Training materials reviewed

by The Intercept confirm that Google is offering advanced artificial

intelligence and machine-learning capabilities to the Israeli government

through its controversial “Project Nimbus” contract. The Israeli

Finance Ministry announced the contract

in April 2021 for a $1.2 billion cloud computing system jointly built

by Google and Amazon. “The project is intended to provide the

government, the defense establishment and others with an

all-encompassing cloud solution,” the ministry said in its announcement.

Google engineers have spent the time since worrying whether their

efforts would inadvertently bolster the ongoing Israeli military

occupation of Palestine. In 2021, both Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International

formally accused Israel of committing crimes against humanity by

maintaining an apartheid system against Palestinians. While the Israeli

military and security services already rely on a sophisticated system of computerized surveillance, the sophistication of Google’s data analysis offerings could worsen the increasingly data-driven military occupation.

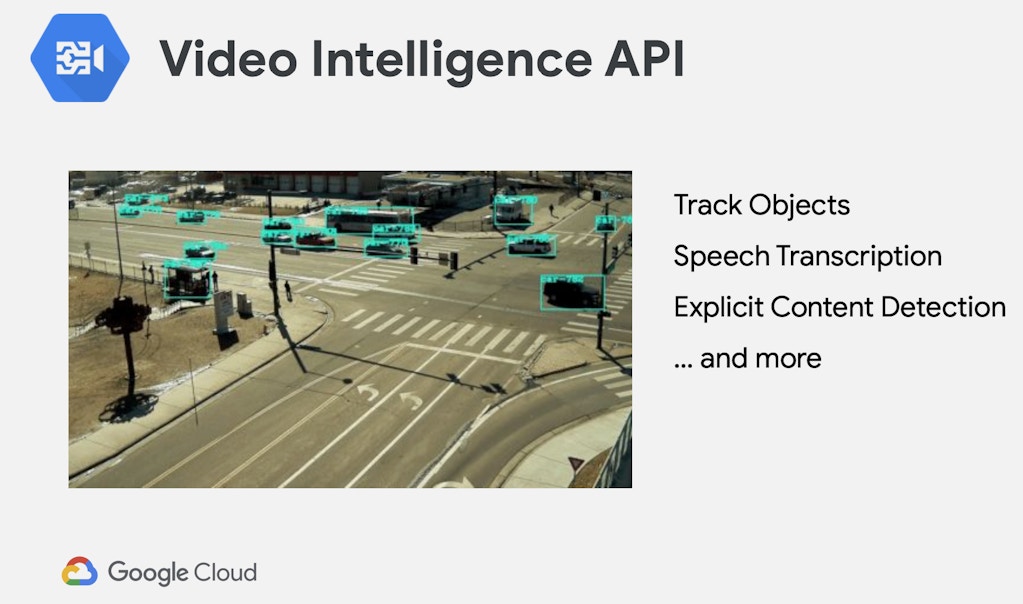

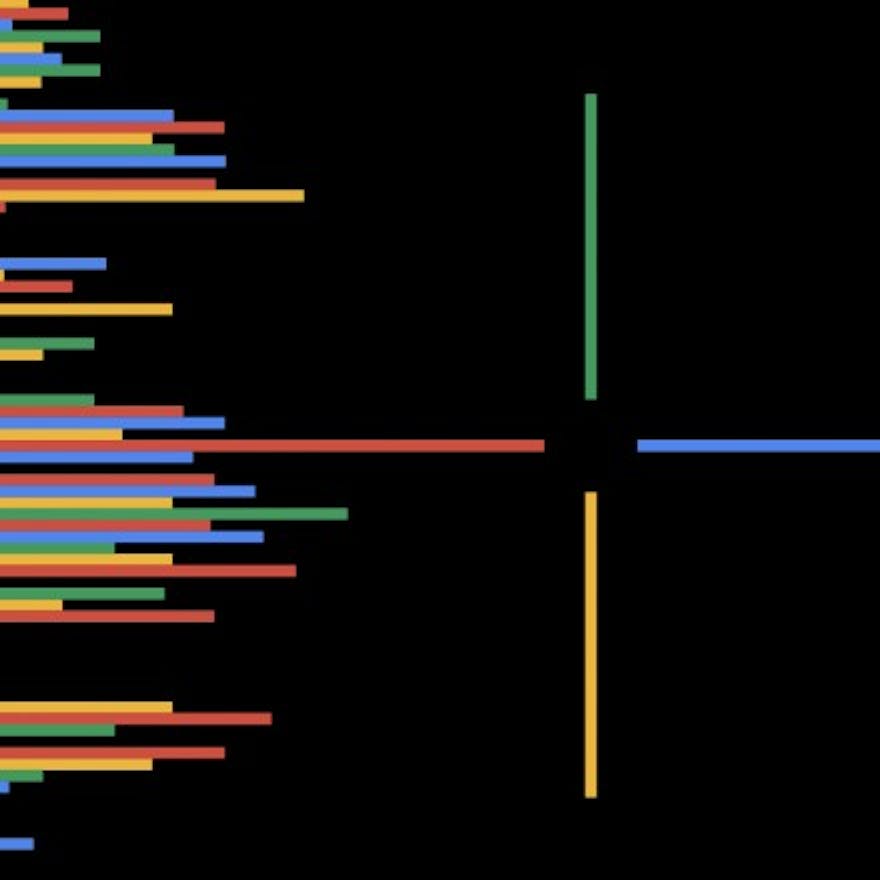

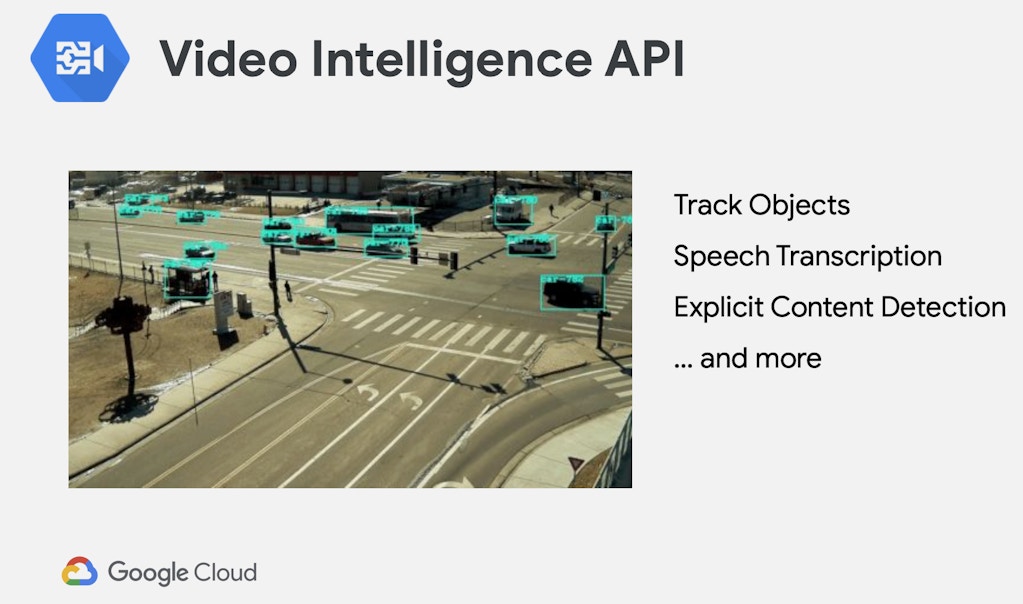

According to a trove of training documents

and videos obtained by The Intercept through a publicly accessible

educational portal intended for Nimbus users, Google is providing the

Israeli government with the full suite of machine-learning and AI tools

available through Google Cloud Platform. While they provide no specifics

as to how Nimbus will be used, the documents indicate that the new

cloud would give Israel capabilities for facial detection, automated

image categorization, object tracking, and even sentiment analysis that

claims to assess the emotional content of pictures, speech, and writing.

The Nimbus materials referenced agency-specific trainings available to

government personnel through the online learning service Coursera,

citing the Ministry of Defense as an example.

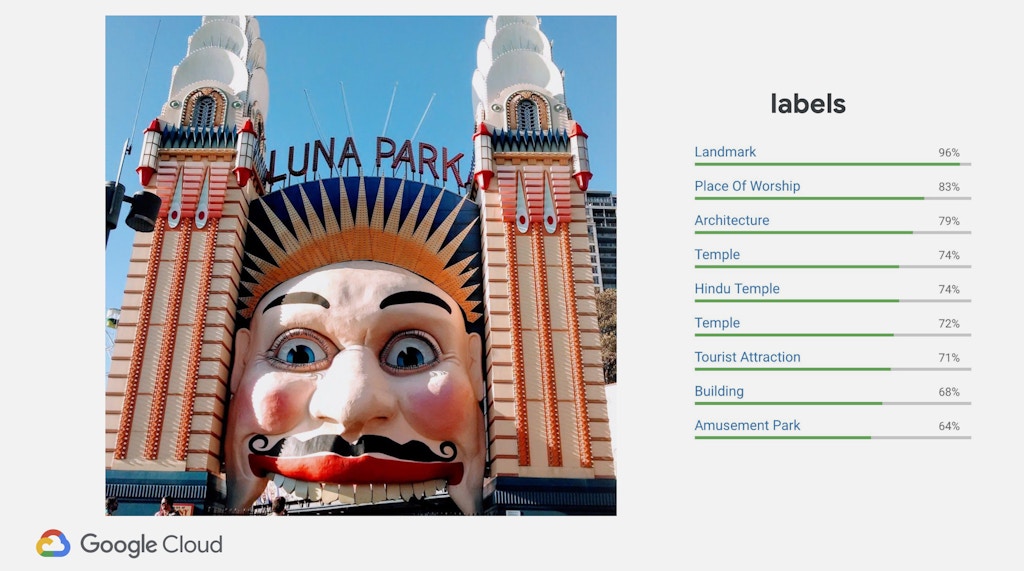

A slide presented to Nimbus users illustrating Google image recognition technology.

Credit: Google

Jack Poulson, director of the watchdog group Tech Inquiry, shared the

portal’s address with The Intercept after finding it cited in Israeli

contracting documents.

“The former head of Security for Google Enterprise — who now heads

Oracle’s Israel branch — has publicly argued that one of the goals of

Nimbus is preventing the German government from requesting data relating

on the Israel Defence Forces for the International Criminal Court,”

said Poulson, who resigned in protest from his job as a research

scientist at Google in 2018, in a message. “Given Human Rights Watch’s

conclusion that the Israeli government is committing ‘crimes against

humanity of apartheid and persecution’ against Palestinians, it is

critical that Google and Amazon’s AI surveillance support to the IDF be

documented to the fullest.”

Though

some of the documents bear a hybridized symbol of the Google logo and

Israeli flag, for the most part they are not unique to Nimbus. Rather,

the documents appear to be standard educational materials distributed to

Google Cloud customers and presented in prior training contexts

elsewhere.

Google did not respond to a request for comment.

The documents obtained by The Intercept detail for the first time the

Google Cloud features provided through the Nimbus contract. With

virtually nothing publicly disclosed about Nimbus beyond its existence,

the system’s specific functionality had remained a mystery even to most

of those working at the company that built it. In 2020, citing the same

AI tools, U.S Customs and Border Protection tapped Google Cloud to process imagery from its network of border surveillance towers.

Many of the capabilities outlined in the documents obtained by The

Intercept could easily augment Israel’s ability to surveil people and

process vast stores of data — already prominent features of the Israeli

occupation.

“Data collection over the entire Palestinian population was and is an

integral part of the occupation,” Ori Givati of Breaking the Silence,

an anti-occupation advocacy group of Israeli military veterans, told The

Intercept in an email. “Generally, the different

technological developments we are seeing in the Occupied Territories all

direct to one central element which is more control.”

