Ukraine the world’s biggest arms importer; United States’

dominance of global arms exports grows as Russian exports continue to

fall

Photo: US Air Force/Staff Sgt. Alexander Cook

(Stockholm,

10 March 2025)

Ukraine became the world’s largest importer of major

arms in the period 2020–24, with its imports increasing nearly 100 times

over compared with 2015–19.

European arms imports overall grew by 155% between the same periods, as states responded to Russia’s

invasion of Ukraine and uncertainty over the future of US foreign

policy.

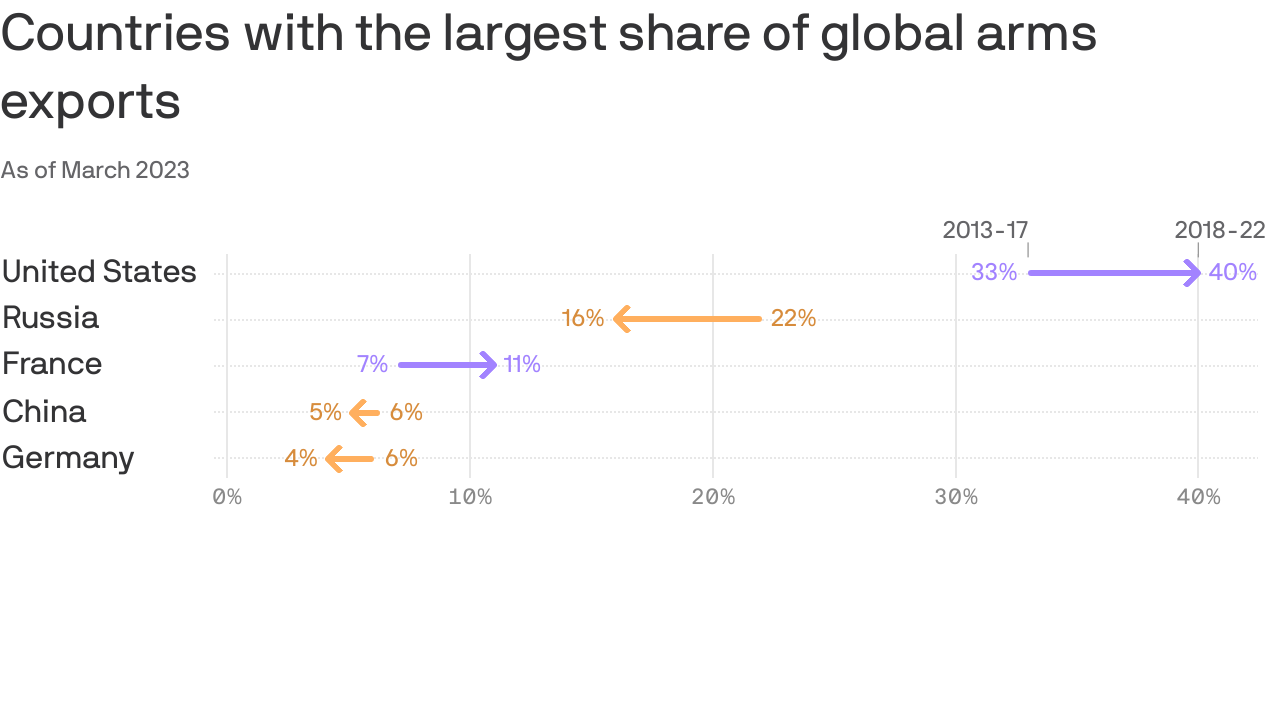

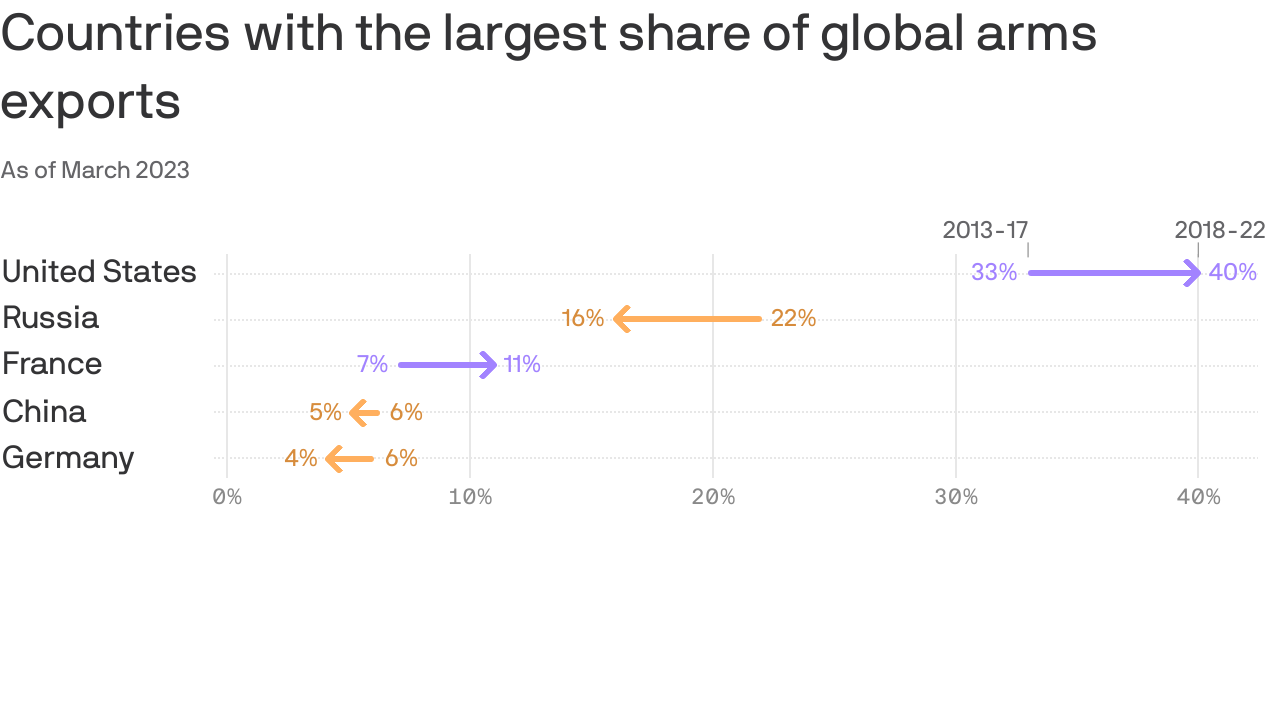

The United States further increased its share of global arms

exports to 43%, while Russia’s exports fell by 64%,

according to new data on international arms transfers published today by

the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), available

at www.sipri.org.

Read this press release in Catalan (PDF), French (PDF), Spanish (PDF) or Swedish (PDF).

Download the SIPRI Fact Sheet.

Last June, the Kyiv School of Economics’ KSE Institute and the

Yermak-McFaul International Working Group on Russian Sanctions

discovered that much of Russia’s weaponry, including ballistic and

cruise missiles, uses electronic components from the US, UK, Germany,

Netherlands, Japan, Israel and China, obtained by roundabout routes and

with the connivance of Chinese traders.

The arms trade sometimes involves unlikely actors. Ukraine’s Come

Back Alive is probably the only NGO in the world supplying drones,

rocket launchers and other heavy weapons to troops with government

authorisation. Other NGOs supply tablets to be used for artillery

guidance, body armour and anything else that makes life easier for

soldiers (6).

A wealth of new equipment is flooding the arms market. Drones are now

an indispensable part of military arsenals, and use of satellite

systems is becoming widespread; the US has a sizeable lead in this area

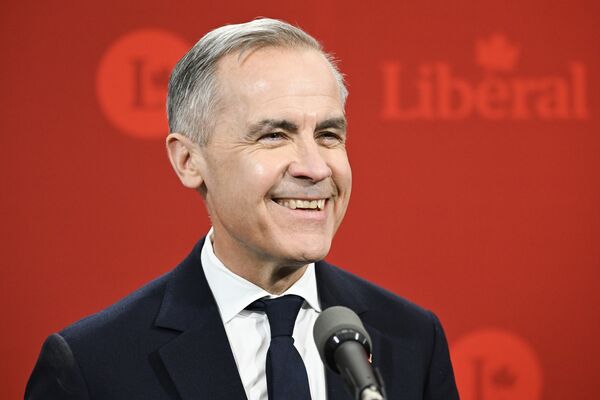

How the Ukraine war increased U.S. dominance of the global arms trade

U.S.

arms exports reached 43 percent of the worldwide total as Ukrainian

imports skyrocketed following the Russian invasion, according to

research by SIPRI.

By Adam Taylor

Global military spending rose for an eighth consecutive year in 2022

to a post-cold war peak of $2.24trn or 2.2% of global GDP, according to

the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI). French

army chief of staff General Pierre Schill has warned that ‘major wars

are back, and once more becoming a favoured way of settling differences’ (1).

Things started to get out of control when Russia annexed Crimea in

2014, and later parts of the Donbass. Since then the world has been

rearming. Defence industries have stepped up production and are

competing for export market share. Russia has pulled out of several arms

treaties and its 2024 defence budget is up nearly 70% year on year,

back to 1980s levels. Finance minister Anton Siluanov says it includes

‘everything needed for the front, everything needed for victory’. The

10.8trn roubles ($120bn), around 6% of GDP, will be used to accelerate

production of munitions, tanks and drones, pay troops and compensate the

families of those killed in action.

Russia was once the world’s second largest arms supplier (after the

US), accounting for 20% of global sales, mostly to Asia, the Middle East

and Africa, but has exported little since 2022. Its industry is

currently busy supplying its own army in Ukraine, where more munitions

and equipment have been lost or expended than at any time since the

second world war. Russia is estimated to have fired more than two

million shells in Ukraine in 2023, twice as many as in 2022, and the

Dutch defence analysis website Oryx says it has lost 10,000 military

land vehicles (damaged or destroyed). Western, especially US, sanctions

have also prevented major Russian deals with the Philippines (Mil Mi-17

helicopters), Indonesia (Sukhoi Su-35 fighters) and Kuwait (T-90 tanks).

Nor will there be any orders from former Warsaw Pact members or from

the Baltic states, which have joined NATO. These countries too are

rearming. Between 2014 and 2022 Lithuania’s defence spending rose by

270%, Latvia’s by 173%. The defence budgets of Finland, Hungary,

Slovakia, Romania, Poland and the Czech Republic have also soared.

Poland now spends 4% of GDP on defence and wants to double the size of

its army. It is buying Abrams tanks, HIMARS rocket launchers and Apache

helicopters from the US, and tanks and howitzers from South Korea, which

will make it a NATO heavyweight, alongside Germany.

Forget about ‘European preference’

Germany has yet to spend the $110bn allocated to the special fund for

modernising the Bundeswehr in 2022 but, showing little regard for

‘European preference’ (prioritising EU suppliers), has recently signed a

deal to buy US-Israeli Arrow missile defence systems and placed an

order for F-35 fighters with Lockheed Martin.

With Russia’s spare capacity taken up by the Ukraine war, France has

risen to second place in the global supplier rankings, with total

exports worth a record $30bn in 2022, thanks notably to Dassault’s sale

of Rafale fighters to the United Arab Emirates. Although these were

initially slow to sell (partly because of their price), they are now a

key part of France’s export lineup.

Alongside Europe’s major arms exporters – the UK, Germany, Italy and

Spain – new actors are emerging. Profiting from the ‘Ukraine effect’,

South Korea, already one of the world’s top ten producers, is openly

aiming for fourth place in the export rankings after France and Russia (2).

‘Ukraine today, East Asia tomorrow’

Japan, though uncomfortable with the idea of rearmament, fears that

‘Ukraine today may be East Asia tomorrow’, as prime minister Fumio

Kishida put it. Japan is worried by growing tensions between China and

the US, its close ally since 1945, and has decided to abandon pacifism (3).

Its new national security strategy highlights the ‘unprecedented

challenge’ posed by China’s regional ambitions. Its defence budget (just

over $50bn in 2023), has until now been capped at a notional 1% of GDP

but is due to rise to 2% by 2027. This will make Japan a regional

heavyweight and a new client for arms dealers. The US has already

promised Tomahawk long-range cruise missiles, until now restricted to

the UK and Australia.

Several Eastern European countries, including Poland, have given

Ukraine some of their older, often Soviet-era, equipment. Slovakia’s

arms industry, dormant since the cold war due to a lack of customers, is

now producing self-propelled howitzers, some of which are intended for

Ukraine, the rest for its own army. They are being promoted as cheaper

and more up to date than the French equivalent, the Caesar (4).

Major wars are back, and once more becoming a favoured way of settling differences

General Pierre Schill

France spent $2.2bn on munitions in 2023, partly to rebuild its own

stocks, depleted by the supply effort to Ukraine. Its 2024 defence

budget of $51.7bn is up 7.5% year on year. According to a National

Assembly report, it is, with Germany and the UK, among the countries

that have done the most to ‘give Ukraine the means to stand up to the

Russian army’ (5), with total aid worth $3.5bn, including transfers of artillery, armoured vehicles, shells and missiles, and training.

France also makes a large contribution to the European Peace

Facility, an off-budget fund established by the EU mainly to fund

actions such as providing defence equipment to Ukraine. Like the other

countries involved, France regularly repeats that supplying weapons to a

country that has been attacked and is exercising its legitimate right

of self-defence does not make it a party to the conflict. However, it

hopes its own arms industry will profit from the current situation.

‘The right thing to do’

Ethics and morality are secondary considerations in the arms

business. Last June, the US finally agreed to send cluster munitions to

Ukraine – ‘a very difficult decision’, Joe Biden maintained, even if it

was ‘the right thing to do’. Over 120 countries (not including the US,

Russia or Ukraine) have signed a convention banning them, because they

kill indiscriminately and claim many civilian lives long after the

fighting has ceased

Another example is the political whitewashing of Viktor Bout, a Russian arms dealer who inspired the film Lord of War

(2005). Bout spent 15 years in prison in the US but in December 2022

was exchanged for Brittney Griner, a US basketball player convicted in

Russia of smuggling and possessing cannabis. In July 2023 Bout was

elected to the legislative assembly of Russia’s remote Ulyanovsk oblast,

as a member of the ‘opposition’ Liberal Democratic Party of Russia.

Last June, the Kyiv School of Economics’ KSE Institute and the

Yermak-McFaul International Working Group on Russian Sanctions

discovered that much of Russia’s weaponry, including ballistic and

cruise missiles, uses electronic components from the US, UK, Germany,

Netherlands, Japan, Israel and China, obtained by roundabout routes and

with the connivance of Chinese traders.

The arms trade sometimes involves unlikely actors. Ukraine’s Come

Back Alive is probably the only NGO in the world supplying drones,

rocket launchers and other heavy weapons to troops with government

authorisation. Other NGOs supply tablets to be used for artillery

guidance, body armour and anything else that makes life easier for

soldiers (6).

A wealth of new equipment is flooding the arms market. Drones are now

an indispensable part of military arsenals, and use of satellite

systems is becoming widespread; the US has a sizeable lead in this area.

There are tools for exploring the deep seabed (monitoring submarine

cables, prospecting for polymetallic nodules) (7)

as well as hypersonic missiles (a field led by the US and Russia),

which are likely to be of interest to a growing number of militaries.

There is equipment used to mount cyberattacks and defend against them,

for information warfare or to protect telecoms networks. And of course,

arms manufacturers are hard at work developing the next generation of

tanks, fighter aircraft and ships for 2035-45.