike weapons. Videos posted by both Ukrainian and Russian soldiers continue to display outrageous feats of gravity bombing, dropping tiny antitank grenades through the open hatches of main battle tanks and other vehicles with absurdly destructive results. In some cases, the attacks target abandoned vehicles, but their destruction is nonetheless useful in places where they can’t be safely recovered.

Just as Ukraine’s military learned and improved on drone tactics Russian separatists employed in the 2014-2015 war, videos are showing Russia copying Ukraine’s improved methods.

Massive use of DJI products could theoretically be compromised should the company, or state regulators, attempt to impose geographic locks. However, Ukraine has reportedly developed a hack to “reflash” DJI drones and remove safety software Russia exploited in the past to locate and disable drones or attack their operators.

Ukraine and Russia could produce similar camera drones domestically, but production quality, scale and cost-efficiency would likely not be the same, Bendett advised—especially for Russia as it struggles to obtain microelectronics because of international sanctions.

Nonetheless, Russian arms manufacturer Almaz-Antey announced it was testing a self-developed quadcopter with 90% domestic parts made of lightweight polymers and carbon fibers that could eventually serve as a “Russian DJI.”

UNMANNED LAND AND SEA VEHICLES

To supplement its Uran-6 de-mining vehicles, Russia has begun using the remote-controlled 45-ton Prokohd-1 UGV, a disarmed T-90A tank equipped with KTM-7 or -8 mine-rollers—possibly the heaviest operationally deployed UGV so far. Ukraine, meanwhile, is reportedly deploying the Roomba-like Temerland GNOM kamikaze mine. Directed via a quadcopter, it’s designed to roll under armored vehicles and detonate a TM-62 anti-tank mine. A machine-gun-armed variant of GNOM may see patrol use, while Russia says it’s preparing a 3-ton Marker 2 UGV for eventual combat deployment in Ukraine.

At sea, around two dozen mostly unspecified UUVs and USVs, donated to Ukraine by the U.S., U.K. the Netherlands and Germany, play a quiet but strategically high-stakes role mitigating risks from mines or clandestine sabotage attacks on Ukraine’s grain shipping.

Furthermore, on September 21, a novel USV ran aground near Russia’s major naval base at Sevastopol, in Crimea. According to submarine expert H.I. Sutton, the stealthy (median radar cross-section around 0.6 sqaure meters) USV was likely Ukrainian and intended for an explosive kamikaze attack. If Ukraine manages to use UUVs/USVs to damage valuable Russian naval assets in port, that could further weaken the Russian Black Sea Fleet’s posture after the loss of flagship missile cruiser Moskva.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment