Amna Nawaz:

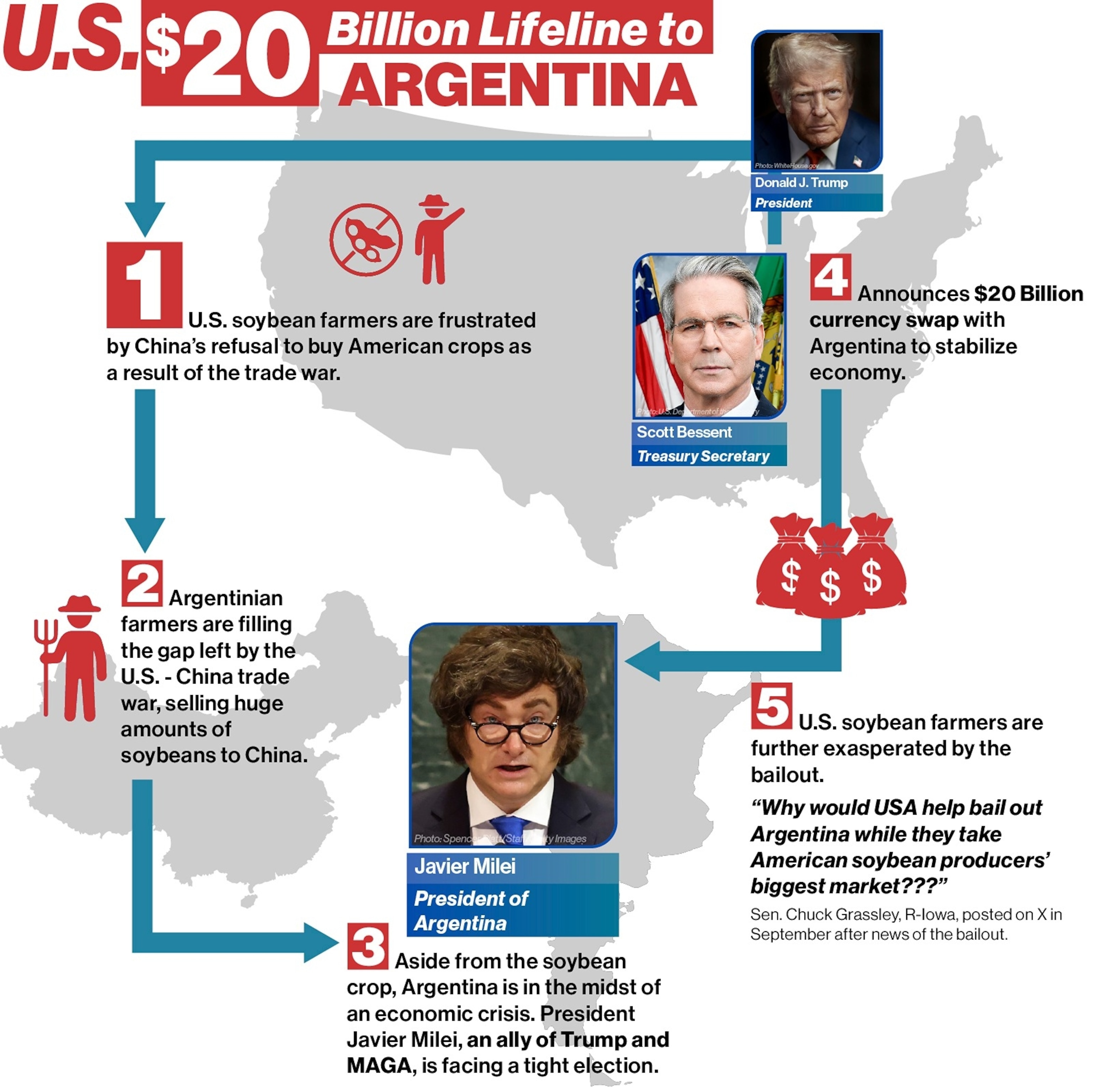

This week, the Trump administration authorized a $20

billion financial lifeline for Argentina as it faces a deepening

economic crisis. But the justification of the deal has raised major

questions and criticism about its merits.

John Yang helps to break it down.

John Yang:

Amna, the United States is exchanging dollars for

Argentine pesos to prop up that currency, which has been losing value

recently. President Trump announced the move on Tuesday as he met with

Argentine President Javier Milei at the White House.

And he made clear that this is contingent on Milei's party winning legislative elections later this month.

Donald

Trump, President of the United States: I'm with this man because his

philosophy is correct. And he may win or he may not win, but I think

he's going to win. And if he wins, we're staying with him, and if he

doesn't win, we're gone.

