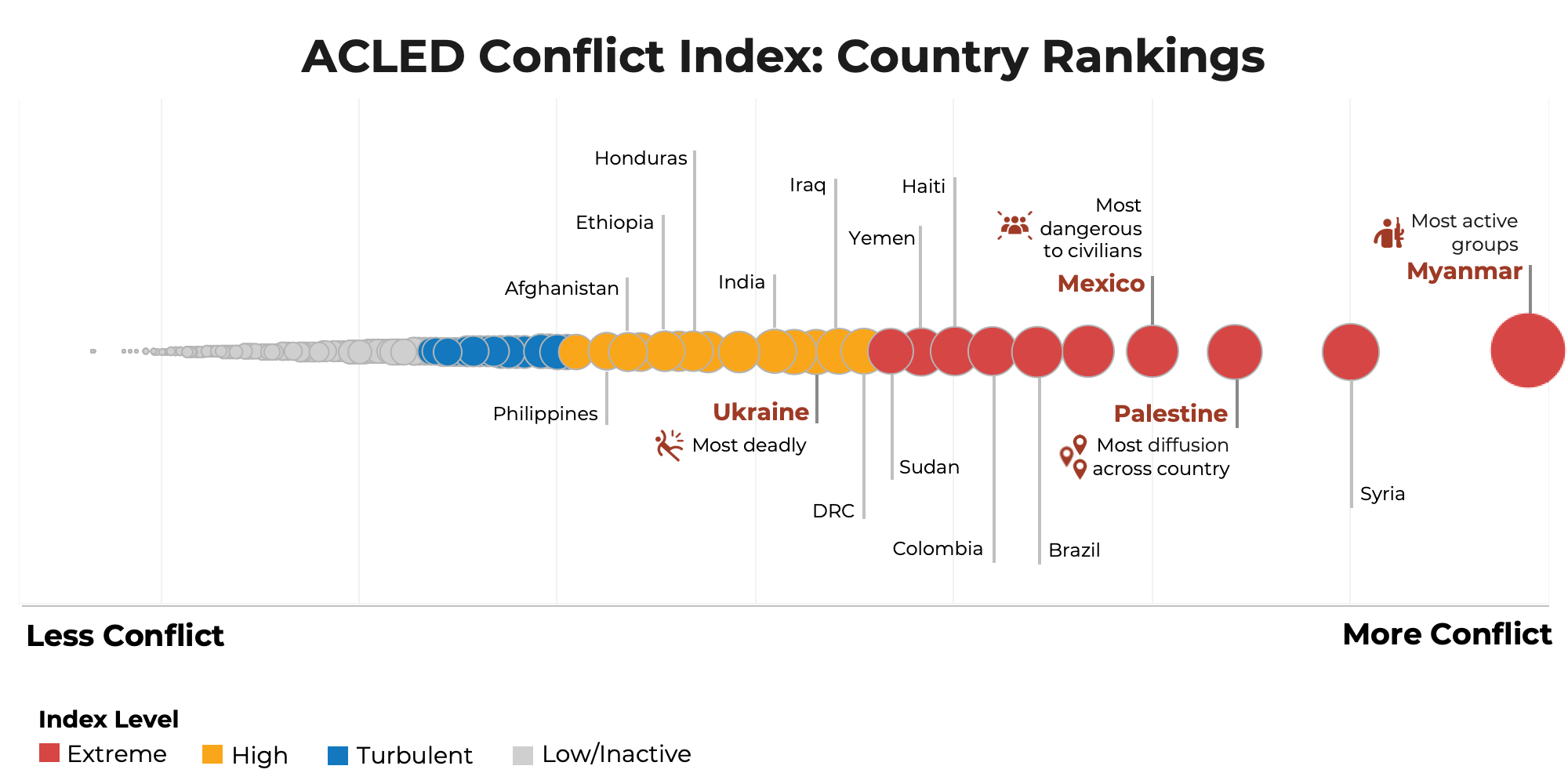

The ACLED Conflict Index assesses every country and territory in the world according to four indicators – deadliness, danger to civilians, geographic diffusion, and armed group fragmentation – based on analysis of political violence event data collected for the past year. The top 50 ranked countries and territories are experiencing extreme, high, or turbulent levels of conflict.

Explore the interactive map and overview below for more information about the Index’s findings and check the sidebar for a methodology explainer. Visit the Conflict Index Dashboard for access to further resources and data downloads.

ACLED Conflict Index

Ranking violent conflict levels across the world

Updated: January 2024

=========================================================================

How much conflict is occurring in the world?

Conflict is now widespread and pervasive: 12% more conflict occurred in 2023 compared to 2022, and ACLED records an increase of over 40% compared to 2020. One in six people live in an actively conflicted area. In 234 countries and territories covered by ACLED, the majority — 168 — saw at least one incident of conflict in 2023. Over 147,000 conflict events are recorded, and at least 167,800 fatalities.

Conflicts differ in their intensity, frequency, and form. For that reason, comparing event numbers may distort comparisons. Drawing on the latest data and patterns, the 2024 update to the ACLED Conflict Index assesses levels of conflict according to four key indicators: deadliness, danger to civilians, geographic diffusion of conflict, and armed group fragmentation.

Countries are ranked within each of these four indicators, and those positions determine the overall ranking on the Index (see Methodology sidebar for more). A country’s place on the Index represents its conflict level compared to other countries.

Conflict rates exist on a spectrum, and some level of conflict occurs in almost every country. The highest levels are found in the 50 countries highlighted in the Index list. These countries are categorized as ‘extreme,’ ‘high,’ or ‘turbulent.’ These top 50 ranked countries account for 97% of all conflict events recorded for the past 12 months. The extremely violent countries account for 40% of all conflict.

Of those 50 countries, Myanmar is the most violent overall and retains its position as the most ‘fragmented’ due to its hundreds of small militias formed to contest the government since the coup in 2021. Syria is the second most conflicted country due to multiple, overlapping conflicts which continue to occur within its borders. Palestine has conflict covering almost all of its territories and therefore ranks as the most ‘diffuse’ conflict. Palestine’s position rose since the last Index, entirely due to the extensive and deadly war with Israel primarily fought in Gaza. Mexico continues to be the most dangerous country for its citizens, as they are directly targeted by cartels in their violent competitions. Ukraine remains the most deadly as the armies on both the Ukrainian and Russian sides have lost tens of thousands of fighters — although, in the time since 7 October, Gaza specifically has the most overall fatalities.

