Monday, March 21, 2022

INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY RIGHTS CONCERNS?? Ukrainian Soldier Moves To Trademark ‘Russian Warship, Go Fuck Yourself”

A story from Snake Island that Timothy Geigner in a report from Techdirt didn't see coming

Ukrainian Soldier Moves To Trademark ‘Russian Warship, Go Fuck Yourself”

Because Of Course

from the licensing-bravery dept

Fri, Mar 18th 2022 03:45pm - Timothy Geigner

from the licensing-bravery dept

"Thanks to Vladimir Putin and his one-man show designed to educate the world on just what can happen when a murderous dictator decides to throw a fit, the news is chock full of Ukraine. This has included Techdirt’s pages, which really shouldn’t be that big of a surprise. Still, I will admit that I didn’t see the possibility of trademark-related stories coming out of the war.

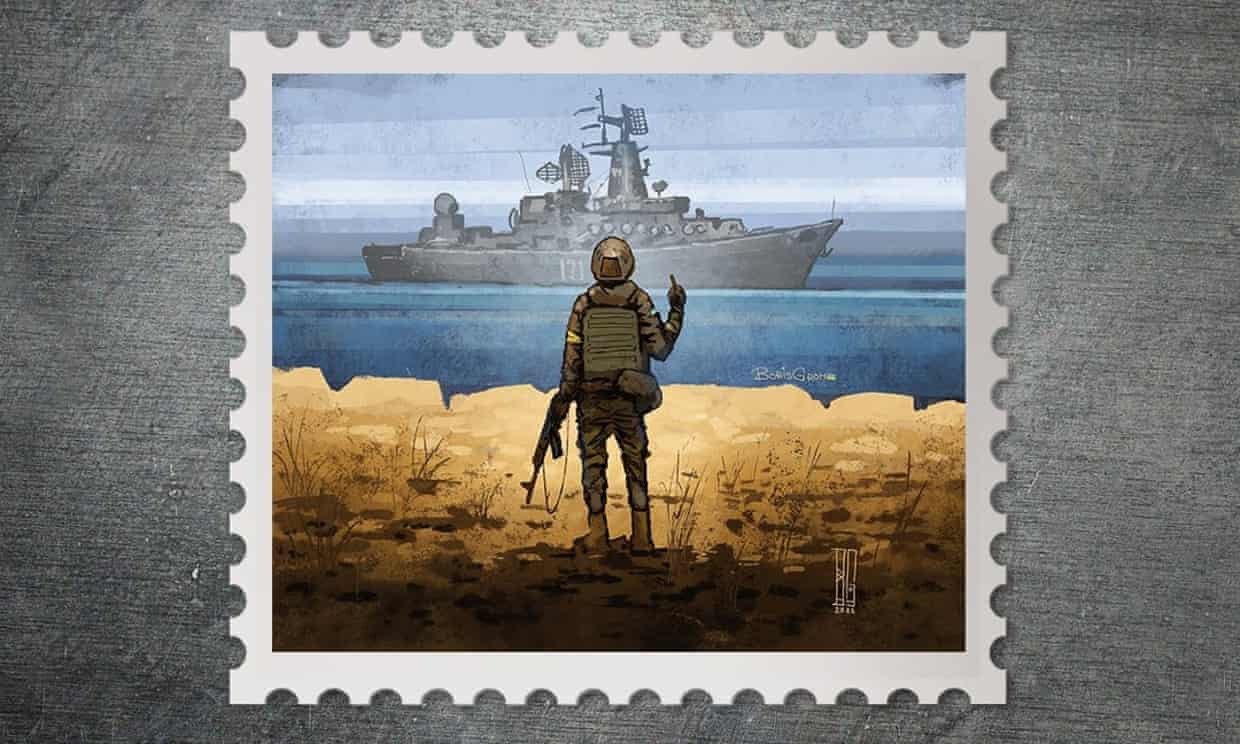

Yet here we are. You may recall the name Roman Gribov. He was one of several soldiers stationed on Snake Island in the Black Sea. When Russian warships began their part of the assualt of their sovereign neighbor, those warships communicated with Gribov, demanding that he and his fellow soldiers surrender. While staring down the barrel of the Russian Navy, Gribov offered up what is now an iconic response: “Russian warship… go fuck yourself!“

From there, the rebuttal took on meme status. Other attacks on Russian military assets were punctuated with versions of the phrase. Ukraine’s postal service created a commemorative stamp consisting of a sketch based on the quote. And thorughout the Western world, the phrase began showing up on t-shirts and other items.

Which perhaps partially explains why Gribov, through his family, is attempting to trademark the now iconic verbal middle finger.

Which perhaps partially explains why Gribov, through his family, is attempting to trademark the now iconic verbal middle finger.

WTR has learned that the soldier who uttered the ‘f*ck yourself’ phrase – with permission obtained from his family and the Ukrainian military – is seeking an EU trademark for the term (in both Cyrillic script and English). It was filed yesterday by Taras Kulbaba, founder and lawyer at Bukovnik & Kulbaba, and covers a variety of goods and services from clothing and bags to entertainment and NFTs.

With the safety of the soldier and his family in mind, Kulbaba took a relatively unusual approach when filing for the mark. “When we got in touch with both the military and his family with the idea for a trademark, they all approved but were also concerned that if the application had the family address, it would be dangerous and lead to people making their life hell,” he told WTR. “So after discussing it with both parties, we decided to file the application with the Snake Island address, because it was his place of domicile for quite a long period of time.”

A couple of comments on this. This Ukranian soldier is at the very least a badass and, for me frankly, something of a vulgar hero who perfectly fits my personal sensibilities. And it seems a great many people agree and wanted to spread his iconic message around. And, sure, some of those people are trying to make money off of the phrase.

But is any of this really deserving of trademark protection? You see this sort of thing with athletes sometimes, but at least they tend to have plans to use their marks in actual commerce. In this case, there was no plan to do so until others started making money off these words first...

[. ] I want to see this soldier and his family get good things coming to them, now more than ever. But the above still isn’t the purpose of trademark law. The idea here isn’t that you say something that goes viral and then you trademark it to turn it into a licensing business. Instead, trademarks are supposed to keep customer confusion at bay when it comes to a source of a good. I find it hard to believe that anyone is out there buying these t-shirts thinking that a Ukrainian soldier previously stationed on Snake Island made them in his off-time.

It’s all just kind of a depressing coda to an otherwise inspiring story. Ukrainian Soldier Moves To Trademark ‘Russian Warship, Go Fuck Yourself” Because Of Course

Timothy Geigner

Filed Under: euipo, go fuck yourself, russia, trademark, ukraine

READ MORE DETAILS >> https://www.techdirt.com/2022/03/18/ukrainian-soldier-moves-to-trademark-russian-warship-go-fuck-yourself-because-of-course/

FOR WHAT IT'S WORTH: Competition for Control of Fossil Fuels Creates Cross-Border Weaponized Conflict

Saudi Aramco’s 2021 profit more than doubles on higher oil prices

Saudi giant says its net income increased by 124 percent to $110bn in 2021, compared with $49bn in 2020.

(A strong rebound last year saw oil prices recover from their 2020 lows, and they have soared to highs not seen since 2014 this year, amid global supply shortages and Russia's invasion of Ukraine) [File: Bloomberg]

"Energy giant Saudi Aramco says its 2021 net profit soared by more than 120% due to higher crude oil prices, as global economic growth recovered from a pandemic induced downturn.

The announcement came on Sunday hours after Yemen’s Houthi rebels – against whom Saudi Arabia leads a military coalition – targeted several locations, including Aramco facilities, in cross-border armed drone attacks.

Aramco, Saudi Arabia’s cash cow, did not say if the attacks caused any damage.

“Aramco’s net income increased by 124 percent to $110bn in 2021, compared to $49bn in 2020,” the company said in a statement.

Aramco achieved a net income of $88.2bn in 2019 before the coronavirus pandemic hit global markets, resulting in huge losses for the oil and aviation sectors, among others.

A strong rebound last year saw oil prices recover from their 2020 lows, and they have soared to highs not seen since 2014 this year, amid global supply shortages and Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. . .

“Our strong results are a testament to our financial discipline, flexibility through evolving market conditions and steadfast focus on our long-term growth strategy,” Aramco President and CEO Amin Nasser said in a statement.

“Although economic conditions have improved considerably, the outlook remains uncertain due to various macroeconomic and geopolitical factors,” he said.

“But our investment plan aims to tap into rising long-term demand for reliable, affordable and ever more secure and sustainable energy,” he added.

“We recognise that energy security is paramount for billions of people around the world, which is why we continue to make progress on increasing our crude oil production capacity, executing our gas expansion program and increasing our liquids to chemicals capacity.”

Diversification of the economy

Since Mohammed bin Salman’s appointment as crown prince in 2017, Saudi Arabia has sought to diversify its oil-dominated economy. In February, the kingdom – one of the world’s top crude exporters – moved 4 percent of Aramco shares worth $80bn to the country’s sovereign wealth fund.

The transfer was also a sign that Saudi Arabia wants to further open up the oil giant and “crown jewel” of the Saudi economy, the Arab world’s largest.

The crown prince said last year that Aramco was in talks to sell a 1 percent stake to a foreign energy giant. . .

Brent crude is currently selling at more than $100 per barrel – in part due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

Russia is the world’s largest producer of gas and one of the biggest oil producers and is grappling with mounting Western sanctions.

Oil-rich Gulf countries, including Saudi Arabia, have so far resisted Western pressure to raise oil output to rein in prices, stressing their commitment to the OPEC+ alliance of oil producers, which Riyadh and Moscow lead."

READ MORE >> https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2022/3/20/saudi-aramco-says-annual-profit-more-than-doubled-in-2021

Sunday, March 20, 2022

BETTER CALL SOME PLUMBERS! . . .A Hit-Piece on Putin when both sides use Elusive "Leaks"

Intro: Here we go again with so-called "Hacker Gangs" using presuppositional conditional qualifiers like sometimes.

Leaked ransomware documents show Conti helping Putin from the shadows

Hacker gang sometimes acts in Russia’s interest, with ad hoc links to FSB, Cozy Bear.

For years, Russia’s cybercrime groups have acted with relative impunity. The Kremlin and local law enforcement have largely turned a blind eye to disruptive ransomware attacks as long as they didn’t target Russian companies. Despite direct pressure on Vladimir Putin to tackle ransomware groups, they’re still intimately tied to Russia’s interests. A recent leak from one of the most notorious such groups provides a glimpse into the nature of those ties—and just how tenuous they may be.

A cache of 60,000 leaked chat messages and files from the notorious Conti ransomware group provides glimpses of how the criminal gang is well connected within Russia. The documents, reviewed by WIRED and first published online at the end of February by an anonymous Ukrainian cybersecurity researcher who infiltrated the group, show how Conti operates on a daily basis and its crypto ambitions. They likely further reveal how Conti members have connections to the Federal Security Service (FSB) and an acute awareness of the operations of Russia's government-backed military hackers.

As the world was struggling to come to grips with the COVID-19 pandemic’s outbreak and early waves in July 2020, cybercriminals around the world turned their attention to the health crisis. On July 16 of that year, the governments of the UK, US, and Canada publicly called out Russia’s state-backed military hackers for trying to steal intellectual property related to the earliest vaccine candidates. The hacking group Cozy Bear, also known as Advanced Persistent Threat 29 (APT29), was attacking pharma businesses and universities using altered malware and known vulnerabilities, the three governments said.Days later, Conti’s leaders talked about Cozy Bear’s work and referenced its ransomware attacks. Stern, the CEO-like figure of Conti, and Professor, another senior gang member, talked about setting up a specific office for “government topics.” The details were first reported by WIRED in February but are also included in the wider Conti leaks. In the same conversation, Stern said they had someone “externally” who paid the group (although it is not stated what for) and discussed taking over targets from the source. “They want a lot about Covid at the moment,” Professor said to Stern. “The cozy bears are already working their way down the list.”

“They reference the setting up of some long-term project and seemingly throw out this idea that they [the external party] would help in the future,” says Kimberly Goody, director of cybercrime analysis at the security firm Mandiant. “We believe that's a reference to if law enforcement actions would be taken against them, that this external party may be able to help them with that.” Goody points out that the group also mentions Liteyny Avenue in St. Petersburg—the home to local FSB offices.

While evidence of Conti’s direct ties to the Russian government remains elusive, the gang’s activities continue to fall in line with national interests. “The impression from the leaked chats is that the leaders of Conti understood that they were allowed to operate as long as they followed unspoken guidelines from the Russian government,” says Allan Liska, an analyst for the security firm Recorded Future. “There appeared to have been at least some lines of communication between the Russian government and Conti leadership.”

FLASH-BANG 21st CENTURY CYBER ATTACKS: Intelligence Operations at The Edge of War

Why You Haven’t Heard About the Secret Cyberwar in Ukraine

Mr. Rid is a professor at Johns Hopkins University’s School of Advanced International Studies researching the risks of information technology

"For decades now, we have heard this refrain from the American defense establishment. We were warned that the next big state-on-state military confrontation could start with a flash-bang cyberattack: power outages in major cities, air traffic control going haywire, fighter jets bricked.

As Russia started amassing around 100,000 troops along its western and southern borders through 2021, Ukraine seemed to be the ideal battle space for such an apocalyptic scenario. The country has already seen some of the most brazen, shrewd and costly cyberattacks in history over the past eight years: hacks and election interference in 2014 as Russia annexed Crimea, remotely caused blackouts in 2015, devastating ransomware attacks in 2017.

In 2022 the war came but seemingly without the cyberapocalypse and waves of pummeling digital strikes we expected. “Cyberattacks on Ukraine Are Conspicuous by Their Absence,” headlined The Economista week into the war.

Such claims, however, are misleading. Cyberwar has come, is happening now and will most likely escalate. But the digital confrontation is playing out in the shadows, as inconspicuous as it is insidious. Several interlocking dynamics of cyberoperations in war stand out from what we have seen in Ukraine so far.

