- In Arizona, more advantaged communities are securing a highly disproportionate share of the funds from the state’s Empowerment Scholarship Account program...Some of the takeaways from this analysis are clear. In Arizona, the state with the first and highest-profile “universal” ESA program, families in the wealthiest, most advantaged communities are obtaining ESA funds at the highest rates. Families in the poorest communities are the least likely to obtain ESA funds. Nothing in the analysis above even remotely suggests that this program is addressing inequities in school access by students’ socioeconomic status.

What is less clear—and worthy of further study—is why these patterns exist.

Here, we’ll examine who is getting public funds through Arizona’s Empowerment Scholarship Account, the oldest universal ESA program in the United States. We focus on whether the primary beneficiaries of these programs are families in need—a key question for judging whether universal ESA programs really are addressing inequities in school access.

The evolution of ESAs in Arizona

Arizona was an early adopter of both an education savings account program and, ultimately, a universal education savings account program. In 2011, Arizona launched the Empowerment Scholarship Account program, which allowed qualifying families to obtain the equivalent of 90% of per-pupil funding in an ESA. (Today, most scholarships provide $7,000 to $8,000 annually.) Initially, the program was restricted to students with disabilities and, through legislative action in 2013, capped at a small number of recipients. Over time, eligibility expanded slightly until, in 2022, Arizona lawmakers opened the program to all students, including those already attending private schools. EdChoice touts the current iteration of the program as the “first to offer full universal funded eligibility with broad-use flexibility for parents.”

The point about broad-use flexibility is important. The list of allowable expenses for Arizona’s ESA program is long. It includes everything from tuition and fees to backpacks, printers, and bookshelves. Overall, about 63% of state funds are being spent on tuition, textbooks, and fees at a qualifying school, with “curricula and supplementary materials” (12%) being the next largest expense.

Researchers, state officials, and advocacy groups have raised concerns about the program’s expansion. Some have pointed to wasteful spending from the lightly regulated program, while others have emphasized exploding costs and their potential impacts on public schools. An early report indicated that a disproportionate share of program beneficiaries appeared to be affluent.

A closer look at who is getting ESA funds in Arizona

We looked to publicly available data on Empowerment Scholarship Account recipients to get a clearer picture of who is receiving ESA funds. If, in fact, affluent families are securing the lion’s share of ESA funding, that would raise obvious questions about whether these programs are exacerbating rather than mitigating inequities in school access.

To begin, we took the most recent executive and legislative quarterly report for the program (the 2024 Q2 report). That report lists the number of students enrolled in the program by the recipients’ home ZIP code. We converted those ZIP codes to ZIP Code Tabulation Areas (ZCTAs), which allows us to describe the communities where ESA enrollees reside using U.S. Census Bureau data.1

In the analyses that follow, we compare ESA participation rates by the socioeconomic status (SES) of Arizona communities. We use three measures of SES: poverty rates, median household income, and educational attainment. This allows us to see, for example, whether wealthier or poorer neighborhoods (ZCTAs) tend to receive a disproportionate share of scholarships.

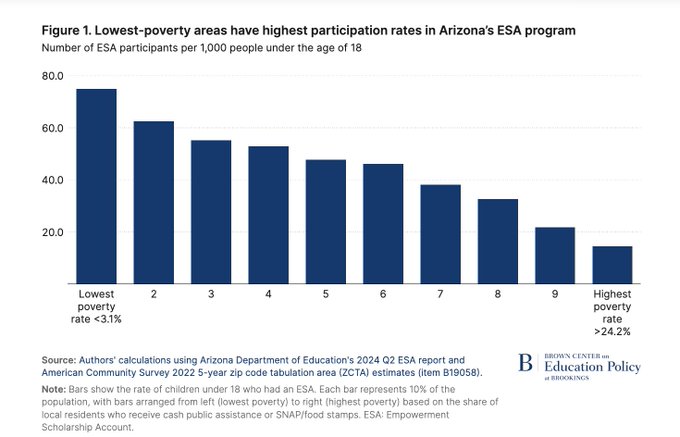

First, we examine ESA participation based on a measure of local poverty: the share of residents receiving public assistance income or SNAP/Food Stamps. For this chart (and others that follow), we divide the Arizona population into deciles, with each bar representing roughly 10% of the state population under the age of 18. In Figure 1, each bar shows the number of ESA recipients per 1,000 people under 18 years old. The leftmost bar represents the parts of the state with the lowest poverty rate (based on ZCTAs); the rightmost bar represents the decile with the highest poverty rate.

We see a clear trend on this measure. As poverty rates increase from left to right, the share of children receiving ESA funding decreases. The highest ESA participation rate—75 ESA recipients per 1,000 children under 18—is for the population decile with the lowest poverty rate. The lowest ESA participation rate—14 ESA recipients per 1,000 children—is for the population decile with the highest poverty rate. (Statewide, we find an average of 45 ESA recipients per 1,000 children.)

Next, we run a parallel analysis based on median household income. This allows us to examine the highest-income areas in ways that a chart based on poverty rates might obscure.

Here, too, the results are clear. As seen in Figure 2, the lowest decile in median income has the lowest rate of ESA participation (20 recipients per 1,000 children), while the highest decile in median income has the highest rate of ESA participation (74 participants per 1,000 children).

When we disaggregate by educational attainment, we see a similar story. Figure 3 shows rates of ESA participation disaggregated by the share of local residents who attended at least some college. ESA receipt is lowest where the fewest people have attended college (14 recipients per 1,000 children). It is highest where the most people have attended college (76 recipients per 1,000 children).

In other words, regardless of the SES measure used (poverty rate, median income, or educational attainment), we see similar patterns in who is obtaining ESA funding. More advantaged communities are securing a highly disproportionate share of these scholarships.

Perhaps these results are driven by varying ESA participation rates across different types of geographic areas? Maybe, for example, ESA uptake is low in rural areas with low population density and fewer nearby private schools. If these areas have relatively low income and college attainment, that could explain the patterns above.

We do, in fact, see higher rates of ESA participation in suburbs (52 per 1,000) and urban areas (45 per 1,000) than in small towns (35 per 1,000) and rural areas (35 per 1,000).2 However, that isn’t the full story.

Let’s take a closer look at the Phoenix metropolitan area. By focusing on one urban/suburban region, we can see whether ESA participation gaps by household income persist even where families have a similar set of schools close to home.

Figure 4a maps ESA participation rates by ZCTA in the Phoenix area, with darker colors indicating higher rates of participation. Figure 4b maps median household income by ZCTA in the Phoenix area, with darker colors indicating higher median household income.

The maps look remarkably similar to one another. Even within this relatively tight geographic area, it’s the wealthiest areas that are home to a lion’s share of ESA recipients.

Learning from Arizona as more states turn to universal ESAs

Some of the takeaways from this analysis are clear. In Arizona, the state with the first and highest-profile “universal” ESA program, families in the wealthiest, most advantaged communities are obtaining ESA funds at the highest rates. Families in the poorest communities are the least likely to obtain ESA funds. Nothing in the analysis above even remotely suggests that this program is addressing inequities in school access by students’ socioeconomic status.

What is less clear—and worthy of further study—is why these patterns exist. There are many reasons why families in lower-SES areas might not participate in this program. Some families might be interested in obtaining ESA funding but are unaware of the program (information barriers) or unable to get to/from their preferred schools (transportation barriers). Some families may confront financial barriers, since the tuition at many private schools exceeds the value of the scholarship, leaving ESA-recipient families to cover the difference. Some families might just not be interested. They may feel better served by, or more welcome in, their neighborhood public schools.

Regardless, if states that have adopted (or are considering) universal ESA programs are serious about using private school choice to address inequities in school access, they need to take a hard look at these programs. The data emerging from Arizona provide plenty of reasons for concern.

Arizona’s ‘universal’ education savi

ngs account program has become a handout to the wealthy