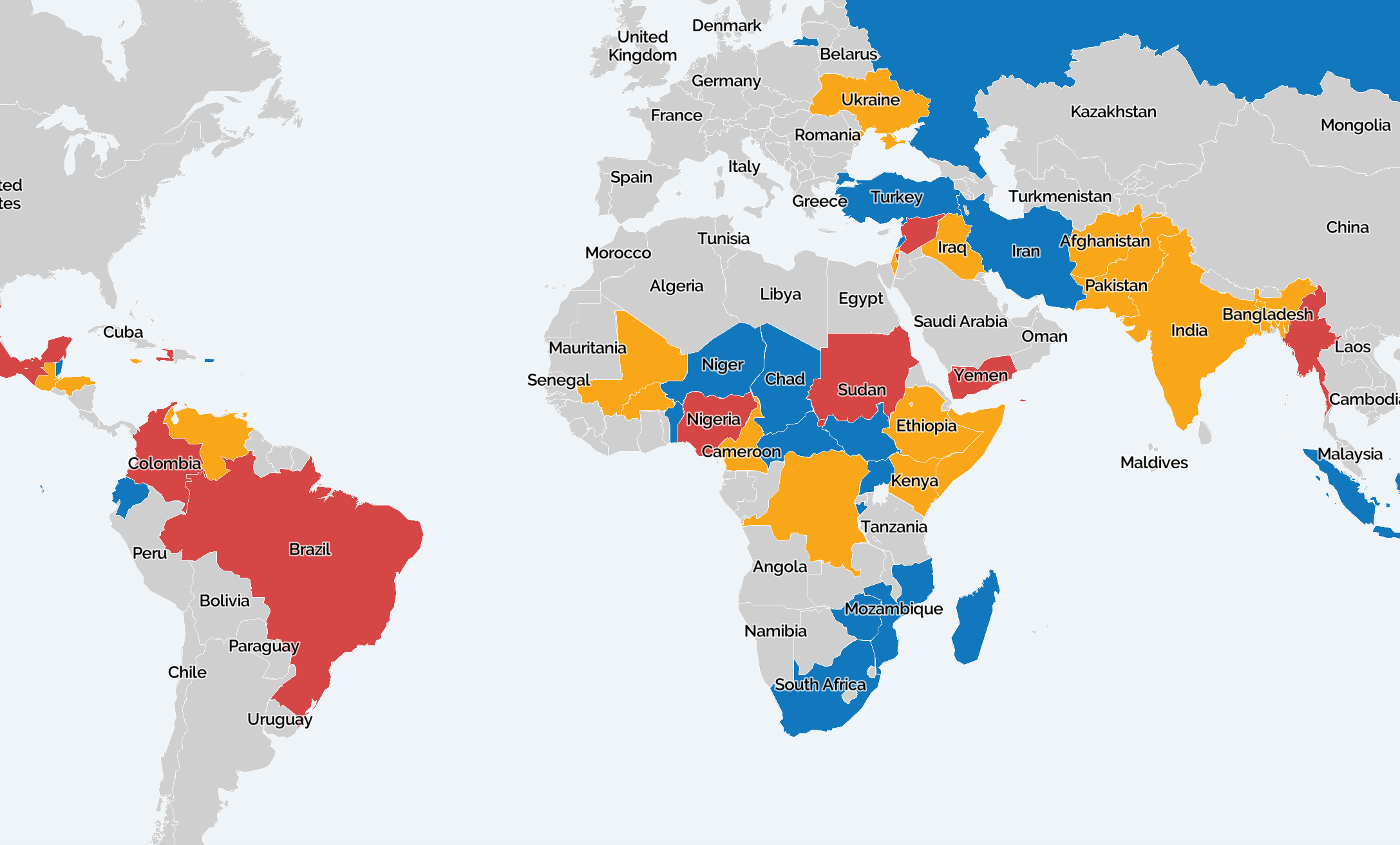

Where is conflict happening?

The 50 most violent countries and their rates of change are listed below. Of those countries with extreme violence, two are in Africa (Nigeria and Sudan), and Sudan continues to get worse as mass killings are a key feature of that conflict.

- Three countries are in the Middle East (Palestine, Yemen, and Syria), underscoring the depth of problems that persist in the region across decades. Myanmar is the sole Asian country with extreme violence, but it remains the most difficult conflict case in the world.

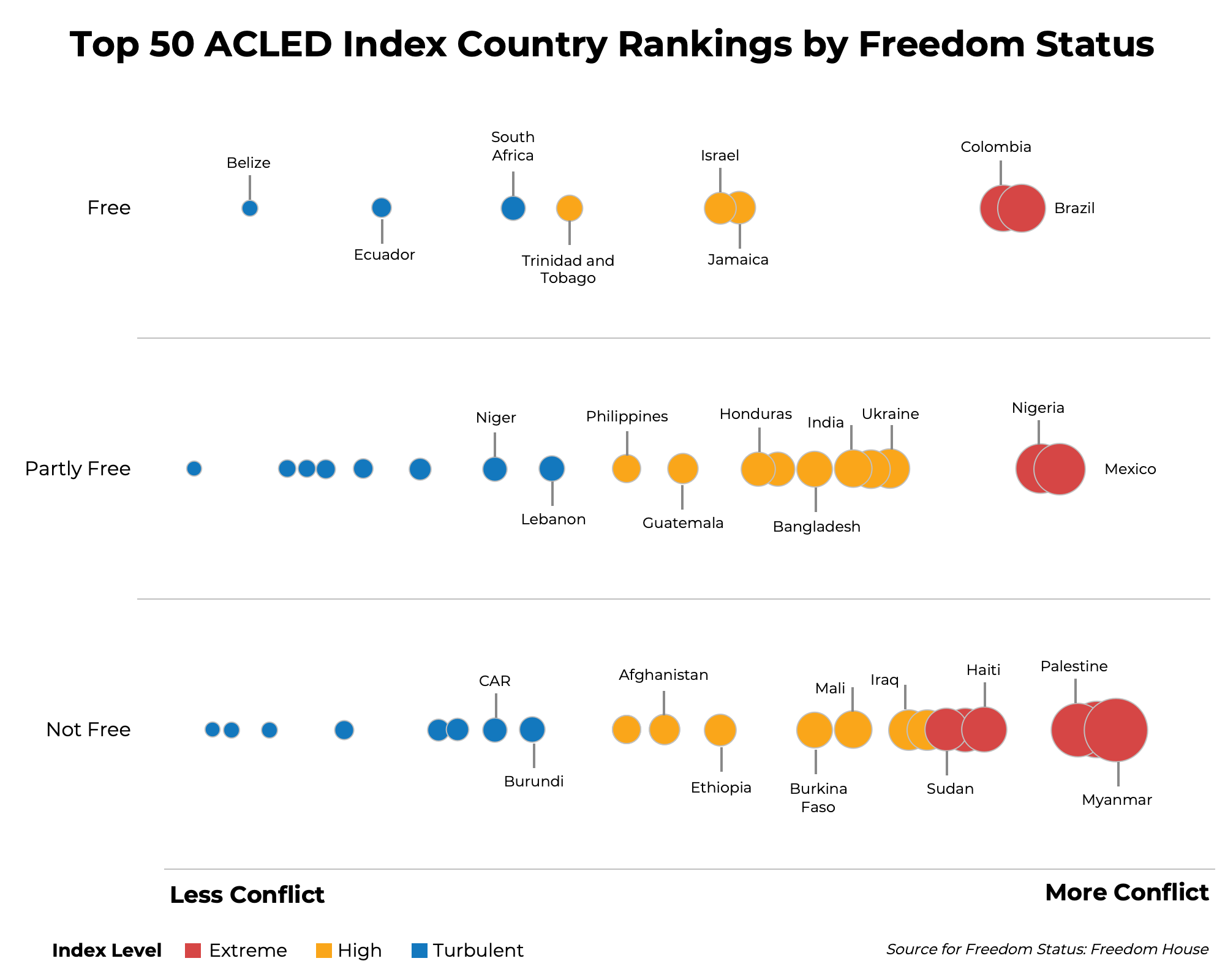

- Finally, four of the 10 extremely violent places are in Latin America (Mexico, Brazil, Colombia, and Haiti); barring Haiti, all are also considered relatively stable democracies and market economies despite being riddled with gangs, contested authorities, corruption, and violence against civilians. There are no large, traditional wars in these countries, but multiple, deadly, pervasive small conflicts.

These small conflicts and their characteristics continue to be the most persistent feature of instability across developing and more-developed countries. A key feature of these conflicts is the number of armed groups, and their agendas: several thousand militias and gangs operate across these conflicts, and their goals are often local authority and control. They do not seek to govern, speak for maligned or excluded groups, or transform the political system to be more democratic, fair, or representative. They are locked into a contest for power, where violence is the most effective tool available to them.

Click each column to sort results in the table below.

| Rank | Country | Index Level | Change Category | Change in Ranking |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Myanmar | Extreme | Consistently concerning | 0 |

| 2 | Syria | Extreme | Consistently concerning | 0 |

| 3 | Palestine | Extreme | Worsening | |

| 4 | Mexico | Extreme | Consistently concerning | |

| 5 | Nigeria | Extreme | Consistently concerning | 0 |

| 6 | Brazil | Extreme | Consistently concerning | 0 |

| 7 | Colombia | Extreme | Consistently concerning | |

| 8 | Haiti | Extreme | Worsening | |

| 9 | Yemen | Extreme | Consistently concerning | |

| 10 | Sudan | Extreme | Worsening | |

| 11 | Democratic Republic of Congo | High | Improving | |

| 12 | Iraq | High | Improving | |

| 13 | Ukraine | High | Improving | |

| 14 | Pakistan | High | Consistently concerning | |

| 15 | Mali | High | Consistently concerning | 0 |

| 15 | India | High | Consistently concerning | |

| 17 | Burkina Faso | High | Consistently concerning | |

| 17 | Bangladesh | High | Consistently concerning | |

| 19 | Kenya | High | Consistently concerning | |

| 20 | Honduras | High | Consistently concerning | 0 |

| 21 | Jamaica | High | Consistently concerning | |

| 22 | Ethiopia | High | Consistently concerning | |

| 22 | Israel | High | Worsening | |

| 24 | Guatemala | High | Consistently concerning | |

| 25 | Cameroon | High | Consistently concerning | |

| 25 | Afghanistan | High | Consistently concerning | |

| 27 | Somalia | High | Consistently concerning | |

| 27 | Philippines | High | Consistently concerning | |

| 27 | Venezuela | High | Consistently concerning | 0 |

| 30 | Trinidad and Tobago | High | Consistently concerning | |

| 31 | Lebanon | Turbulent | Consistent | |

| 32 | Burundi | Turbulent | Consistent | |

| 33 | South Africa | Turbulent | Consistent | |

| 34 | Niger | Turbulent | Improving | |

| 34 | Central African Republic | Turbulent | Consistent | 0 |

| 36 | Russia | Turbulent | Consistent | |

| 37 | South Sudan | Turbulent | Consistent | |

| 38 | Madagascar | Turbulent | Worsening | |

| 39 | Puerto Rico | Turbulent | Consistent | |

| 40 | Ecuador | Turbulent | Consistent | |

| 41 | Turkey | Turbulent | Consistent | |

| 42 | Uganda | Turbulent | Consistent | |

| 43 | Benin | Turbulent | Consistent | |

| 44 | Indonesia | Turbulent | Consistent | |

| 45 | Mozambique | Turbulent | Consistent | |

| 46 | Iran | Turbulent | Consistent | |

| 47 | Belize | Turbulent | Worsening | |

| 48 | Zimbabwe | Turbulent | Worsening | |

| 49 | Chad | Turbulent | Consistent | |

| 50 | Papua New Guinea | Turbulent | Worsening |

What does the Index tell us?

The world is getting far more violent in recent years: conflict event rates have increased by over 40% from 2020 through 2023; and increased 12% in 2023 from 2022 rates. But 2020 was a relatively less violent year compared to 2018-2019, when wars in both Afghanistan and Syria raged. Compared to those years, the increase in 2023 is still significant at an average of 20%.

Is conflict worsening or improving?

As of January 2024, 15 countries have seen improvements to their Index rankings during the five-year period between 2019 and 2023, and 16 have seen worsening levels of conflict.

- Sixteen countries have remained in the ‘extreme’ or ‘high’ conflict level categories consistently, with no change between 2019 and 2023.

- Overall, of the 50 countries ranked at the top of the Index, over half (42) are experiencing sustained or escalating levels of conflict compared to 2019.

In the six months between the mid-year update of the Index (July 2023) and the end of the year, eight countries have seen worsening levels of conflict, with three of those countries – Palestine, Haiti, and Sudan – moving into the ‘extreme’ conflict level category.

Ukraine decreased on the list. Why?

Ukraine’s position on the Index has decreased for two reasons. First, there are remarkable levels of stagnation in the Ukraine conflict, including in fatalities, active locations, and the fighting parties. Ukraine’s conflict is currently in a stage of attrition, with no sign of ending, and very little sign of change. Second, conflict in other countries is rising in multiple ways: in event frequency, conflict groups, and location under active conflict. While Ukraine’s conflict rate has stayed relatively stable and consistent, continued increases in other countries mean that it falls from ‘extreme’ to ‘high.’

Conflict rates and media attention are not correlated. Why?

Many conflicts do not garner sufficient attention, no matter how violent. These include Myanmar and Syria, which have ranked as the most violent countries in the Index for a year. In both cases, the conflicts are multiple, complicated, and enduring. Myanmar’s armed group resistance against the military junta persists, while Syria continues to battle with continuing violence in Idlib (the last anti-government holdout); continued Islamic State attacks in the east; Turkey attacking Kurdistan Workers’ Party (PKK) fighters in the north; Iraqi resistance forces attacking United States bases; Israeli strikes in Damascus; and continuing unrest in smaller corners of the country.

There are several reasons why conflict rates and media attention are not matched:

First, media attention is most frequently centered on conflicts that are internationally or ‘geopolitically’ relevant, meaning they have a resonance beyond the borders of the country in conflict, or they involve at least two governments (rather than internal conflicts).

The media covered both Gaza and Ukraine extensively because of the widespread interest in these conflicts and the threat of larger violence emanating from these contests. In Gaza, the conflict between Israel and Hamas is intense, very damaging for the population of Gaza, and has regional ramifications. Many journalists have been killed in bombings, but widespread coverage continues of Israeli activity. In Ukraine, the conflict involving Russia’s invasion of its sovereign neighbor has significant future implications for NATO and the European Union, other countries in Russia’s ‘near abroad,’ and the ability to prevent future invasions by a marauding state.

Second, most complex conflicts are difficult to report on, and increasingly, internal conflicts have multiple armed groups, competing agendas, and variable violent strategies. Many of the conflicts we see in the most extreme categories violate our typical understandings of conflict as civil wars, insurgencies, or terrorist events. Conflicts in Mexico, Brazil, and Colombia are complicated by cartels, pro-government gangs and anti-government groups: these groups are not trying to overtake the government or control territory to govern. They engage with the local police, and when they target government officials, it is often administrators like mayors and councilors. These militias seek to benefit from the existing political structure, and aim to have economic and social control over places and populations. The countries in both the ‘extreme’ and ‘high’ Index categories are very violent because so many of these militia groups exist, exposing large populations to violence in their competition between each other and civilians. While the media often expects revolution and mass repression from internal conflicts, most political violence looks very different.

