Good timing huh. . . For now, most chip supply chain experts predict a relatively shallow downturn, provided that the global economy is heading for a soft landing. But the speed with which things have turned has left them scrambling to understand the complex dynamics at work.Will Intel emerge as a “national champion” in a technological cold war with China? Probably not, since fabs are dispersed around the world. Hence, it’s unlikely Intel becomes America’s answer to TSMC.

US chipmakers hit by sudden downturn after pandemic boom

s gaming chips fell 44 percent from the preceding quarter. And Micron, one of the largest makers of memory chips, said its free cash flow was likely to turn negative in the next three months, after averaging $1 billion in recent quarters.

The stresses have also been felt throughout Asia. Late last week, the chief executive of Chinese chipmaker Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation said demand had slowed from smartphone and other consumer electronics makers, with some stopping orders altogether. A month before, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company said it was expecting an inventory correction that would last until late next year.

The abrupt slide has left chipmakers in the US trying to manage a decline at the very moment that they were laying the ground for a huge increase in production because of the $52 billion in government support provided by this month’s Chips Act.

On the same day that Congress passed the law, Intel, which is expected to be the biggest beneficiary of government grants, sliced $4 billion from its capital spending plans for the rest of this year, although it said that it was still committed to a “strong and growing dividend” for its shareholders.

Meanwhile, Micron, which celebrated President Joe Biden’s signing of the legislation last week with the announcement that it planned to invest $40 billion in the US by the end of the decade, was forced just a day later to say it would cut its capital spending “meaningfully” next year because of the downturn.

For now, most chip supply chain experts predict a relatively shallow downturn, provided that the global economy is heading for a soft landing. But the speed with which things have turned has left them scrambling to understand the complex dynamics at work.

Gartner, which had been expecting the growth in global chip sales this year to halve from 2021’s 26 percent, took its forecast down further to 7 percent and is now predicting a 2.5 percent contraction in 2023 to $623 billion.

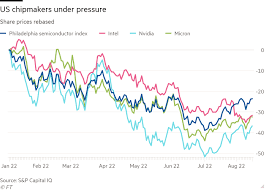

For now, Wall Street has taken the news in its stride. The Philadelphia semiconductor index, which comprises the 30 largest US companies involved in the design, manufacture, and sale of semiconductors, fell back almost 40 percent as the stock market corrected this year after rising three-fold following the early pandemic stock market slump. But since early July, despite mounting evidence of the chip slowdown, the index has rebounded 24 percent.

On Monday, Nvidia’s shares climbed back above the level they were trading at before its earnings disappointment, even though it disclosed a savage 17 percent shortfall in revenue compared with earlier expectations.

But after the severe inventory and supply chain stresses of the past two years, few analysts are confident that they can judge how an economic slowdown will feed through the industry. Hopes that the slide would be largely restricted to the PC and smartphone markets have already been dashed.

While a collapse in demand in the gaming market was the main cause for Nvidia’s earnings disappointment, the US chipmaker also said its sales of data center chips had only risen 1 percent from the preceding three months, compared with Wall Street expectations of closer to 10 percent. It blamed supply shortages rather than falling demand, although other indications, including a fall-off at Intel, have fed the suspicion that the booming cloud computing market has cooled rapidly.

In recent days, the signs of retrenchment have broadened. Micron finance chief Mark Murphy said last week that industrial and automotive customers were the latest to cut their chip purchases.

“It’s a very recent development,” he added, making it too early to tell whether these customers are simply making an adjustment after a rapid inventory build-up, or whether they are responding to falling demand from their own customers.

Either way, according to Murphy, the result has been the same: “We’re seeing clear signs of weakness in those markets.”

s gaming chips fell 44 percent from the preceding quarter. And Micron, one of the largest makers of memory chips, said its free cash flow was likely to turn negative in the next three months, after averaging $1 billion in recent quarters.

The stresses have also been felt throughout Asia. Late last week, the chief executive of Chinese chipmaker Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corporation said demand had slowed from smartphone and other consumer electronics makers, with some stopping orders altogether. A month before, Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company said it was expecting an inventory correction that would last until late next year.

The abrupt slide has left chipmakers in the US trying to manage a decline at the very moment that they were laying the ground for a huge increase in production because of the $52 billion in government support provided by this month’s Chips Act.