The Israeli security state has for decades benefited from the country’s thriving research and development sector, and its interest in using AI to police and control Palestinians isn’t hypothetical. In 2021, the Washington Post reported on the existence of Blue Wolf,

a secret military program aimed at monitoring Palestinians through a

network of facial recognition-enabled smartphones and cameras.

“Living under a surveillance state for years taught us that all the

collected information in the Israeli/Palestinian context could be

securitized and militarized,” said Mona Shtaya, a Palestinian digital

rights advocate at 7amleh-The Arab Center for Social Media Advancement,

in a message. “Image recognition, facial recognition, emotional

analysis, among other things will increase the power of the surveillance

state to violate Palestinian right to privacy and to serve their main

goal, which is to create the panopticon feeling among Palestinians that

we are being watched all the time, which would make the Palestinian

population control easier.”

The educational materials obtained by The Intercept show that Google

briefed the Israeli government on using what’s known as sentiment

detection, an increasingly controversial and discredited form of machine

learning. Google claims that its systems can discern inner feelings

from one’s face and statements, a technique commonly rejected as

invasive and pseudoscientific, regarded as being little better than phrenology. In June, Microsoft announced that it would no longer offer

emotion-detection features through its Azure cloud computing platform —

a technology suite comparable to what Google provides with Nimbus —

citing the lack of scientific basis.

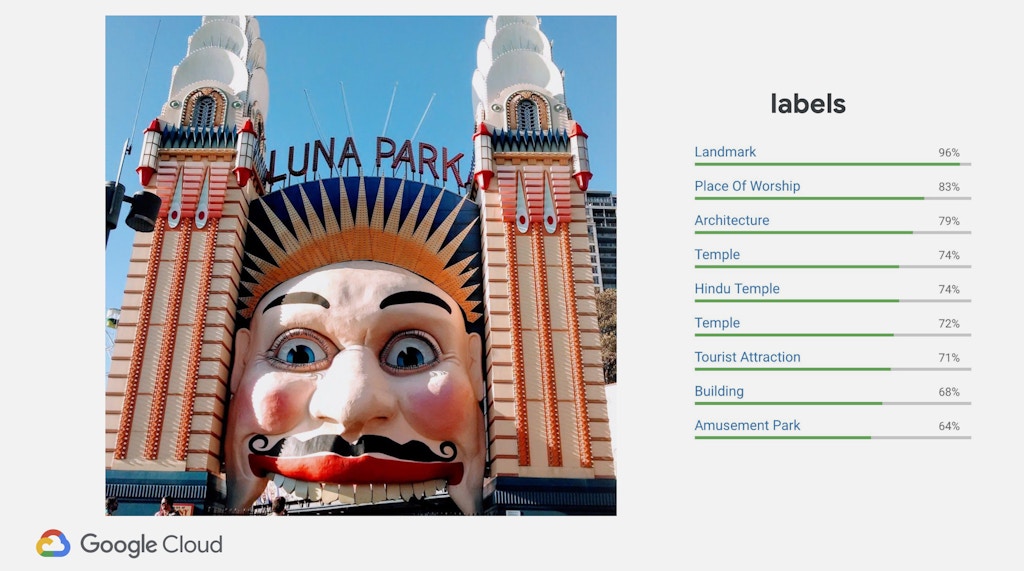

Google does not appear to share Microsoft’s concerns. One Nimbus presentation touted

the “Faces, facial landmarks, emotions”-detection capabilities of

Google’s Cloud Vision API, an image analysis toolset. The presentation

then offered a demonstration using the enormous grinning face sculpture

at the entrance of Sydney’s Luna Park. An included screenshot of the

feature ostensibly in action indicates that the massive smiling grin is

“very unlikely” to exhibit any of the example emotions. And Google was

only able to assess that the famous amusement park is an amusement park

with 64 percent certainty, while it guessed that the landmark was a

“place of worship” or “Hindu Temple” with 83 percent and 74 percent

confidence, respectively.

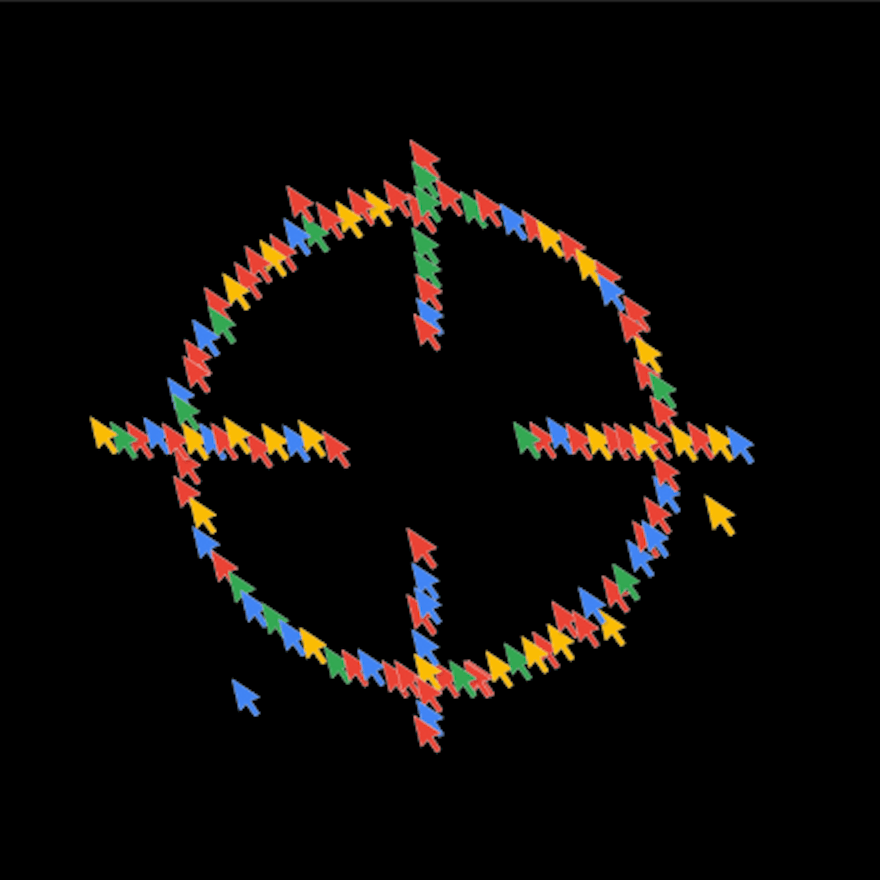

A slide presented to Nimbus users illustrating Google AI’s ability to detect image traits.

Credit: Google

Google workers who reviewed the documents said they were concerned by

their employer’s sale of these technologies to Israel, fearing both

their inaccuracy and how they might be used for surveillance or other

militarized purposes.

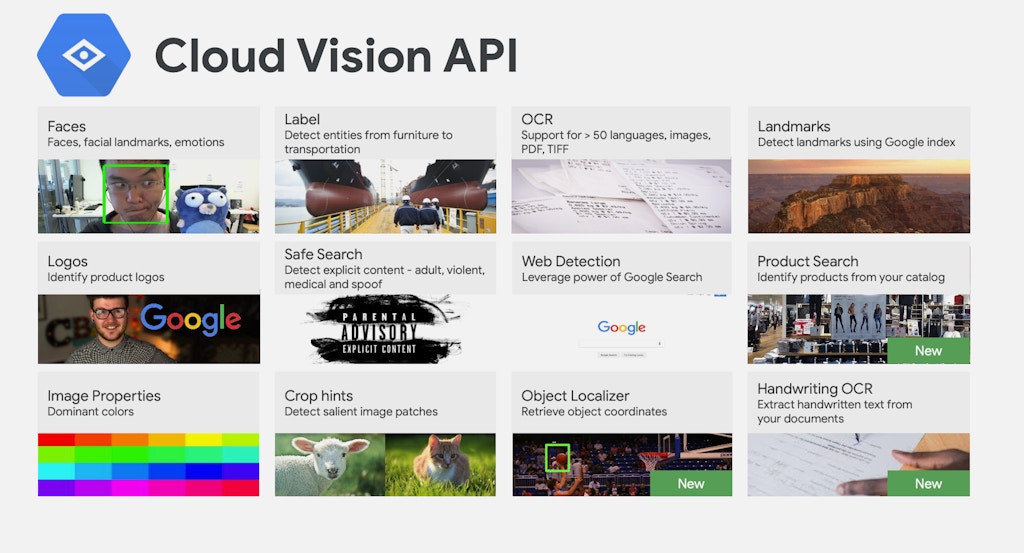

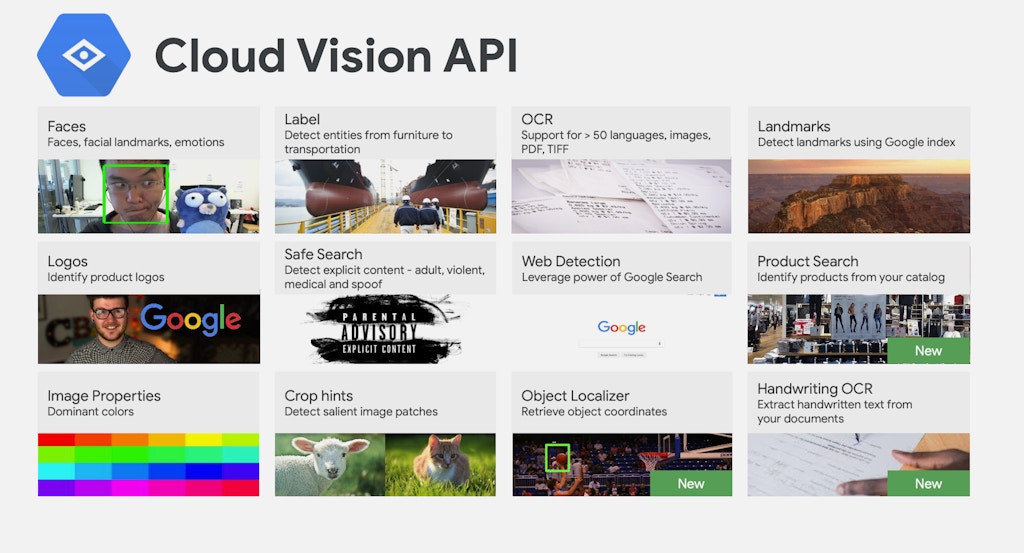

“Vision API is a primary concern to me because it’s so useful for

surveillance,” said one worker, who explained that the image analysis

would be a natural fit for military and security applications. “Object

recognition is useful for targeting, it’s useful for data analysis and

data labeling. An AI can comb through collected surveillance feeds in a

way a human cannot to find specific people and to identify people, with

some error, who look like someone. That’s why these systems are really

dangerous.”

A slide presented to Nimbus users outlining various AI features through the company’s Cloud Vision API.

Credit: Google

The employee — who, like other Google workers who spoke to The

Intercept, requested anonymity to avoid workplace reprisals — added that

they were further alarmed by potential surveillance or other

militarized applications of AutoML, another Google AI tool offered

through Nimbus. Machine learning is largely the function of training

software to recognize patterns in order to make predictions about future

observations, for instance by analyzing millions of images of kittens

today in order to confidently claim that it’s looking at a photo of a

kitten tomorrow. This training process yields what’s known as a “model” —

a body of computerized education that can be applied to automatically

recognize certain objects and traits in future data.

Training an effective model from scratch is often resource intensive,

both financially and computationally. This is not so much of a problem

for a world-spanning company like Google, with an unfathomable volume of

both money and computing hardware at the ready. Part of Google’s appeal

to customers is the option of using a pre-trained model, essentially

getting this prediction-making education out of the way and letting

customers access a well-trained program that’s benefited from the

company’s limitless resources.

“An

AI can comb through collected surveillance feeds in a way a human

cannot to find specific people and to identify people, with some error,

who look like someone. That’s why these systems are really dangerous.”

Cloud Vision is one such pre-trained model, allowing clients to

immediately implement a sophisticated prediction system. AutoML, on the

other hand, streamlines the process of training a custom-tailored model,

using a customer’s own data for a customer’s own designs. Google has

placed some limits on Vision — for instance limiting it to

face detection, or whether it sees a face, rather than recognition that

would identify a person. AutoML, however, would allow Israel to leverage

Google’s computing capacity to train new models with its own government

data for virtually any purpose it wishes. “Google’s machine learning

capabilities along with the Israeli state’s surveillance infrastructure

poses a real threat to the human rights of Palestinians,” said Damini

Satija, who leads Amnesty International’s Algorithmic Accountability

Lab. “The option to use the vast volumes of surveillance data already

held by the Israeli government to train the systems only exacerbates

these risks.”

Custom models generated through AutoML, one presentation noted, can

be downloaded for offline “edge” use — unplugged from the cloud and

deployed in the field.

That Nimbus lets Google clients use advanced data analysis and

prediction in places and ways that Google has no visibility into

creates a risk of abuse, according to Liz O’Sullivan, CEO of the AI

auditing startup Parity and a member of the U.S. National Artificial

Intelligence Advisory Committee. “Countries can absolutely use AutoML to

deploy shoddy surveillance systems that only seem like they work,”

O’Sullivan said in a message. “On edge, it’s even worse — think

bodycams, traffic cameras, even a handheld device like a phone can

become a surveillance machine and Google may not even know it’s

happening.”

In one Nimbus webinar reviewed by The Intercept, the potential use

and misuse of AutoML was exemplified in a Q&A session following a

presentation. An unnamed member of the audience asked the Google Cloud

engineers present on the call if it would be possible to process data

through Nimbus in order to determine if someone is lying.

“I’m a bit scared to answer that question,” said the engineer

conducting the seminar, in an apparent joke. “In principle: Yes. I will

expand on it, but the short answer is yes.” Another Google

representative then jumped in: “It is possible, assuming that you have

the right data, to use the Google infrastructure to train a model to

identify how likely it is that a certain person is lying, given the

sound of their own voice.” Noting that such a capability would take a

tremendous amount of data for the model, the second presenter added that

one of the advantages of Nimbus is the ability to tap into Google’s

vast computing power to train such a model.

“I’d be very skeptical for the citizens it is meant to protect that these systems can do what is claimed.”

A

broad body of research, however, has shown that the very notion of a

“lie detector,” whether the simple polygraph or “AI”-based analysis of

vocal changes or facial cues, is junk science. While Google’s reps

appeared confident that the company could make such a thing possible

through sheer computing power, experts in the field say that any

attempts to use computers to assess things as profound and intangible as

truth and emotion are faulty to the point of danger.

One Google worker who reviewed the documents said they were concerned

that the company would even hint at such a scientifically dubious

technique. “The answer should have been ‘no,’ because that does not

exist,” the worker said. “It seems like it was meant to promote Google

technology as powerful, and it’s ultimately really irresponsible to say

that when it’s not possible.”

Andrew McStay, a professor of digital media at Bangor University in Wales and head of the Emotional AI Lab,

told The Intercept that the lie detector Q&A exchange was

“disturbing,” as is Google’s willingness to pitch pseudoscientific AI

tools to a national government. “It is [a] wildly divergent field, so

any technology built on this is going to automate unreliability,” he

said. “Again, those subjected to them will suffer, but I’d be very

skeptical for the citizens it is meant to protect that these systems can

do what is claimed.”

According to some critics, whether these tools work might be of

secondary importance to a company like Google that is eager to tap the

ever-lucrative flow of military contract money. Governmental customers

too may be willing to suspend disbelief when it comes to promises of

vast new techno-powers. “It’s extremely telling that in the webinar PDF

that they constantly referred to this as ‘magical AI goodness,’” said

Jathan Sadowski, a scholar of automation technologies and research

fellow at Monash University, in an interview with The Intercept. “It

shows that they’re bullshitting.”

Google CEO Sundar Pichai speaks at the

Google I/O conference in Mountain View, Calif. Google pledges that it

will not use artificial intelligence in applications related to weapons

or surveillance, part of a new set of principles designed to govern how

it uses AI. Those principles, released by Pichai, commit Google to

building AI applications that are “socially beneficial,” that avoid

creating or reinforcing bias and that are accountable to people.

Photo: Jeff Chiu/AP

Google, like Microsoft, has its own public list of “

AI principles,”

a document the company says is an “ethical charter that guides the

development and use of artificial intelligence in our research and

products.” Among these purported principles is a commitment to not

“deploy AI … that cause or are likely to cause overall harm,” including

weapons, surveillance, or any application “whose purpose contravenes

widely accepted principles of international law and human rights.”

Israel, though, has set up its relationship with Google to shield it

from both the company’s principles and any outside scrutiny. Perhaps

fearing the fate of the Pentagon’s Project Maven,

a Google AI contract felled by intense employee protests, the data

centers that power Nimbus will reside on Israeli territory, subject to Israeli law and insulated from political pressures. Last year, the Times of Israel reported

that Google would be contractually barred from shutting down Nimbus

services or denying access to a particular government office even in

response to boycott campaigns.

Google employees interviewed by The Intercept lamented that the

company’s AI principles are at best a superficial gesture. “I don’t

believe it’s hugely meaningful,” one employee told The Intercept,

explaining that the company has interpreted its AI charter so narrowly

that it doesn’t apply to companies or governments that buy Google Cloud

services. Asked how the AI principles are compatible with the company’s

Pentagon work, a Google spokesperson told Defense One, “It means that our technology can be used fairly broadly by the military.”

“Google

is backsliding on its commitments to protect people from this kind of

misuse of our technology. I am truly afraid for the future of Google and

the world.”

Moreover, this

employee added that Google lacks both the ability to tell if its

principles are being violated and any means of thwarting violations.

“Once Google offers these services, we have no technical capacity to

monitor what our customers are doing with these services,” the employee

said. “They could be doing anything.” Another Google worker told The

Intercept, “At a time when already vulnerable populations are facing

unprecedented and escalating levels of repression, Google is backsliding

on its commitments to protect people from this kind of misuse of our

technology. I am truly afraid for the future of Google and the world.”

Ariel Koren, a Google employee who claimed earlier this year that she faced retaliation

for raising concerns about Nimbus, said the company’s internal silence

on the program continues. “I am deeply concerned that Google has not

provided us with any details at all about the scope of the Project

Nimbus contract, let alone assuage my concerns of how Google can provide

technology to the Israeli government and military (both committing

grave human rights abuses against Palestinians daily) while upholding

the ethical commitments the company has made to its employees and the

public,” she told The Intercept in an email. “I joined Google to promote

technology that brings communities together and improves people’s

lives, not service a government accused of the crime of apartheid by the

world’s two leading human rights organizations.”

Sprawling tech companies have published ethical AI charters to rebut

critics who say that their increasingly powerful products are sold

unchecked and unsupervised. The same critics often counter that the

documents are a form of “ethicswashing” — essentially toothless

self-regulatory pledges that provide only the appearance of scruples,

pointing to examples like the provisions in Israel’s contract with

Google that prevent the company from shutting down its products. “The

way that Israel is locking in their service providers through this

tender and this contract,” said Sadowski, the Monash University scholar,

“I do feel like that is a real innovation in technology procurement.”

To Sadowski, it matters little whether Google believes what it

peddles about AI or any other technology. What the company is selling,

ultimately, isn’t just software, but power. And whether it’s Israel and

the U.S. today or another government tomorrow, Sadowski says that some

technologies amplify the exercise of power to such an extent that even

their use by a country with a spotless human rights record would provide

little reassurance. “Give them these technologies, and see if they

don’t get tempted to use them in really evil and awful ways,” he said.

“These are not technologies that are just neutral intelligence systems,

these are technologies that are ultimately about surveillance, analysis,

and control.”

.jpg)