Third, the threat to the media in some conflicts prevents full coverage, and victims, local organizations, or even governments provide information on the activities within conflicts. Not all conflict information is comparable in coverage, fairness, or accuracy, even when the environment allows for the free flow of information. The interest — and even biases — of audiences shape what kinds of information we receive.

How have conflicts changed?

Conflicts have become complex in some common ways.

There are few large, traditional wars now being fought, but many countries with several overlapping, concurrent conflicts.

The forms of conflict that are the most common around the world look more like the violence patterns in Mexico and Myanmar, and are less like traditional insurgencies where one group wrestles with a government for control or territory. They also host multiple conflicts that differ in both targets and intended outcomes, and these conflicts do not often overlap. This means that governments frequently find themselves fighting multiple conflicts at once, and communities are exposed to varied types of violence.

Violence in countries experiencing ‘extreme’ and ‘high’ conflict levels typically also involves many active armed, organized groups. These groups fight each other as frequently as they clash with government security forces. Militias, rather than rebels, increasingly play a leading role in these conflicts.

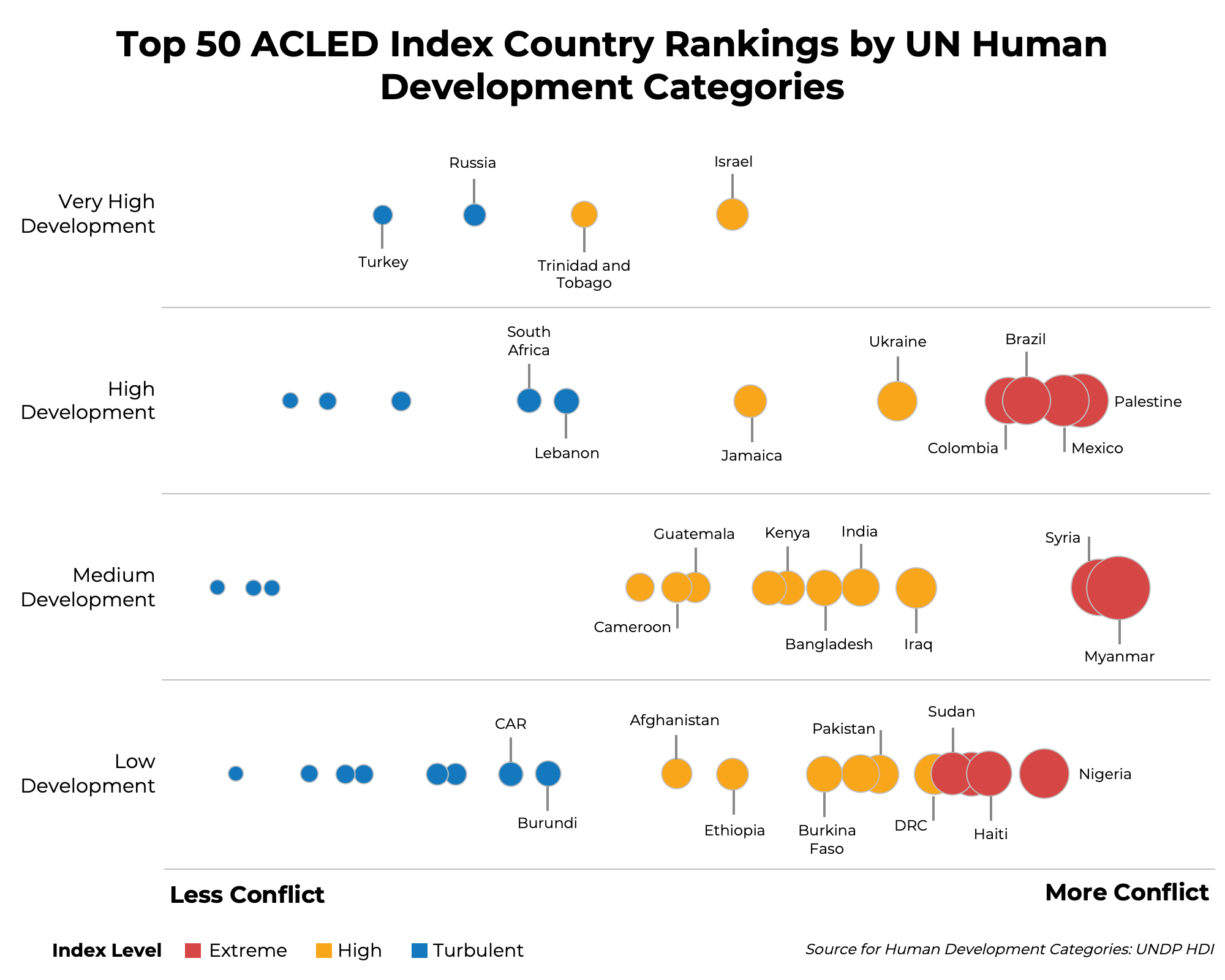

Conflict is growing fastest in middle-income, democratizing countries. Middle-income countries are experiencing the greatest rise in conflict. Poverty is not a precursor to conflict, and wealth is not a guarantee of peace. In the graphic below, the top 50 countries in the ACLED Conflict Index are placed across the UN Human Development Index. As this comparison demonstrates, many countries with ‘extreme’ or ‘high’ levels of conflict are places with high and sustained levels of economic and social development.

There will be an unprecedented number of elections in 2024, and over half the world’s population will participate in, or live in, a country experiencing an election. This will give rise to violent attacks against civilians and more targeted assaults and killings of local officials by armed groups.

Can the Index suggest what is to come?

In the past, this Index has highlighted a country’s conflict position as ‘worsening,’ and confirmed its increasing instability in subsequent updates.

For example, in July, Palestinian territories were noted as in ‘high’ conflict and having the world’s most extensive and diffuse violence; in this updated Index,

Palestine is now ‘extremely’ violent.

