- Current and planned Russian offensives will very likely culminate without achieving operationally decisive gains and in ways that could very well create propitious conditions for Ukrainian counter-offensives, especially once Ukraine has ingested the incoming Western tanks. ..

- Ukraine may still launch a long-planned counteroffensive this winter, which would somewhat mitigate the consequences of Western delays in providing necessary aid. The delay in launching that counter-offensive thus far, however, has allowed the Russians to set conditions to make it harder and more costly.

- The delay has also allowed Russia to set conditions for an offensive of its own, greatly complicating Ukrainian campaign design.

>

RUSSIAN OFFENSIVE CAMPAIGN ASSESSMENT, JANUARY 29, 2023

Frederick W. Kagan, Kimberly Kagan, Riley Bailey, Grace Mappes, Angela Howard, Mason Clark, Kateryna Stepanenko, and George Barros

January 29, 8:30 pm ET

Click here to see ISW’s interactive map of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. This map is updated daily alongside the static maps present in this report.

ISW is publishing an abbreviated campaign update today, January 29. This report focuses on the impact of delays in sending high-end weapons systems to Ukraine on Ukraine’s ability to take advantage of windows of opportunity throughout this war.

- Western discussions of supposed “stalemate” conditions and the difficulty or impossibility of Ukraine regaining significant portions of the territory Russia seized in 2022 insufficiently account for how Western delays in providing necessary military equipment have exacerbated those problems.

- Slow authorization and arrival of aid have not been the only factors limiting Ukraine’s ability to launch continued large-scale counter-offensive operations.

- Factors endogenous to the Ukrainian military and Ukrainian political decision-making have also contributed to delaying counteroffensives.

- ISW is not prepared to assess that all Ukrainian military decisions have been optimal. (ISW does not, in fact, assess Ukrainian military decision-making in these updates at all.

- But Ukraine does not have a significant domestic military industry to turn to in the absence of Western support.

- Western hesitancy to supply weapons during wartime took insufficient account of the predictable requirement to shift Ukraine from Soviet to Western systems as soon as the West committed to helping Ukraine fight off Russia's 2022 invasion.

The military aid provided by the US-led Western coalition has been essential to Ukraine’s survival, and this report’s critiques illustrate the importance of that aid as well as its limitations. Western military advising before the February 24 invasion helped the Ukrainian military resist the initial Russian invasion. Western weapons systems such as the Javelin anti-tank missile helped Ukraine defeat that onslaught and throw the Russian drive on Kyiv back to its starting points.

- The provision of essential Soviet-era weapons systems and munitions by members of the Western coalition has kept the Ukrainian military operating throughout the war.