On the same day that Congress passed the law, Intel, which is expected to be the biggest beneficiary of government grants, sliced $4 billion from its capital spending plans for the rest of this year, although it said that it was still committed to a “strong and growing dividend” for its shareholders.

Meanwhile, Micron, which celebrated President Joe Biden’s signing of the legislation last week with the announcement that it planned to invest $40 billion in the US by the end of the decade, was forced just a day later to say it would cut its capital spending “meaningfully” next year because of the downturn.

For now, most chip supply chain experts predict a relatively shallow downturn, provided that the global economy is heading for a soft landing. But the speed with which things have turned has left them scrambling to understand the complex dynamics at work.

Gartner, which had been expecting the growth in global chip sales this year to halve from 2021’s 26 percent, took its forecast down further to 7 percent and is now predicting a 2.5 percent contraction in 2023 to $623 billion.

For now, Wall Street has taken the news in its stride. The Philadelphia semiconductor index, which comprises the 30 largest US companies involved in the design, manufacture, and sale of semiconductors, fell back almost 40 percent as the stock market corrected this year after rising three-fold following the early pandemic stock market slump. But since early July, despite mounting evidence of the chip slowdown, the index has rebounded 24 percent.

On Monday, Nvidia’s shares climbed back above the level they were trading at before its earnings disappointment, even though it disclosed a savage 17 percent shortfall in revenue compared with earlier expectations.

But after the severe inventory and supply chain stresses of the past two years, few analysts are confident that they can judge how an economic slowdown will feed through the industry. Hopes that the slide would be largely restricted to the PC and smartphone markets have already been dashed.

While a collapse in demand in the gaming market was the main cause for Nvidia’s earnings disappointment, the US chipmaker also said its sales of data center chips had only risen 1 percent from the preceding three months, compared with Wall Street expectations of closer to 10 percent. It blamed supply shortages rather than falling demand, although other indications, including a fall-off at Intel, have fed the suspicion that the booming cloud computing market has cooled rapidly.

In recent days, the signs of retrenchment have broadened. Micron finance chief Mark Murphy said last week that industrial and automotive customers were the latest to cut their chip purchases.

“It’s a very recent development,” he added, making it too early to tell whether these customers are simply making an adjustment after a rapid inventory build-up, or whether they are responding to falling demand from their own customers.

Either way, according to Murphy, the result has been the same: “We’re seeing clear signs of weakness in those markets.”

✓

U.S. CHIPS Act Takes Center Stage in Post-Globalized Industry - EE Times Asia

To manufacture highly integrated circuits in the United States is no longer just a nice-if-we-can idea. It is building momentum.

The U.S. economy is tanking, America is recording more than 1,000 coronavirus deaths daily, millions file for unemployment benefits each week. Amid the crises, chips are taking center stage in what looks like a new, pandemic-driven industrial policy .

Manufacturing advanced and secure circuits domestically is no longer just a talking point. Momentum is building, observers note.

The Creating Helpful Incentives for Producing Semiconductors in America Act is wending its way through the congressional budget process. Politicians, bureaucrats and semiconductor companies – including Intel – increasingly back efforts to beef up chip production on US soil.

With “real money” likely available by the fall, the domestic chip industry industry is scurrying for a piece of the action.

A key question remains: Whether the bill offers substantive funds, or is just “another paper tiger”? says Dan Hutcheson, CEO of VLSI Research. More important, will the U.S. government stick to this new industrial policy for the long term?

With Congress in its August recess, EE Times offers the primer – who, what and how of the CHIPS Act. We also examine why both the US government and semiconductor industry are in the midst of a 180-degree reversal of the globalization drumbeat they have followed for decades.

We spoke with James Lewis of the Center for Strategic and International Studies and VLSI Research’s CEO Hutcheson.

What’s in the CHIPS For America Act?

Section 1091: Incentive grants not to exceed $3

billion for any chip manufacturing project. Grants would be dispersed by

the Commerce Department for projects focused on chip assembly, testing,

packaging, fabrication and R&D.

Section 1092: Defense Department industrial partnerships to advanced secure microelectronics for use by the U.S. government and to build secure supply chains. The provision requires DoD planners to report progress to Congress on both fronts.

Section 1093: Requires a Commerce Department study on the status of microelectronics technology and the defense industrial base. A relatively short timeframe of 120 days is specified to submit the status report.