The Index aggregates several characteristics of violence that are sensitive to change, and this allows us to robustly assess the likely trajectory of conflict.

For example, the current Index suggests that Sudan and Haiti will likely worsen in the following six months, and Nigeria may improve. Yemen and Mexico are also likely to worsen.

ACLED produces monthly conflict forecasts at the national and subnational level in our Conflict Alert System (CAST).

This system is highly accurate as to the trajectory of events in very violent countries.

For example, on average over the last 6 months, CAST has predicted the number and type of events within 4% accuracy in half of the ‘extreme’ category countries: Brazil, Mexico, Yemen, Nigeria and Colombia.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------===============================================================

1st Special Forces Command (Airborne) Reaches a Milestone: The Evolution of the Nation's Premier Partnership Force | Article | The United States Army

1st Special Operations Command (1982-1990)

U.S. Army Special Forces Command (1990-2014)

Special Forces Soldiers assigned to USASFC deployed extensively during the 24-year history of the command, beginning with Operations DESERT SHIELD and DESERT STORM, and continuing through the 1990s in places such as the Balkans, Haiti, Somalia, and Liberia. Following the September 11, 2001, attacks on the U.S., USASFC forces were among the first on the ground in Afghanistan for Operation ENDURING FREEDOM and contributed extensively to the various other conflicts during the post-9/11 era. In doing so, they continued to demonstrate their global reach, and their ability to make an outsized impact on the battlefield.

1st Special Forces Command (2014 – Present)

Headquartered at Fort Liberty, North Carolina, the 1st Special Forces Command (Airborne) mission is to assign, equip, train, certify, and validate ARSOF and units to conduct global special operations in support of theater and national objectives. On order, 1st Special Forces Command (Airborne) deploys as the Army core of the Special Operations Joint Task Force headquarters to execute command and control of special operations and/or forces in support of global crisis response missions.

Following Maj. Gen. Rogers, 1st Special Forces Command (Airborne) was subsequently commanded by Major Generals James E. Kraft, Jr., Francis M. Beaudette, E. John Deedrick, Jr., John W. Brennan, Jr., and Richard E. Angle. Today, 1st Special Forces Command (Airborne) is commanded by Maj. Gen. Lawrence G. “Gil” Ferguson, who is assisted by Chief Warrant Officer Five Felix Mosqueda, the Command Chief Warrant Officer, and Command Sergeant Major David R. Waldo.

Learn more about Army Special Operations history at www.arsof-history.org.

No comments:

Post a Comment