1

> First, some cyberattacks are meant to be visible and, in effect, distract from the stealthier and more dangerous sabotage. On Feb. 15 and 16, Ukrainian banks suffered major denial-of-service attacks, meaning their websites were rendered inaccessible. Western authorities swiftly attributed the attacks to Russia’s intelligence service, and Google is now helping protect 150 websites in Ukraine from such attacks. The Anonymous collective declared cyberwar against the Russian government soon after the attack and obtained a trove of data from a German subsidiary of Rosneft, a major Russian state-owned oil firm. Ukraine’s besieged government has embraced the idea of a crowdsourced I.T. army.

But these attacks and the decentralized volunteerism are simply a distraction. In fact, often the most damaging cyberoperations are covert and deniable by design. In the heat of war, it’s harder to keep track of who is conducting what attack on whom, especially when it is advantageous to both victim and perpetrator to keep the details concealed.

The day the Russian invasion started, ViaSat, a provider of high-speed satellite broadband services, suffered an outage. The services of Ka-Sat, one of its satellites, were seriously affected. The satellite covers 55 countries, predominantly in Europe, and provides fast internet connectivity. Among the affected Ka-Sat users: the Ukrainian armed forces, the Ukrainian police and Ukraine’s intelligence service.

ViaSat later revealed that the incident started in Ukraine and then spread, affecting 5,800 wind turbines in Germany and tens of thousands of modems across Europe as well. But details on the origin of this attack remain elusive, as does attribution. The Ukrainian security establishment, of course, has no interest in revealing the details of what might be a successful command-and-control attack in the middle of an existential war. Victor Zhora, a senior Ukrainian cybersecurity official, only generally acknowledged that the ViaSat incident caused “a really huge loss in communications” at the beginning of the war.

A week into the war, the Ukrainian newspaper Pravda published - Pravdapublished - the names, registration numbers and unit affiliations of 120,000 Russian soldiers fighting in Ukraine. Such large leaks can have powerful psychological effects on the exposed entity, which feels vulnerable and exposed.

Once again, though, the origin of the leak remains unclear. The material could have been procured from a Russian whistle-blower or taken through a network breach. Leaked files — in contrast to hacked machines — rarely contain clues for attribution. Some of the most consequential computer network breaches may stay covert for years, even decades. Cyberwar is here, but we don’t always know who is launching the shots.

2

> Second, cyberoperations in wartime are not as useful as bombs and missiles when it comes to inflicting the maximum amount of physical and psychological damage on the enemy. An explosive charge is more likely to create long-term harm than malicious software.

A similar logic applies to the coverage of hostilities and the psychological toll that media reporting can have on the public. There’s no bigger story than the violent effects of war: victims of missile attacks, families sheltering underground, residential buildings and bridges reduced to piles of smoking rubble. In comparison, the sensationalist appeal of cyberattacks is significantly lower. Largely invisible, they will struggle to break into the news cycle, their immediate effect greatly diminished.

We saw these dynamics play out in the Russian destructive malware “wiper” attacks of Feb. 23 and 24. Just hours before the invasion started, two cyberattacks hit Ukrainian targets: HermeticWizard, which affected several organizations, and IsaacWiper, which breached a Ukrainian government network. A third destructive malware attack was discovered on March 14, CaddyWiper, again targeting only some systems in a few unidentified Ukrainian organizations. It is unclear if these wiping attacks had any meaningful tactical effect against the victims, and the incidents never broke into the news cycle, especially when compared to the physical invasion of Ukraine by tanks and artillery.

3 >

Finally, without deeper integration within a broader military campaign, the tactical effects of cyberattacks remain rather limited. Thus far, we have no information on Russian computer network operators integrating and combining their efforts in direct support of traditional operations. Russia’s muted showing in the digital arena most likely reflects its subpar planning and performance on the ground and in the air. Close observers have been baffled by the Russian Army’s insufficient preparation and training, its lack of effective combined arms operations, its poor logistics and maintenance and its failure to properly encrypt communications.

Cyberwar has been playing a trick on us for decades — and especially in the past weeks. It keeps arriving for the first time, again and again, and simultaneously slipping away into the future. We’ve been stuck in a loop, doomed to repeat the same hackneyed debate, chasing sci-fi ghosts.

To harden our defenses, we must first recognize cyberoperations for what they have been, are and will be: an integral part of 21st-century statecraft.

The United States has a unique competitive advantage through its vibrant tech and cybersecurity industry. No other country comes even close to matching the U.S. public-private partnership in attributing and countering adversarial intelligence operations. These collaborative efforts must continue.

The contours of digital conflict are slowly emerging from the shadows, as digitally upgraded intelligence operations at the edge of war: espionage, sabotage, covert action and counterintelligence, full of deception and disinformation."

-

Flash News: Ukraine Intercepts Russian Kh-59 Cruise Missile Using US VAMPIRE Air Defense System Mounted on Boat. Ukrainian forces have made ...