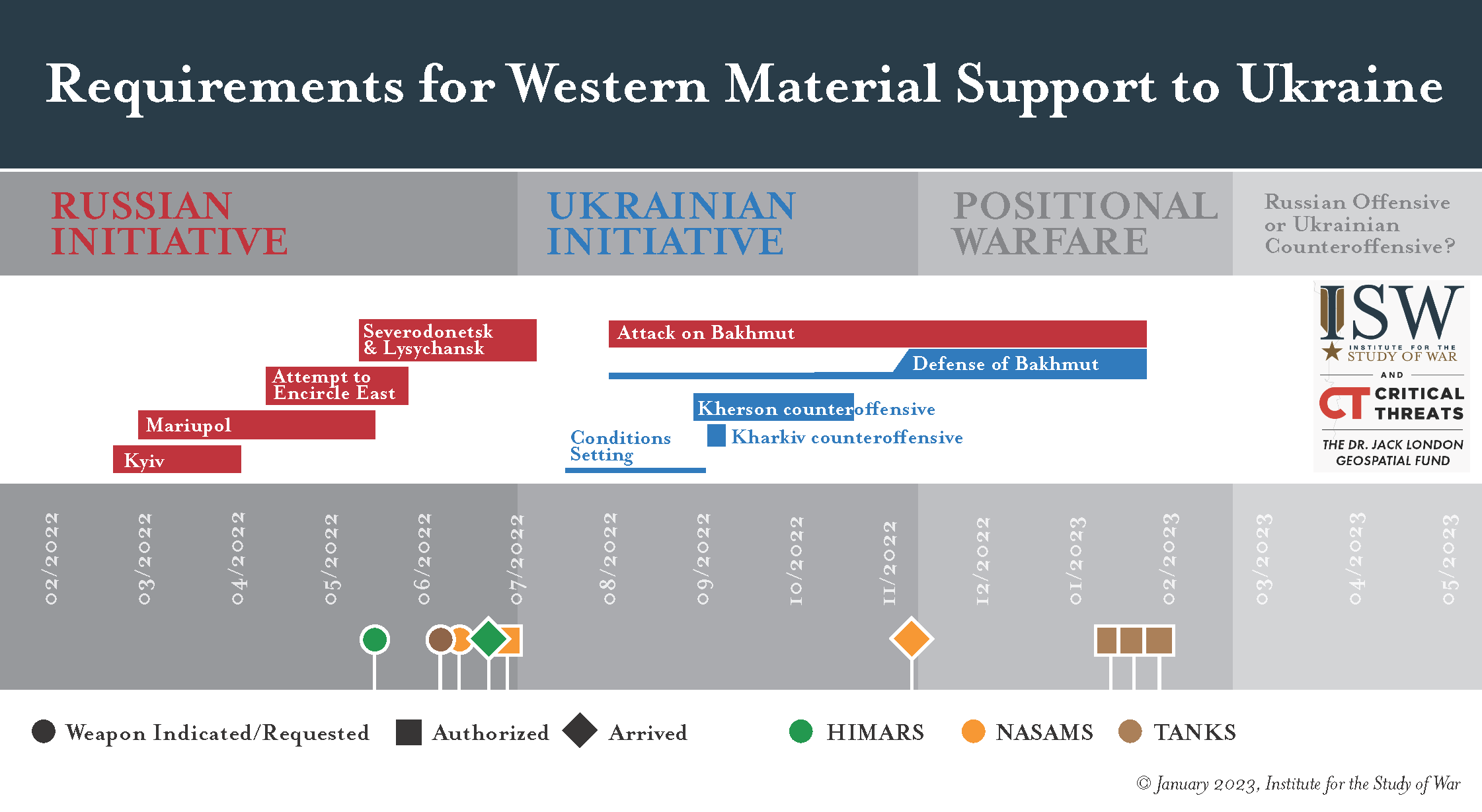

- The delivery of more advanced Western systems such as the US-produced 155mm artillery (in April) and then HIMARS (in June) facilitated the Ukrainian counter-offensives that liberated most of Kharkiv Oblast and then western Kherson Oblast.[1] The arrival of Western NASAMS air-defense systems in November helped blunt the Russian drone and missile campaign attacking Ukrainian civilian infrastructure.[2]

The war has unfolded so far in three major periods.

- The Russians had the initiative and were on the offensive from February 24 through July 3, 2022, whereupon their attacks culminated. The Ukrainians seized the initiative and began large-scale counteroffensives in August, continuing through the liberation of western Kherson Oblast on November 11.

- Ukraine has been unable to initiate a new major counter-offensive since then, allowing the conflict to settle into positional warfare and allowing the Russians the opportunity to regain the initiative if they choose and to raise the bar for future Ukrainian counteroffensives even if they do not.

- The pattern of delivery of Western aid has powerfully shaped the pattern of this conflict.

Western reluctance to begin supplying Ukraine with higher-end Western weapons systems, particularly tanks, long-range strike systems, and air-defense systems, has limited Ukraine’s ability to initiate and continue large-scale counter-offensive operations.

Sound counter-offensive campaign design calls for stopping the enemy’s offensive as rapidly as possible, initiating decisive counter-offensives rapidly after the enemy’s offensive culminates to take advantage of the enemy’s disorganization and unpreparedness for subsequent major operations, and then continuing counter-offensive operations with the briefest possible pauses between them to prevent the enemy from reconstituting its forces and possibly regaining the initiative.

Many factors contribute to the failure of most militaries to meet this ideal standard, and the Ukrainian military faced many internal challenges to do so. Weapons and supplies are always central to the planning and execution of sound campaigns, however. Ukraine had no meaningful defense industry going into the war and was therefore almost entirely reliant on its Western backers to provide the materiel it needed to stop the initial Russian offensive and then, even more so, to initiate and sustain counter-offensives. The patterns of Western aid thus heavily shaped Ukraine’s ability to develop and execute sound campaign plans.

The Russian invasion began on February 24, 2022. The only major phase of Russian offensive operations continued through the capture of Lysychansk on July 3.[3] Russian offensive operations then culminated, and Russia lost the initiative in July.

Indicators that the Russian offensives would culminate and that Western weapons would be needed at scale emerged clearly in late May and June. ISW observed on May 28 that “Ukraine may have a chance to launch significant counteroffensives with good prospects for success.”[4] The West had been sending Ukraine Soviet-era equipment and ammunition to resupply and replace Ukraine’s Soviet systems, but Ukrainian Main Military Intelligence Directorate (GUR) Head Vadym Skibitsky warned on June 10 that Ukrainian forces were running low on Soviet supplies.[5] Western officials began publicly warning that stocks of Soviet-era materiel were running low on June 24.[6] The United States authorized the delivery of 155mm howitzers on April 21, and those systems began arriving in Ukraine on April 29.[7]The United States authorized HIMARS in late May, which began arriving on June 23.[8] The Western coalition did not prepare to provide Ukraine with armored vehicles during this period.[9]

If the West’s aim had been to shorten the war by speeding Ukraine’s liberation of occupied territory, the assessment that stocks of Soviet-era weapons held by friendly states were running low should have triggered a fundamental change in the provision of Western aid starting in June 2022. The Western coalition has no capacity to produce Russian weapons or ammunition at scale, so the exhaustion of the Cold War holdovers of those systems clearly indicated that the West would have to shift Ukraine to full reliance on Western systems in order for Ukraine to have any military at all in the future, to say nothing of supporting Ukraine’s continued ability to fight a protracted war against Russia. The West should therefore have begun setting conditions to shift Ukraine onto the use of Western weapons platforms, including tanks, artillery, and aircraft, by early summer 2022 and in advance of the forecasted culmination of Russian offensive operations.

Ukraine used what systems the West made available to it to take advantage of the window of opportunity presented by the Russian culmination following the seizure of Lysychansk on July 3, 2022, to initiate counter-offensive operations. Ukrainian forces began using US-provided HIMARS systems to set conditions for counter-offensives in both Kharkiv and Kherson oblasts in July. Ukraine launched its first major counter-offensive, in Kharkiv Oblast, on September 6.[10] That counter-offensive was a stunning success, recouping over 12,000 square kilometers of territory in a six-day lightning advance that overran and destroyed some of the most elite mechanized units in the Russian military.[11]

The Ukrainians followed the Kharkiv counter-offensive with a counter-offensive in Kherson Oblast. They began setting conditions for operations in Kherson as early as July 23, escalating in September and October, and culminating in the Russian withdrawal from western Kherson Oblast on November 11, 2022.[12] That counter-offensive proceeded much more slowly and cautiously than the Kharkiv counteroffensive had, partly because the Ukrainians wanted to avoid fighting in (and thereby destroying) the city of Kherson, but largely because by that point they feared running out of counter-offensive capabilities. The West was still refusing to supply armored vehicles and was increasingly warning about Western shortages of supply even of the artillery systems and munitions it was providing.[13]

Had the West begun providing Ukraine the equipment it needed for sustained counter-offensive operations as the Russian offensives were culminating, it might have been possible for Ukraine to begin those counter-offensive operations earlier.[14] If the West had begun working to shift Ukraine fully to Western systems when the need to do so had become apparent in the summer of 2022, conditions could have been set to allow Ukraine to continue counter-offensive operations after Kherson and thereby deprive the Russians of the ability to reconstitute their forces and attempt to regain the initiative.

Western delays in providing Ukraine the materiel needed for counter-offensive operations have instead had a snowballing effect on Ukrainian abilities to conduct and sustain counter-offensives. Having failed to begin setting conditions to send Ukraine armored vehicles in May and June, when the need was becoming apparent, the West still did not prepare to do so when the Ukrainian counter-offensives began. The Ukrainians thus lacked any assurance that they would receive replacements for weapons systems lost or damaged in a new counter-offensive and therefore likely became more cautious in deciding to initiate and continue counter-offensives after liberating western Kherson Oblast.

Failure to commit to providing counter-offensive materiel at scale after the conclusion of the Kherson counter-offensive has contributed to delays in the initiation of any further counter-offensives. The effects of that failure and of the cautiousness it likely induced in Ukrainian leaders may help explain the fact that Ukrainian officials routinely indicated that they intended to continue counteroffensives in the winter of 2022 and 2023 while some Western officials said instead that they anticipated a lull in fighting during the winter and therefore did not see any urgency in providing additional materials.[15] Ukrainian forces, in any event, have not initiated a new large-scale counter-offensive following the Russian withdrawal from west bank Kherson Oblast in mid-November.[16]

The Russians have taken advantage of these delays and failures to benefit from the windows of vulnerability their own defeats and incompetence produced by mobilizing manpower and equipment and starting to rationalize their own forces. They renewed their offensive against Bakhmut in late July, although it picked up steam only when Wagner Forces began leaning into it (although without making significant territorial gains) in October-November.[17] The Bakhmut offensive coincided with the dramatic air campaign against Ukrainian civilian infrastructure that started on October 10 and made use of Russia’s remaining stocks of precision missiles as well as drones that Moscow procured from Iran.[18] Both the Bakhmut offensive and the missile-drone campaign put pressure on Ukraine that distracted from efforts to prepare for further counter-offensives—the Bakhmut offensive by drawing Ukrainian reinforcements to the defense of the city and the infrastructure attacks by diverting Ukrainian command attention from the battlefield. The muddy season in October and November also slowed operations but did not stop them.[19]

The initial deployments of mobilized Russian reservists were largely disastrous for Russia and did not pose a major obstacle to Ukraine’s continuation of counter-offensive operations.[20] As the months went on and stretched into 2023, however, the Russians redeployed conventional units, likely filled out with mobilized reservist replacements, to stiffen the sector of the front (Luhansk) toward which the next Ukrainian counter-offensive appeared to be headed and filled out those units with mobilized personnel in a more effective way.[21] Russian forces also spent considerable resources in the fall of 2022 establishing a long line of supporting field fortifications in Luhansk Oblast to defend against Ukrainian advances.[22] The mass mobilization of Russian convicts by the Wagner Group rapidly generated tens of thousands of “soldiers” who were used in human wave attacks that generated dreadful casualties on the Russian side but placed great pressure on Ukrainian defenders in November, December, and January.[23]

Ukraine’s inability to mount a subsequent counter-offensive in November following the Russian withdrawal from western Kherson Oblast gave Russia time and space to stabilize its lines and put pressure on Ukraine to which Kyiv had to respond.[24] Many factors no doubt contributed to Ukraine’s failure to continue counter-offensive operations after Kherson, but the West’s failure to provide the necessary materiel was certainly key. That failure thus allowed the Russians partially to regain the initiative in the war starting in November and to establish defensive positions posing a much greater challenge for the next counter-offensive than the Russians could have posed in November-December.[25]

The incorporation of Western weapons systems such as tanks and aircraft takes a long time. Many Ukrainian soldiers must be trained to use them. Logistics systems must be established to supply them. Spare parts must be assembled and depots equipped to repair them. The inevitable delay between the pledge to send such systems and the Ukrainians’ ability to use them means that Western leaders must commit them when the earliest indicators that they will be required appear, not when the situation becomes dire. Had Western leaders started setting conditions for Ukraine to use Western tanks in June 2022, when the first clear indicators appeared that Western tanks would be needed, Ukrainian forces would have been able to start using them in November or December.

The continual delays in providing Western materiel when it became apparent that it is or will soon be needed have thus contributed to the protraction of the conflict. They are not the only reason for that protraction, to be sure, but the West must recognize the contributions these delays have made to hindering Ukraine’s ability to liberate more of its territory faster.

Recent Western commitments to provide Ukraine with the tanks and armored vehicles it requires for further counter-offensive operations are important, but the delays in making those commitments may have cost Ukraine a window of opportunity for a counter-offensive this winter. Russian forces are likely preparing to launch an offensive of their own in Luhansk Oblast and are adding weight to their offensives around Bakhmut, as ISW has reported.[26]

Ukraine may still launch a long-planned counteroffensive this winter, which would somewhat mitigate the consequences of Western delays in providing necessary aid. The delay in launching that counter-offensive thus far, however, has allowed the Russians to set conditions to make it harder and more costly. The delay has also allowed Russia to set conditions for an offensive of its own, greatly complicating Ukrainian campaign design.

If Ukraine does not already have the materiel it needs to launch its counteroffensive, then it may have to wait many weeks for Western tanks to arrive in enough quantity to support renewed efforts. The delay will likely be lengthened by the weather. Both the Russians and the Ukrainians will have to account for the spring muddy season, most likely to occur in March and April, that will make high-speed mechanized counter-offensives difficult if not impossible. Ukraine may need to wait until late spring or early summer before renewing its large-scale efforts to liberate strategically vital terrain. Ongoing Russian offensives may well make more gains before then.

The West will need to avoid drawing the erroneous conclusion that future Ukrainian counter-offensives are impossible based on a timeline imposed by the West’s own delays in providing necessary material and meteorological conditions. Current and planned Russian offensives will very likely culminate without achieving operationally decisive gains and in ways that could very well create propitious conditions for Ukrainian counter-offensives, especially once Ukraine has ingested the incoming Western tanks. ISW continues to assess that Ukraine can liberate critical terrain with the current and promised levels of Western support and that it is a matter of vital national interest for the United States and its Western partners that Ukraine do so.

