-- the first one is microbial

-- the second is racial and

-- the third geopolitical

Author Natalie Koch Koch teaches us to see deserts anew, not as mythic sites of romance or empty wastelands but as an "arid empire," a crucial political space where imperial dreams coalesce.

A revelatory new history of the colonization

**Longlisted for the 2023 Cundill History Prize**

The iconic deserts of the American southwest could not have been colonized and settled without the help of desert experts from the Middle East.

As Natalie Koch demonstrates in this evocative, narrative history, the exchange of colonial technologies between the Arabian Peninsula and United States over the past two centuries ---- from date palm farming and desert agriculture to the utopian sci-fi dreams of Biosphere 2 and Frank Herbert's Dune ---- bound the two regions together, solidifying the colonization of the US West and, eventually, the reach of American power into the Middle East.

EPISODE VIDEO

SOURCES

- Brian Beach, professor of economics at Vanderbilt University.

- Marc Johnson, professor of molecular microbiology and immunology at the University of Missouri School of Medicine.

- Amy Kirby, program lead for the National Wastewater Surveillance System at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

- Natalie Koch, professor of geography at Syracuse University.

RESOURCES

- “Tracing the origin of SARS-CoV-2 omicron-like spike sequences detected in an urban sewershed: a targeted, longitudinal surveillance study of a cryptic wastewater lineage,” by Martin Shafer, Max Bobholz, Marc Johnson, et al. (The Lancet Microbe, 2024).

- Arid Empire: The Entangled Fates of Arizona and Arabia, by Natalie Koch (2023).

- “How a Saudi Firm Tapped a Gusher of Water in Drought-Stricken Arizona,” by Isaac Stanley-Becker, Joshua Partlow, and Yvonne Wingett Sanchez (The Washington Post, 2023).

- “Arizona Is in a Race to the Bottom of Its Water Wells, With Saudi Arabia’s Help,” by Natalie Koch (The New York Times, 2022).

- “Water and Waste: A History of Reluctant Policymaking in U.S. Cities,” by Brian Beach (Working Paper, 2022).

- Water, Race, and Disease, by Werner Troesken (2004).

- COVID Data Tracker: Wastewater Surveillance, by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

25 December 2015

Hi Jolly! A Syrian On A Camel Spotted Here In Arizona

How fast the political backlash and fears for safety strike out from Arizona Governor Ducey and both 5th District Congressman Matt Salmon and 9th District Congresswoman Kyrsten Sinema calling for actions restricting immigration from Syria and The Middle East.

Yet "once upon a time and not so long ago" what was then the United States in the mid-19th century - oops! this territory was once part of The Confederacy - decided to establish a Camel Military Corps involving 77 dromedaries imported from The Ottoman Empire, along with six Turks and a Syrian named Hadji Ali for military purposes and reconnaissance.

|

| Hi Jolly Monument in Quartzite [Tyson's Well] |

The story of Hi Jolly began in 1855 when Secretary of War Jefferson Davis was told of an innovative plan to import camels to help build and supply a Western wagon route from Texas to California. It was a dry, hot and otherwise hostile region, not unlike the camel's natural terrain in the Middle East.

In a report from June 1857 Lieutenant Edward Beale, leader of one of the expeditions, indicated the great advantages of camel travel. The camels, he noted, did not need grass but could eat all forms of desert brush and managed for days without water. He reported that “they are the most docile, patient, and easily managed creatures in the world,” even in the trying conditions of the harsh American southwest.

Readers can look into more details here in an account called "Strangers in a Strange Land: Hi Jolly and the U.S. Camel Corps" on the History Bandits website.

It begins with this: In Quartzsite, Arizona, an odd monument stands just off Highway 95. Erected in 1935, it is inscribed as “the last camp of Hi Jolly.” This marker, crowned with a copper camel, seems out of place in the desert of western Arizona. It stands as a testament to the bizarre experience of a group of strangers brought to the American west in the mid-19th century.