John Yang:

In addition, Treasury Secretary Scott Bessent has said

the administration is trying to secure an additional $20 billion for

Argentina through private banks and sovereign wealth funds.

Monica de Bolle is an economist at the Peterson Institute for International Economics.

Monica, first of all, what's going on in Argentina that makes this necessary or they're trying to react to?

Monica de Bolle, Peterson Institute for International Economics:

So Argentina is facing the kind of problem that it

usually faces. It's an economy that functions with both the peso and the

dollar. So Argentina is a partially dollarized economy. It uses the

dollar like — as if it were its own currency.

And oftentimes what

happens is that they run into a shortage of dollars. So whenever they

run out of dollars, they fall into crisis, which is what's happening

now, and the U.S. is stepping in to provide the dollars that Argentina

needs.

John Yang:

But, as you say, this happens periodically. This isn't going to fix it, is it?

Monica de Bolle:

No, it's not going to fix it because the underlying

problem that Argentina has is precisely the fact that it uses two

currencies, rather than one. So they have their own currency, but they

also use the dollar.

And that's what always trips them up. So

whenever there is a shock of confidence in the system, whether because

of some domestic problem that popped up or because of an external or

international problem, they run out of dollars, they fall into trouble,

and then somebody has to step in to rescue them.

That somebody has

usually been the International Monetary Fund. But as we have seen in

the past few weeks, now we have the United States stepping in as well.

John Yang:

Is there a danger here of this crisis spreading through

the region that the administration is trying to stop, or what's at risk

here?

Monica de Bolle:

So that's a very good question, because the answer is no.

Argentina

is not a country that poses any risks to either its neighbors, its

surrounding — the surrounding countries, or to the United States, or to

the global economy. Argentina is not a systemic country in that sense.

So,

in the past, when the U.S. has acted in sort of similar ways to what

it's doing in Argentina right now, it has done so because the country in

question was systemic. In other words, it had the potential of having

negative — the crisis in the country had the potential of having

negative consequences on others.

But this is not the case with

Argentina right now. So there is no real economic rationale for the

United States to be stepping in and doing this at this juncture.

John Yang:

No economic rationale. The president said this is

contingent on President Milei's party winning the legislative elections

later this year. What is the president trying to advance? What interest

is he trying to advance by doing this?

Monica de Bolle:

- He's trying to advance two interests. So, on the one

hand, he's trying to prop up what he sees as a political ally. So Milei

is very much perceived as a political ally of the administration. So

there's an interest in keeping him in power and keeping him in office.

He still has two years to go as president of Argentina.

- And the

other — the other driving motive here is geopolitical, because China is

very much involved in Argentina. It is actually very much involved in

the region as a whole. Argentina has a lot of lithium reserves. It also

has a lot of rare earth reserves. So there is an interest, the

geopolitical interest on the part of the U.S., in sort of confronting

China, so to speak, in the region.

So I see this move by the administration as being completely geopolitical and political in nature, not economic at all.

John Yang:

You mentioned China. A lot of soybean farmers in the

Midwest are angry because China stopped buying their product because of

the trade war and are buying — is buying soybeans from Argentina. They

see them that this is a lifeline being thrown to a competitor. What do

you say to that?

Monica de Bolle:

Yes, it is problematic because that is happening. China

has stopped buying soybeans from the United States. It's buying soy from

Argentina and from Brazil, which Brazil is the largest producer in the

region. But Argentina also produces a lot of grains and a lot of

soybeans.

And China has just stepped up its purchases of these

products from both countries, but notably in our case here Argentina.

So, yes, U.S. farmers have very much a right to be angry at this

situation.

John Yang:

You say there's no economic reason why the government has

to do this, the United States has to do this. Is there a risk to the

United States by doing this?

Monica de Bolle:

There surely is, because this is the situation that the

U.S. is walking into without any endgame in sight. So, in other words,

the U.S. is stepping in to provide a lifeline for Argentina, but it

doesn't really know how this ends.

And, with Argentina, the story

usually goes like this. You lend to them. They usually don't pay back.

So you face a situation — this is what's been going on with the IMF for

the past 20-something years. And so what happens is you either have to

keep lending to Argentina in order to keep them afloat and in order for

you to repay yourself, or you stop lending to Argentina, in which case

you throw them into crisis.

So with the U.S., it's kind of a

no-win situation here, because the moment the U.S. steps in to provide

Argentina with this lifeline, it either has to commit to staying in

Argentina and keep providing Argentina lifelines if it faces further

problems down the road, or the U.S. at some point will have to step

back.

And when they do, Argentina will fall into a crisis and guess who will be blamed? The U.S.

John Yang:

Monica de Bolle of the Peterson Institute for International Economics, thank you very much.

Monica de Bolle:

Thank you.