Section 1094: Funding to develop “measurably” secure microelectronics, including a multilateral secure microelectronics fund to allow the U.S. to work with allies and partners to forge a standard approach to secure microelectronics.

Section 1095: Funds advanced semiconductor R&D overseen by the National Science and Technology Council. Also directs the Secretary of Commerce to work with the Manufacturing Institute to conduct research and promote workforce training.

“The only caveat is the companies that use this money have to make sure the intellectual property remains controlled by the U.S.,” said James Lewis of the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). “We’ll see what survives [the House-Senate] conference, but I think most of these will make it through.”

Will Intel emerge as a “national champion” in a technological cold war with China? Probably not, since fabs are dispersed around the world. Hence, it’s unlikely Intel becomes America’s answer to TSMC.

Others wait in the wings, including GlobalFoundries and agile U.S.-owned partner SkyWater. Those capabilities offer the possibility of ramping up chip manufacturing skills in areas like packaging, test and assembly. After four decades of outsourcing, those capabilities are seen as the best way for western chip makers to move up the production learning curve.

Ultimately, those manufacturing skills could prove as strategic as 7nm, 5nm and finer chip geometries. “The focus here is not on making any one American company the champion,” Lewis of CSIS says, “but in making sure TSMC isn’t selling to a potential enemy.”

Meanwhile, Beijing is investing heavily in Shanghai-based SMIC, Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corp., as its national champion. SMIC represents Beijing’s hedge should it be cut off from access to TSMC’s leading-edge manufacturing technology. Lewis suggests the U.S. strategy includes a combination of huge investments, export controls and other sanctions to maintain and extend western chip dominance.

Will Intel go for becoming a ‘trusted fab’?

Just like Lewis, Hutcheson agrees that Intel will not likely

try to become the next TSMC. The custom foundry business requires a very

different culture and manufacturing base to serve its customers.

However, he pointed out that Intel could carve off some of its fab capacity for making defense products. Intel today, however, is not designated as a “trusted fab” by the DoD.

While defense doesn’t require a lot of capacity, it would be a mistake to think any smallish fab could do the job. Contrary to the conventional wisdom, Hutcheson said that defense customers demand that fabs have “on-going volume manufacturing” capability to make products at the extreme edge.

Defense-qualified fabs “need to roll a lot of wafers to actually get high-quality parts,” said Hutcheson, “like stuff used in things like iPhones.”

Consider the VHSIC (Very High-Speed Integrated Circuits) launched by the US Department of Defense in 1980. This government program met challenges, and hard lessons were learned, according to Hutcheson.

The VHSIC’s goal was to lead advances in IC materials, lithography, packaging, testing and algorithms. Initially, this was planned as a small-scale fab to advance defense manufacturing, budgeted with $20 million. Hutcheson said, “I kept pointing out then, no, you need billions of dollars, not millions.” The VHSIC program ended up spending more than $1 billion for silicon integrated circuit technology development.

Today, the good news is the availability of leading fabs in the United States, including GlobalFoundries and SkyWater. TSMC (if it keeps a promise to come to Arizona) and Intel, once designated as a trusted fab, could join the parade.

What lit the fire under Congress?

Beijing laid down the gauntlet with its aspirational technology roadmap, Made in China 2025,

that seeks to move slowly by steadily up the semiconductor food chain

over the next half decade. Dominating the global chip industry is among

several high-tech goals, and China is pouring billions into its chip

strategy. Whether it can deliver remains to be seen. Either way, U.S.

policy makers are looking over their shoulders, waiting to see if

Chinese chip makers can duplicate early successes in AI and aerospace.

One thing is certain: Beijing is committing billions to silicon R&D, underscoring the strategic importance of electronics in a technology cold war centered on semiconductors. “There’s a sense that the American leadership is threatened by these huge Chinese investments accompanied by predatory pricing and espionage and the usual bag of tricks,” according to Lewis...

Is manufacturing coming back?

No, the US won’t be assembling iPhones in America.

But for high-end manufacturing such as semiconductors, it’s “quite possible,” Hutcheson noted.

Accelerating such a move are rising geopolitical concerns. Think military threats by China, highlighted by its claims in and around the South China Sea.

During the last century, the US government kept the machine tool industry alive as a hedge for weapons manufacturing. The same principle might well apply to the semiconductor industry, the backbone of modern society and technology warfare.

✓ RELATED

.jpg)

.png)

.png)

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment