A Clockwork Orange at 50: Stanley Kubrick’s biggest, boldest provocation

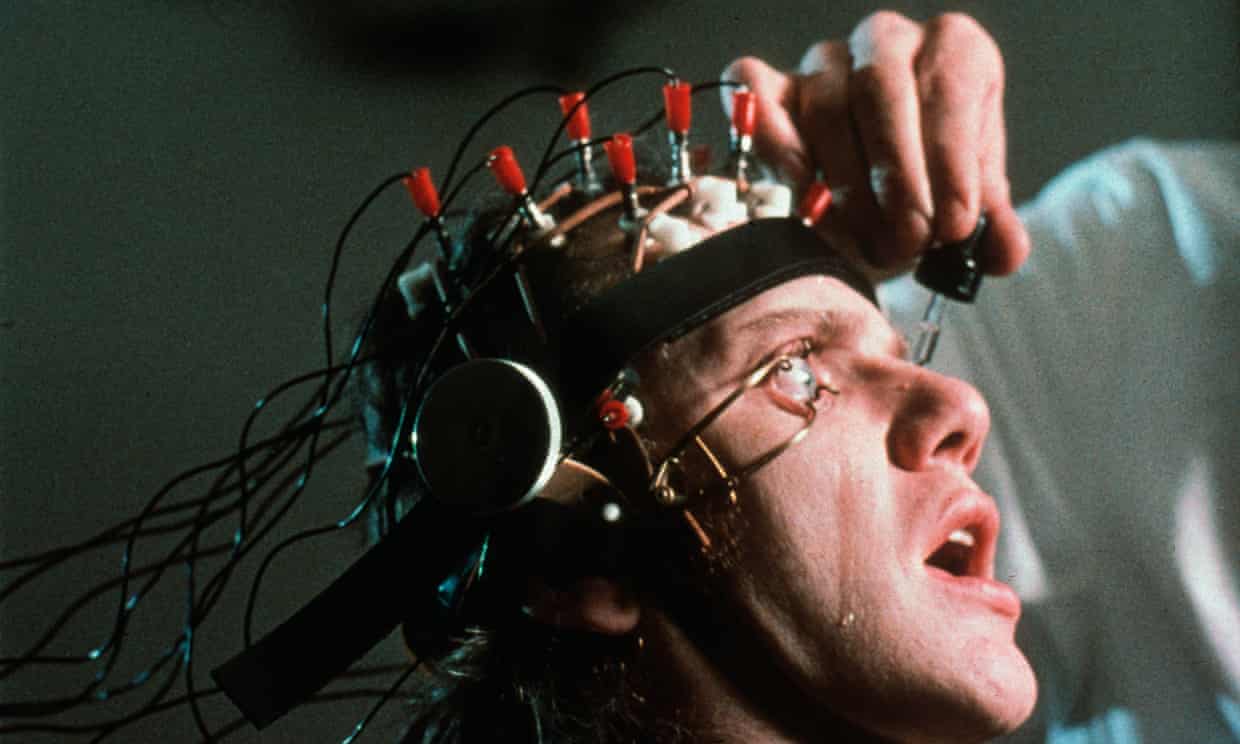

The controversial 1971 adaptation of Anthony Burgess’s button-pushing novel remains both utterly repellent and utterly compelling

Scott Tobias writes, ". . the film warns of a society lost to authoritarian rule, where an experimental campaign to curb criminal behavior leads to a deplorable form of social engineering. But Kubrick doesn’t limit himself to that issue alone, and as his agenda expands, so do the possible sticking points for an audience.

The backdrop for A Clockwork Orange is loaded with the interior bric-a-brac of its own period, like projecting the hippest, least comfortable living rooms of the early 70s would gain a permanent foothold. But there’s a key tension here between technological advancement and societal decay: for the elite, there are sports cars and modern homes, but for everyone else, apartment buildings and other public spaces crumble from neglect, leaving packs of young marauders to scavenge sick pleasures from “a bit of ultra-violence” and “a little of the old in-out, in-out”. Kubrick does not need to press much to suggest the root of their destructive impulses.

"Throughout his career, Stanley Kubrick never cared much about ingratiating himself to the audience, so it’s an achievement that A Clockwork Orange, his controversial adaptation of Anthony Burgess’ 1962 novel, is the most repellent film of his career. That’s not to say it isn’t an audacious and frequently brilliant film, but watching it can feel like getting into a 136-minute argument – with Kubrick, with yourself, and with a society that wrestles imperfectly (and often unjustly and tragically) with issues of law-and-order and individual rights. There’s something here to infuriate people on both ends of the political spectrum, and even if you accept it as a satire that has no ideological allegiances, that can be infuriating, too. And this is to say nothing of its extreme unpleasantness.

Yet we should neither run from difficult arguments nor hide from art that confronts us as seriously as Kubrick always did, and while A Clockwork Orange has settled into the pop-culture firmament – multiple references in classic episodes of The Simpsons will do that to a film – it still feels dangerous and vital 50 years later. As his previous work, 2001: A Space Odyssey, has settled appropriately as the great monolith of screen science fiction, A Clockwork Orange continues to be a moving target, liable not only to provoke you differently at different points in your life, but also from scene to scene. If it were released today, it would be a Three Mile Island-level event for the take industry . . .

[...] Every layer of A Clockwork Orange is its own nasty provocation, including the dispute Kubrick had with Burgess himself over a redemptive final chapter of the novel that wasn’t included in either the film or the American edition. No other director was as skilled as making films as texts to be examined and re-examined through myriad lenses for as long as the medium exists. His reputation as a perfectionist, on full display in every decision he makes here, belies the fact that his films exist to scramble your orientation and question your responses to them. They’re machines that expose our messy humanity."

TAKE A DEEP BREATH AND READ ON FOR MORE DETAILS: https://www.theguardian.com/film/2021/dec/19/a-clockwork-orange-at-50-stanley-kubrick

No comments:

Post a Comment