Official Arizona historian Marshall Trimble has some important details to add in this article

from Russia Today RT.com

Other details readers might find interesting can be found here

18 September 2021

Influence-Maker Jordan Rose: Pinal has Water. . .What She Doesn't Disclose Her Clients are Real Estate Developers

How Pinal County defies the odds to increase development in a drought

By Madelaine Braggs | Rose Law Group Reporter

With a massive influx of new out of state residents filling Phoenix metro vacancies, Arizona desperately needs housing development to grow in Pinal County, but with no groundwater.

HOLD ON!

Here's a post farther down on September 5, 2019 from Saints Holdings on Twitter if readers of this blog are curious what the Saint's holding companies are planning to create between Phoenix and Tucson around Casa Grande and Coolidge and Florence > a new "inland port", much similar to the same thing in-the-works in Utah. . . it certainly looks likes they are tending to now privatize water-rights just when a federal Drought Emergency Contingency Plan has been activated. When big deals like the sale of 'obsolete water-rights' on thousands of acres that would be just dirt without it, there's always scandals that surface somehow taking a cue from an earlier extract . . .

Here's a post farther down on September 5, 2019 from Saints Holdings on Twitter if readers of this blog are curious what the Saint's holding companies are planning to create between Phoenix and Tucson around Casa Grande and Coolidge and Florence > a new "inland port", much similar to the same thing in-the-works in Utah. . . it certainly looks likes they are tending to now privatize water-rights just when a federal Drought Emergency Contingency Plan has been activated. When big deals like the sale of 'obsolete water-rights' on thousands of acres that would be just dirt without it, there's always scandals that surface somehow taking a cue from an earlier extract . . .It seems like an impossible task… however, Pinal Partnership is proving that the solutions are here, legislation just needs to get on the same page.

At this week’s Pinal Partnership panel Water Solutions 2.0, moderated by Rose Law Group founder and president Jordan Rose, farmers, former mayors, stakeholders and regulators all gathered to share their expertise. While the situation is daunting, it turns out there is a way to develop through a drought.

I can’t get a new assured water supply determination, what can I do?

“We’re looking at the property and figuring out all the assets that exist in your control that we can leverage to create an assured water supply.”

But it won’t be easy. Questions will arise such as, “Are you located in an irrigation district where we can deliver water? Or can you with your rights? Can we recover that irrigation system and then build and isolate a water system for your subdivision?”

To create a water system to serve a housing development, without new groundwater permits, builders essentially must include an irrigation system and treatment plan that would have to bring water from a resource like the Colorado River, for example. It would have to be funneled somehow into Arizona canals, purified and then into homes

“The federal government has failed to offer a plan that requires all states to make the cuts necessary to save the Colorado from system collapse,” said Stanton, a Democrat.

Stanton may be calling on the federal government to “play a stronger role” now, but he was not seen as very concerned about water preservation when he served from 2012 to 2018 as the Mayor for the city of Phoenix, or during his eight years on the Phoenix City Council.

Officials in Phoenix have been often criticized for failing to involve all stakeholders in water conservation plans and for pushing “publicity friendly” ideas which do not adequately address long-term planning needs or economic realities.

Another politician being called out for his response to the Colorado River cuts is U.S. Sen. Mark Kelly, who is now demanding the Department of Interior make long-term solutions “an urgent priority,” despite the fact Arizona’s water future has been a top priority for state Republicans for several years.

Earlier this year, Gov. Doug Ducey signed Senate Bill 1740 which provides a $1 billion investment for projects providing additional water for the state. In addition, the governor is currently accepting applications for the Water Infrastructure Finance Authority Board created as part of the legislation.

11 November 2020

Are The Cows Already "Outta-The-Barn" In Pinal County? > Pinal County will intervene in sale of Johnson Utilities

There's definitely "Something-In-The-Water" - in the murky history and double back-handed dirty money deals running through the pipelines of politics in Pinal County. Some people crossing county lines in Mesa and Queen Creek don't exactly have 'clean hands' to show for all their efforts.

To learn the purchase price, the county will need to approve a non-disclosure agreement, . .Johnson Utilities customer John Dantico strongly urged the board to intervene, as the county is the closest government entity for more than 100,000 people whose quality of life will be affected for decades to come, he said.

“Everyone is in favor of EPCOR acquiring Johnson Utilities but there are important issues that need to be reviewed in the hearing like how EPCOR intends to provide service to areas that are still subject to a moratorium and how much this acquisition will impact ratepayers with future rate increases.

Comment by Deal--Maker Court Rich, Rose Law Group Co-Founder

(Disclosure: Rose Law Group represents landowners and homebuilders working with the ACC to find a utility solution in the Johnson Utilities service area.)

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

RELATED CONTENT ON THIS BLOG

25 May 2019

Troubled Waters Here In The East Valley: Who Ya Gonna Call?

It's not just about Johnson Utilities in Queen Creek and the newly-incorporated city of San Tan Valley. There

22 July 2021

Arizona "Ground-Zero" >>

Feeding-The-Blob: Mesa's Suburban Sprawl /

De-Facto Segregation /

Sub-Division Cadence @ Gateway

“Isn’t it beautiful?” asked Megan Santana, whose own home is currently under construction, as we walked toward the back of the community center, which has a large green lawn. “You feel like you’re on an island resort.”

Megan Santana and her son, Malachi, stand in front of their future home in the Cadence subdivision in Mesa, AZ. There’s such high demand at Cadence that Santana had to win a spot in a lottery before she could purchase a home. Photo credit:

Santana, who is 34, moved to the Phoenix area last October from Texas with her 9-year-old son, Malachi, and her business partner, Alyssa Bell. Tanned and fit, with long dark hair that hangs in loose curls, Santana grew up in rural Virginia but moved to Florida when she was 22, hoping to settle down and enjoy the warm weather. Instead, the yearly hurricane season caused her so much stress that she moved to Dallas. From a natural disaster standpoint, though, Dallas was not much better: The city, which lies in a so-called Tornado Alley, experiences frequent severe storms. Santana began researching states that had few natural disasters, and Arizona turned up at the top of the list.

Six months ago, Santana joined the hundreds of thousands of people who have moved to the greater Phoenix area in recent years looking for affordable homes, sunshine, and warm winters. The pandemic has only intensified that trend, with home sales increasing by nearly 12 percent in 2020. There’s just one problem: The region doesn’t appear to have enough water for all the planned growth.

In 2017, Phoenix became the fifth-largest city in the US, a sprawling “megalopolis” of almost 5 million people that’s also known as the Valley of the Sun. A few outlying “mega-burbs” like Buckeye and Goodyear to Phoenix’s west and Queen Creek to the east have annexed large amounts of land and are themselves some of the nation’s fastest-growing cities. By 2040, the region’s population is expected to reach more than 7 million, despite its limited and shrinking water supply.

Even though the effects of climate change are intensifying throughout the Southwest, people keep moving here — to the hottest, driest part of the country. Unlike wildfires or hurricanes, a diminishing water supply is a slow-moving, mostly invisible crisis. But if current growth rates continue, in roughly a decade it will be impossible to ignore. That raises questions about whether policies and attitudes that encourage maximum growth are sustainable. Many of the area’s rapidly expanding suburbs lack access to the water necessary for all the growth they are planning, said Mark Holmes, Goodyear’s water resources manager from 2012 to 2018. Unless they can develop significant new water supplies, he said, “the alternative is something they don’t want to think about.”

Roofers work on a house in the Ghost Hollow Estates on the northeastern edge of Casa Grande, AZ. Photo credit:

There’s truth to these assessments:

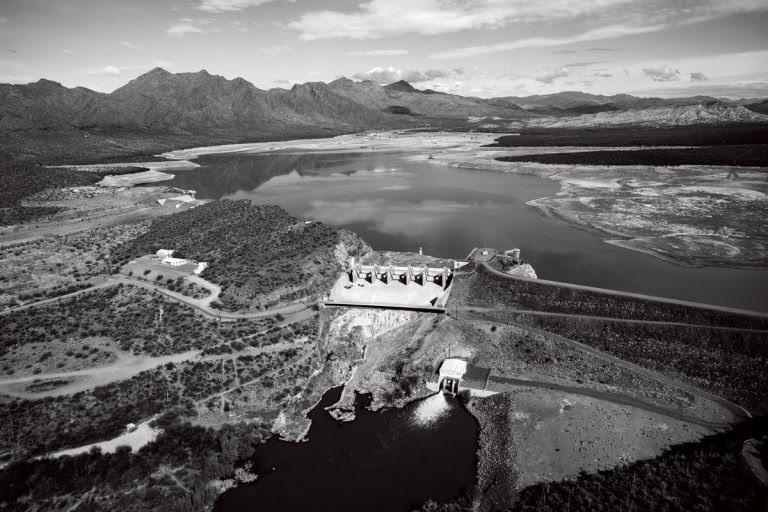

The Valley of the Sun receives less than 8 inches of rainfall each year. Most of the valley’s water supply comes from the winter snowpack in distant mountains, which melts and flows through a vast system of dams, reservoirs, and canals. Two major watersheds are involved: The Central Arizona Project (CAP) diverts water from the Colorado River, 300 miles away, and the Salt River Project (SRP) draws from the Salt and Verde rivers, north of Phoenix.

- There are two other water sources: groundwater, which is pumped from the aquifer below, and a small but growing amount of treated wastewater, accounting for an estimated 5 percent of the water supply statewide. Every municipality has a different mix of water supplies with varying degrees of reliability. Urban Phoenix, for instance, has diversified and carefully managed water supplies, while many of the newer outer-lying suburbs are much more dependent on a single source, according to the City of Phoenix Water Services Department.

In the early years of Phoenix’s growth after World War II (when air conditioning became widely available) much of its water supply came from pumping groundwater. But rapid declines in aquifer levels in the 1960s and 1970s pushed state lawmakers to pass the Groundwater Management Act in 1980. The law created “Active Management Areas,” which required developers and municipal water providers to obtain permits from the Arizona Department of Water Resources confirming that they had 100 years of “assured water supply” for new homes.

Originally, that assured water supply came primarily from the Salt River Project or the Colorado River, but in 1993, the state paved a way to build new homes served only by groundwater, allowing housing development to spread into the outer reaches of Phoenix and Tucson. To do that, legislators created the Central Arizona Groundwater Replenishment District (CAGRD), an entity tasked with replacing pumped groundwater by finding renewable water supplies and injecting that water back into the aquifer.

The Central Arizona Project canal had just been completed, and the Valley of the Sun was flush with new surface water deliveries from the Colorado River. Developers and municipalities that lacked an assured water supply could enroll in the CAGRD, which in turn, charged a fee for replenishing the groundwater they used. They did so with surface water acquired by various means, including the purchase of excess CAP supplies or leasing Colorado River water from tribes.

A lateral canal brings water from the Central Arizona Project (CAP) canal system to agricultural land near Casa Grande, AZ. Photo credit: Roberto (Bear) Guerra / High Country News

Meanwhile, unrelenting drought and years of rising temperatures due to climate change have pushed the long-overallocated Colorado River to the brink, making it increasingly difficult for the CAGRD to find new renewable water supplies to meet its long-term obligations. This, in turn, caused the CAGRD’s replenishment fee to soar from $154 per acre-foot in 2002 to $742 per acre-foot in 2021.

A 2019 report published by the Kyl Center warns that in the long term there likely won’t be enough surface water available from the Central Arizona Project to replenish the groundwater used by all the homes currently planned for the Phoenix suburbs. Although enrollment in the CAGRD has slowed in recent years, that amount is expected to total 102,000 acre-feet annually 100 years from now.

Buckeye’s municipal planning area, for instance, covers 642 square miles — larger than the size of Phoenix — but it’s currently only 5 percent built out. The city has approved 27 master-planned housing developments that would bring an additional 800,000 people by 2040 — despite a water supply that’s almost entirely dependent on groundwater.

Photo credit: Luna Anna Archey / High Country News

If the city cannot provide an assured water supply, those future subdivisions will have to enroll in the CAGRD, which will have to find 127,000 acre-feet of additional surface water annually to replenish the aquifer, said Sarah Porter, director of the Kyl Center and co-author of the Assured Supply report. That’s more than four times the current replenishment obligations for the entire CAGRD. “We’re not thinking enough about how to stop all this from happening,” Porter said.

“I think that the ability of the Valley of the Sun to exist 100 years into the future depends so closely on our ability to steward our groundwater today, and I really see CAGRD as subverting that stewardship.”

RELATED CONTENT ON THIS BLOG

Featured in the report is Kathryn Sorensen, director of Phoenix Water Services. She’s proud of the work she has done since she was appointed in 2013 — before that she served four years as head of Mesa, Arizona’s water department.

On her desk sits a crystal ball, a joke gift that she says she wishes was real.

Much of conservative Arizona is in denial about what the potential drying of the West may mean, if they recognize it at all.

An Info-Graphic: Half-Full or Half-Empty?

An Info-Graphic: Half-Full or Half-Empty?

Denials aside, and meeting last-minute deadlines not met by the Arizona State House, let's step back from the political-wranglings in Phoenix of the most precious commodity here in the desert: Water.

There's a new report published today from the Yale School of Forestry & Environmental Studies:Part IV of Crisis On The Colorado: ". . . The fate of the Hohokam holds lessons these days for Arizona, as the most severe drought since their time has gripped the region. But while the Hohokam succumbed to the mega-drought, the city of Phoenix and its neighbors are desperately scrambling to avoid a similar fate — no easy task in a desert that gets less than 8 inches of rain a year. . . "

The reports cites a two-decade drought earlier in the history of the Salt River Valley:

"The Hohokam were an ancient people who lived in the arid Southwest, their empire now mostly buried beneath the sprawl of some 4.5 million people who inhabit modern-day Phoenix, Arizona and its suburbs. Hohokam civilization was characterized by farm fields irrigated by the Salt and Gila rivers with a sophisticated system of carefully calibrated canals, the only prehistoric culture in North America with so advanced a farming system.

Then in 1276, tree ring data shows, a withering drought descended on the Southwest, lasting more than two decades. It is believed to be a primary cause of the collapse of Hohokam society. . . "

Supplying enough water to sustain the Suburban Sprawl of a Metro Region this size in the desert has long been controversial.

. . . as Phoenix and its neighbors continue their unrelenting sprawl — Arizona’s population has more than tripled in the past 50 years, from 1.8 million in 1970 to 7.2 million today — the state has often been regarded as the poster child for unsustainable development. Now that Colorado River water appears to be drying up, critics are voicing their “I told you so’s.”

_________________________________________________________________________

Featured in the report is Kathryn Sorensen, director of Phoenix Water Services. She’s proud of the work she has done since she was appointed in 2013 — before that she served four years as head of Mesa, Arizona’s water department.

On her desk sits a crystal ball, a joke gift that she says she wishes was real.

". . .in late December, the Phoenix City Council rejected a water rate increase to pay for the infrastructure expansion. The Salt and Gila rivers also may someday be severely impacted by climate change. “They could be affected by a mega-drought,” said Andrew Ross, a sociology professor at New York University and author of Bird on Fire: Lessons from the World’s Least Sustainable City.

“They are in the bullseye of global warming, too.”

________________________________________________________________

Much of conservative Arizona is in denial about what the potential drying of the West may mean, if they recognize it at all. “We’re just starting to acknowledge the volatile water reality,” said Kevin Moran, senior director of western water for the Environmental Defense Fund.

“We’re just starting to ask the adaptation questions.”

Ross, of New York University, argues that the biggest problem for Arizona is not climate change, but the denial of it, which keeps real solutions — such as reining in unsustainable growth or the widespread deployment of solar energy in this sun-drenched region — from being considered.

“How you meet those challenges and how you anticipate and overcome them is not a techno-fix problem,” . . . It’s a question of social and political will.”

_______________________________________________________________

But Alan Jones, the president of Lennar’s Phoenix division, believes those fears are overblown.

> Water use is declining as conservation, treated wastewater, and no-grass landscaping become more prevalent, while putting subdivisions on Arizona’s former agricultural lands creates a net water savings, since growing crops uses more water than residential areas do.

> Plus, in 2018, the CAGRD secured a deal with the Gila River Indian Community, which borders the south side of Phoenix, for up to 830,000 acre-feet of its Colorado River allocation over the next 25 years, starting in 2020. Other Arizona tribes, he added, have large supplies that the CAGRD and municipalities could acquire.