Key inflections in ongoing military operations on January 29:

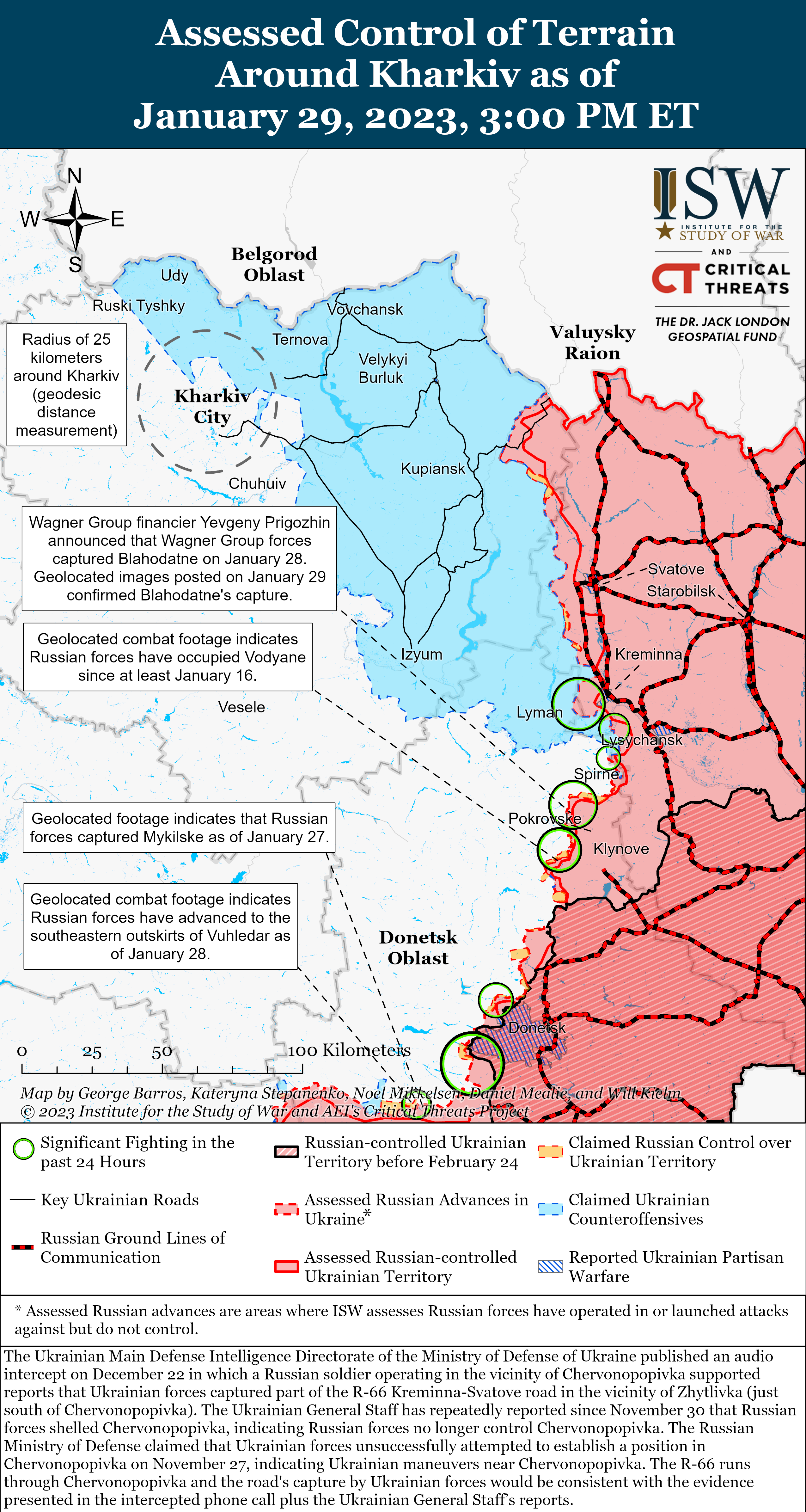

- Russian sources claimed that Ukrainian forces continued counteroffensives in the vicinity of Kuzemivka (about 16km northwest of Svatove).[27]

- Ukrainian officials reported that Ukrainian forces continued to repel limited Russian counterattacks west and south of Kreminna.[28]

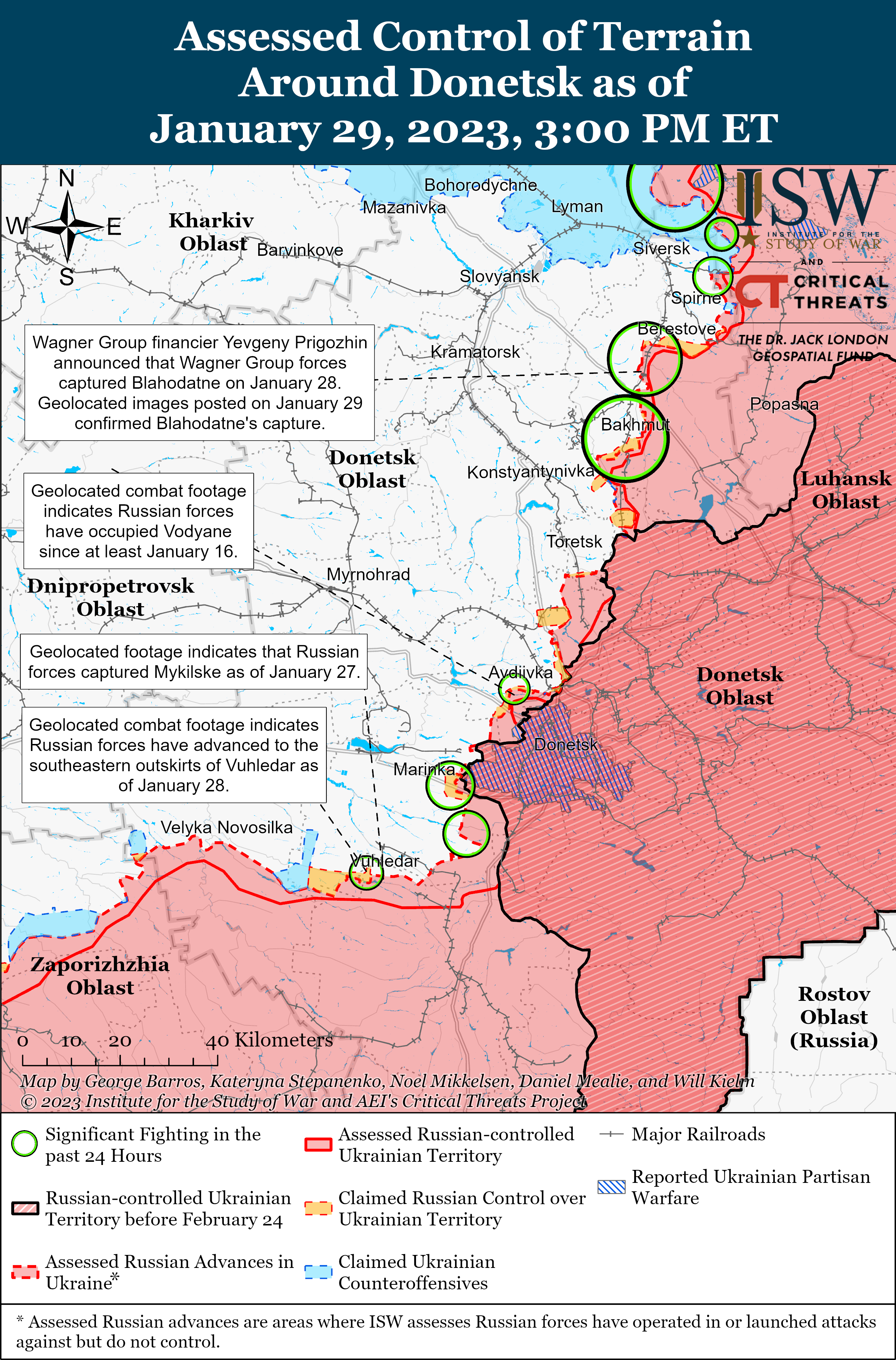

- Wagner Group financier Yevgeny Prigozhin announced that Wagner forces seized Blahodatne (about 12km northeast of Bakhmut) on January 29.[29]

- Russian forces continued to conduct ground attacks in the Bakhmut and Donetsk City-Avdiivka areas.[30]

- Ukrainian officials reported that Ukrainian forces repelled assaults near Pobieda (4km southeast of Donetsk City) and Vuhledar.[31] Russian sources claimed that fighting is ongoing to the west and east of Vuhledar.[32]

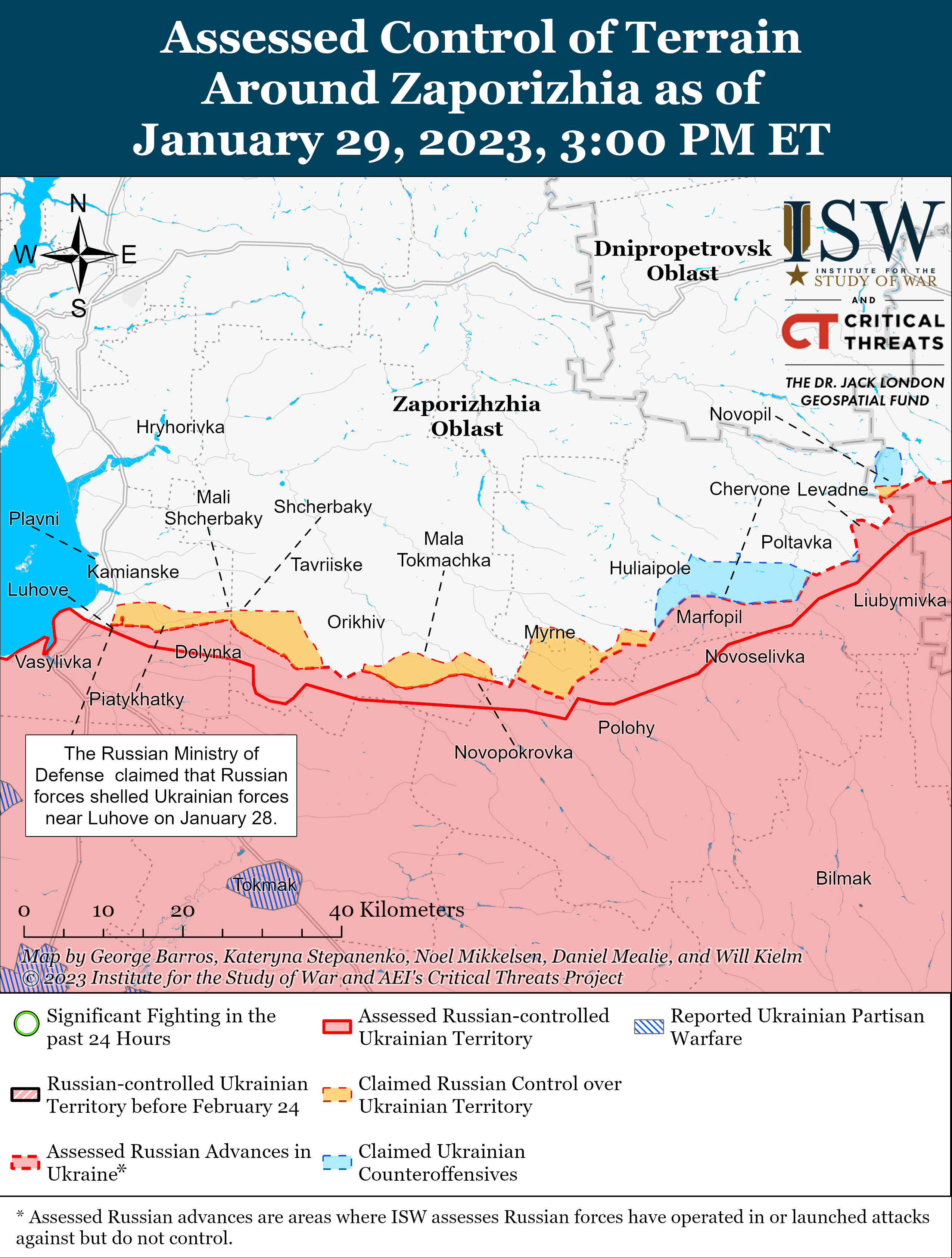

- Russian sources did not report on any Russian ground attacks in Zaporizhia Oblast for the third consecutive day on January 29.[33] Ukrainian forces conducted a HIMARS strike against a bridge in Svitlodolynske (20km northeast of Melitopol).[34]

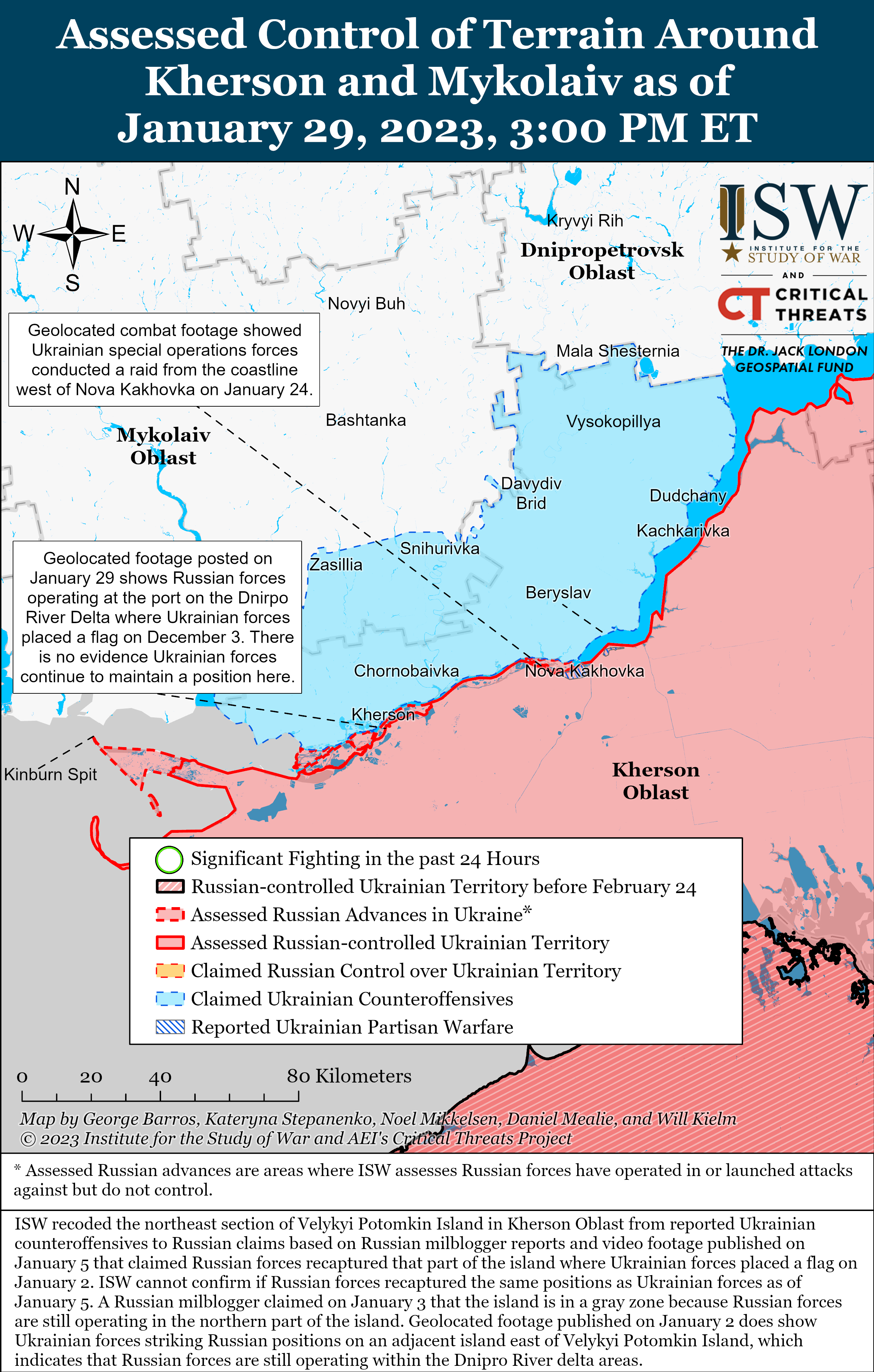

- Russian forces continued to conduct routine fire against Kherson City and other settlements in the west (right) bank of the Dnipro River.[35] Kherson Oblast Administration Advisor Serhiy Khlan reported that Russian forces used incendiary munitions to fire on Beryslav.[36]

- Russian authorities are continuing to set conditions for a second wave of mobilization. Head of the State Duma Committee on Defense Andrey Kartapolov stated on January 28 that the committee is reviewing over 20 laws regarding mobilization deferrals.[37]

- The Ukrainian General Staff reiterated that it has not observed Russian forces in Belarus forming a strike group as of January 29.[38]

Note: ISW does not receive any classified material from any source, uses only publicly available information, and draws extensively on Russian, Ukrainian, and Western reporting and social media as well as commercially available satellite imagery and other geospatial data as the basis for these reports. References to all sources used are provided in the endnotes of each update.

No comments:

Post a Comment