His parents, Rachel Faucette and James Hamilton, were not married when he was born.

James abandoned the family in 1766 and Rachel died in 1768.

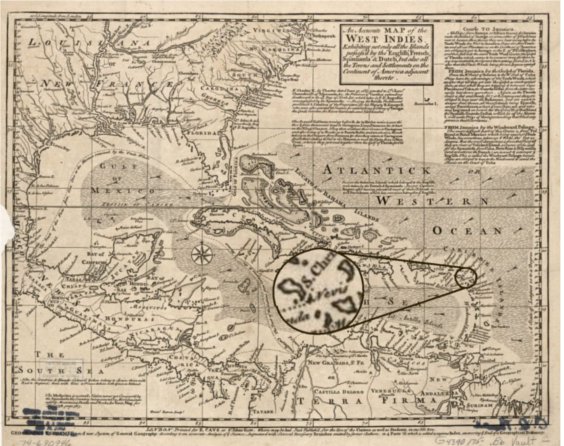

Hamilton spent his adolescence on the Danish possession of St. Croix.

(Scroll down farther for lifelong details)

- He gained passage to the colonies with the power of his pen. ...

- He was Washington's right-hand man in the Revolutionary War. ...

- He was a self-taught lawyer. ...

- He inspired the first U.S. political party. ...

But did you know that Hamilton's involvement with Trinity goes far beyond the churchyard? In his life, he was an active and vital part of the Trinity community. He also rented a pew in the church, although his wife Eliza and the children attended worship more regularly than he did.

Watch a video tour to learn more about Hamilton’s life at Trinity Church.

++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++

Croix. Locals recognized Hamilton’s remarkable intelligence after he published an eloquent letter describing a hurricane that hit the island, and raised money to send him to school in Britain’s North American colonies.

Hamilton arrived in mainland America in late 1772 and initially applied to the College of New Jersey (modern Princeton), but instead attended King’s College in New York City. While in New York, Hamilton became a supporter of colonial protests against British imperial policy. He wrote several pamphlets in 1774 and 1775 attacking the views of outspoken loyalist Samuel Seabury. In 1775, Hamilton drilled with a volunteer company of militia, and was made captain of an artillery company in March 1776. In the American Revolutionary War, he fought at the battles of Kip’s Bay, White Plains, Trenton, and Princeton.

The young captain impressed senior officers in the Continental Army, and William Alexander (Lord Stirling) even asked Hamilton to serve as his military aide. On January 25, 1777, the Pennsylvania Evening Post posted an advertisement: “Captain Alexander Hamilton, of the New-York company of artillery, by applying to the printer of this paper, may hear of something to his advantage.”1 This referenced General George Washington’s decision to invite Hamilton to his military staff, which Hamilton accepted, making him a lieutenant colonel. For the next four years, Hamilton was one of Washington’s most valued staff members, and had a variety of responsibilities, including writing letters to Congress, state politicians, and other Continental Army officers.

Washington and Hamilton from Mount Vernon on Vimeo.

While Washington’s aide, Hamilton wed Elizabeth Schuyler, on December 14, 1780. She was the daughter of Philip Schuyler, who had served as a major general in the Continental Army and was one of the wealthiest men in New York. Hamilton left Washington’s staff in March 1781 after a dispute with the general and out of frustration with his lack of field command. Washington ultimately granted him a field command, and on October 14, 1781, Hamilton led the successful assault of Redoubt 10 during the Siege of Yorktown, which contributed to the surrender of General Lord Charles Cornwallis.

Alexander Hamilton, by Alonzo Chapel. Courtesy Gilder Lehrman.

Following Yorktown, Hamilton was selected by New York to be a delegate to the Confederation Congress in 1782. As a member of Congress, he was part of a nationalist faction that attempted to use discontent among officers about pay to frighten Congress and the states into adopting an amendment that allowed Congress to tax imports. Certain officers camped at Newburgh, New York, called for force against Congress, and only a personal plea by Washington quelled the so-called Newburgh Conspiracy. Following this incident, Washington warned Hamilton that “the Army is a dangerous instrument to play with.”2

Hamilton served as one of New York’s delegates to the Constitutional Convention at Philadelphia in 1787, and proposed that senators and the executive serve for life, and that the executive have an absolute veto. Although his proposals were not fully adopted, Hamilton passionately campaigned for the Constitution. He joined James Madison and John Jay in writing the Federalist Papers in support of ratification, penning the majority of the essays. Hamilton was also a delegate to the New York ratifying convention in Poughkeepsie during the summer of 1788, and helped convince largely antifederalist New York to ratify the new Constitution.

After George Washington was elected the nation’s first president in 1789, he appointed Hamilton secretary of the treasury. Hamilton sought to create a stable financial foundation for the nation and increase the power of the central government. He pushed for the national government to assume state debts, which would bind creditors to the federal government. Secretary of State Thomas Jefferson and Representative James Madison opposed this plan, and only assisted its passage through Congress when Hamilton agreed to a permanent location for the nation’s capital along the Potomac River. Hamilton made the First Bank of the United States a centerpiece of his financial plan. Modeled on the Bank of England, the bank held government funds, issued loans to the government, provided currency, and increased liquid capital to facilitate economic growth. Hamilton’s opponents, led by Jefferson and Madison, believed his policies dangerously empowered the central government and favored the rich over yeoman farmers. In time, Hamilton and Jefferson became the leaders of the Federalist and Democratic-Republican parties respectively. Jefferson and Hamilton also disagreed over foreign policy. After war broke out between Great Britain and France in 1793, Hamilton favored Washington’s Proclamation of Neutrality, which Jefferson opposed. Jefferson resigned in December 1793, frustrated that Washington usually sided with Hamilton. In 1794, Hamilton helped quell the Whiskey Rebellion, and resigned from his cabinet post in January 1795.

Alexander Hamilton, by James Earle Fraser, ca. 1922. Courtesy Wikimedia Commons.

Hamilton remained active politically after leaving the cabinet, and helped draft Washington’s Farewell Address in 1796. Washington was called out of retirement in 1798 to lead a Provisional Army, when war with France loomed. The aging Washington insisted that Hamilton be his second in command, noting that “I know not where a more competent choice could be made.”3 With Washington’s death in December 1799, Hamilton was briefly the senior-ranking officer of the army, until his departure from the service the following year.

When Thomas Jefferson finished in an electoral tie with Aaron Burr in the election of 1800, some Federalist Congressmen wanted to give Burr the election. Hamilton believed Jefferson was preferable to Burr, and wrote to Federalists imploring them to support Jefferson. In one letter, he said Burr was “a man of extreme and irregular ambition; that he is selfish to a degree which excludes all social affections” and added “he [Burr] is inferior in real ability to Jefferson.”4 Hamilton helped break the congressional deadlock and Jefferson was elected. During the New York gubernatorial election of 1804, the Albany Register published a letter stating that Hamilton had insulted Aaron Burr, one of the candidates, at a private dinner. Burr lost the election, and after confronting Hamilton about the reported slander, challenged him to a duel. On July 11, 1804, Burr mortally wounded Hamilton in Weehawken, New Jersey, and Hamilton died the following day. Eliza survived her husband by fifty years, passing away in 1854.

Today, Hamilton is recognized for his role in creating America’s financial system, and his portrait is on the ten-dollar bill. He gained new acclaim in 2015 with the Broadway production Hamilton, a Tony Award-winning musical about his inspiring rise to prominence.

No comments:

Post a Comment