“There’s sufficient water,” Jones assured me, “but at what cost?”

Horseshoe Reservoir on the Verde River is part of the Salt River Project’s extensive infrastructure for supplying water to the Valley of the Sun. Photo credit:

In Pinal County, a rapidly growing rural area just south of Phoenix, the reckoning over future growth has already begun. One day in late March, I met Stephen Miller, the Pinal County District 3 supervisor, in Casa Grande, a town of 55,000. New housing developments have exploded here in recent years. “The farther out you get, the cheaper the land, the cheaper the house,” he said as we drove through town. “That’s what’s caused a lot of sprawl,” he added, quoting an old saying in the building business: “Drive till you qualify.”

Born and raised in the Phoenix area, Miller has the jovial, every-man demeanor of a local politician. A former homebuilder and land developer, he’s watched Pinal County transform from a sparsely populated agricultural region to a booming Phoenix suburb of 500,000 people with an up-and-coming electric car industry. The current housing boom, which followed a down period after the 2008 recession, is unlike anything Miller has seen in 50 years in Casa Grande.

Almost all of Pinal County’s residential water supply comes from groundwater through enrollment in the CAGRD. But in 2019, the Arizona Department of Water Resources updated its groundwater model for the Pinal Active Management Areas and found that there isn’t enough water to meet all the projected demands for 100 years.

These findings led the department to stop approving applications for new 100-year assured water supply certifications for future subdivisions in Pinal County.

“It’s not a panic situation,” Miller told me, when I asked whether the news had worried him. “The good thing is, we’re not out of lots,” he added; developers own thousands of still-undeveloped lots with valid 100-year water supply certifications. Pinal County has enough room to keep adding houses in the short term. In the long run, however, the county is facing a reality that Arizona politicians like Miller are loath to accept.

“People want to make money,” he told me. “That’s what this is all about. To be perfectly frank, there are people who have millions [of dollars] tied up in land holdings in Pinal County whose future hinges on whatever the water policy ends up being. It’s worth almost nothing if there’s no water.”

Tom Buschatzke, director of the Arizona Department of Water Resources, told me that Pinal County is not the only area facing a groundwater deficit. Sooner or later, Arizona’s other active management areas — including the Maricopa County AMA, which includes most of metropolitan Phoenix — will run out of physical groundwater availability to allocate. “Groundwater is finite,” Buschatzke said, noting that the amount of pumping far outstrips the rate of natural replenishment.

>>> He added that many of the Valley of the Sun’s growing suburban cities are not going to be able to prove the physical availability of water necessary for their ambitious plans for growth — and they know it.<<<

“So where will the future renewable water supplies come from? Is it going to come out of agriculture? Or out of a desalination plant in Mexico?” Buschatzke said, citing an ongoing discussion between the US and Mexico about whether to build a desalination facility on the Sea of Cortez. “We’ll have to make some hard decisions,” he said.

With a waiting list for new homes, construction can’t keep up with demand in the Cadence subdivision in Mesa, AZ. Photo credit:

Next year, water levels on Lake Mead, the largest reservoir on the Colorado River, are projected to drop to their lowest levels yet, triggering the first-ever official shortage declaration by the federal government. The declaration will cut Arizona’s Colorado River supplies by a fifth.

“I heard about the decrease in water supply,” Santana said. “It didn’t worry me.”

Like so many Americans, Santana sees homeownership as a path to economic stability for herself and her son. In the Phoenix area, where home prices are still among the cheapest for major US cities, that dream beckons like palm trees and water slides in the desert. “You’re building generational wealth,” she told me.

“Are you moving to Arizona?” Santana’s business partner, Bell, asked me, as we stood a few blocks from Santana’s future home, gazing toward the edge of the subdivision. Beyond her, a strip of grass disappeared into the sand where workers were leveling a vacant lot for the next phase of Cadence homes."

This article was supported by The Water Desk, an independent journalism initiative based at the University of Colorado Boulder’s Center for Environmental Journalism

.jpg)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment