Monday, November 08, 2021

City of Mesa, Arizona Opts for OVER-POLICING...LAPD Not so much

LAPD ended predictive policing programs amid public outcry. A new effort shares many of their flaws

How Operation Laser created a vicious cycle

Launched in 2011, Operation Laser (an acronym for Los Angeles Strategic Extraction and Restoration) got its name from what LAPD hoped it would do: extract “offenders” with the precision of a doctor using laser surgery to remove a tumor.

On its face, using a data-backed approach to remove a “tumor” may seem logical. The problem was, according to critics and experts, that the data the program ran on was malignant.

Operation Laser used historical information such as data on gun-related crimes, arrests, and calls to map out “problem areas” (called “laser zones”) and “points of interest” (called “anchor points”) for officers to focus their efforts on. A newly established group, the crime intelligence detail, worked to create chronic offender bulletins, assigning criminal risk scores to people based on arrest records, gang affiliation, probation and field interviews. Information collected during these policing efforts was again fed into computer software that further helped automate the department’s crime-prediction efforts.

Central to Operation Laser’s success, wrote Craig Uchida, the program’s architect at LAPD, in a research paper in 2012, was Palantir. The software, controversial for aiding US Immigration and Customs Enforcement in surveilling immigrants, made it easier and faster for the department to create chronic offender bulletins and put together information from various sources on people deemed suspicious or inclined to commit a crime, Uchida said.

But the picture of crime in LA the software drew up was based on calls for service, crime reports and information collected by officers, the documents show, creating a vicious loop.

> In 2019, the LAPD inspector general, Mark Smith, said the criteria used in the program to identify people likely to commit violent crimes were inconsistent.

[. . .] As the Guardian revealed on Sunday, one of the locations that Operation Laser targeted was the Crenshaw district, where the rapper Nipsey Hussle was based. Hussle had long complained about policing in his neighborhood, saying in a 2013 interview that LAPD officers “come hop out, ask you questions, take your name, your address, your cell phone number, your social, when you ain’t done nothing. Just so they know everybody in the hood.” . . The consequences could be severe. The information of civilians stopped in the intersection would be fed into the data system, even if they hadn’t committed any offenses.

PredPol’s earthquake theory of crime

In addition to running Operation Laser, LAPD contracted with PredPol, a company that grew out of a research project between LAPD and the UCLA professor Jeff Brantingham.

PredPol applied an earthquake prediction model to crime. The underlying theory – which the company once compared to the unproven and controversial broken windows policing strategy– was that like earthquakes and their aftershocks, smaller crimes were gateways to bigger crimes and occurred in similar places.While the mathematics might look complicated for “normal mortal humans”, PredPol said in a 2014 presentation obtained by Motherboard, the model was “based on nearly seven years of detailed academic research into the causes of crime pattern formation”.

But academics say the theory is flawed, and the math the company pitched to police was too simple to effectively predict crime. The model was essentially assessing where arrests had been made and sending police back to those locations, according to those academics.

More than a dozen police departments experimented with PredPol, including in Palo Alto and Mountain View. But by the end of 2019, both Operation Laser and PredPol had garnered intense criticism, with skeptics charging that the systems perpetuated discrimination.

By that time, several police departments had dropped their contracts with PredPol, saying there was little proof it helped reduce crime. After three years of use, the Palo Alto police department “didn’t get any value out of it”, a spokesperson, Janine De la Vega, said at the time.

LAPD initially promised reform, but ultimately shuttered Operation Laser in April 2019 and canceled its contract with PredPol in April 2020. LAPD conceded the data used in Operation Laser “was inconsistent” and needed to be reassessed. PredPol, it said, was terminated because of budgetary constraints due to the pandemic. Still, the police chief, Michel Moore, maintained the underlying principles of the program were valuable.

A bid to establish ‘digital trust’

With the data-driven programs the LAPD had promoted for years gone, a new effort took their place. Days before announcing the end of PredPol, LAPD published information about what it called data-informed community-focused policing. The intention of DICFP, the department said, was to establish a deeper relationship between community members and police and address some of the concerns the public had with previous policing programs, all while working to prevent crime. “The legitimacy of a police department is dependent on a community’s trust in its police officers,” an April 2020 LAPD brochure on the program read.

[. . .]

The similarities start with what LAPD now calls “neighborhood engagement areas” or “neighborhoods experiencing crimes and low community engagement”. Like anchor points, those areas are identified based on information such as crime data and calls for service, which include anything from calls about robberies to traffic-related incidents and “non-emergency” calls, according to a daily operations guide.

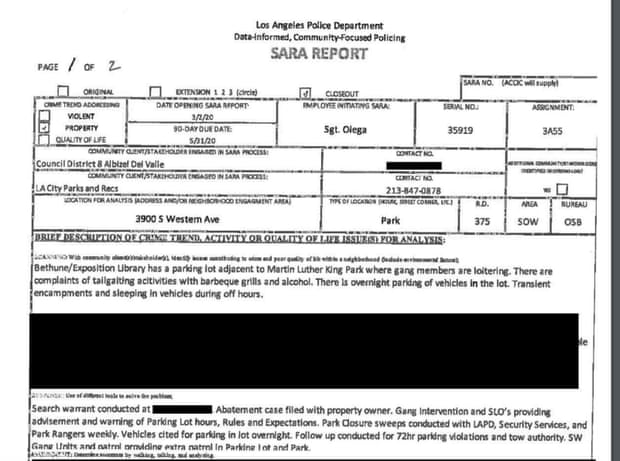

To address crime in neighborhood engagement areas, according to the brochure, LAPD would use a problem-solving model first introduced under Operation Laser called Sara – an acronym for scanning, analysis, response and assessment. As part of that model, police and stakeholders would use tools such as increased patrolling and surveillance to prevent future crimes.

Similar in process to Operation Laser, DICFP would lead to similar results: at least one anchor point under the previous regime was also selected as a neighborhood engagement area in 2020 and at least one other area of interest was located within what was previously a Laser zone, the documents show.

[. . ]

“I don’t know about you but I’m not building trust with someone who spies on me,” said Tracey Corder, the deputy campaign director at Acre, a group that helps local organizations campaign against racial injustice.

“It sounds like a rebrand,” she continued. “It’s a co-option of organizer demands and organizing wins. We have set the stage and said policing as it exists does not work. All of this has been an effort to not actually change, but rebrand and reuse what they’ve already been doing.”

Cahn, the Surveillance Technology Oversight Project founder, said: “It seems like the worst sort of fear of organizers. Rather than actually addressing any of the substantive harms that come from predictive policing, they’re simply providing this veneer of community engagement.”

LAPD did not reply to repeated and detailed requests for comment.

‘They’re trying to do some whitewashing’

The LAPD was not alone in rebranding its predictive policing efforts. A month after the department introduced DICFP, PredPol changed its name to Geolitica. On the company website, where there was once a banner that said it was “the predictive policing company” that works to “predict critical events”, Geolitica now boasts “data-driven community policing” that helped public safety teams “be more transparent, accountable, and effective.”

Privacy advocates say LAPD and PredPol’s efforts were part of a larger trend in the predictive policing industry – both in police departments and private companies. In response to public criticism of predictive policing, companies have rebranded existing products or launched new products that promote police accountability and transparency.

“They’re definitely aware of all the negative connotations of predictive policing,” said Brian Hofer, the executive director of the government reform advocacy group Secure Justice and the chair of the Oakland Privacy Commission. “They’re trying to really do some whitewashing by rebranding different verbiage and talking about serving these communities instead.”

But safeguards shouldn’t be left to police or tech companies to implement, Corder argues.

“When you think about the way police respond to any kind of calls for reforms from civilians, it’s always oppositional,” Corder said of police departments that use these purported accountability services. “But now all of a sudden we’re supposed to believe they are fine with oversight coming from tech companies? Anybody should be concerned about that and we should start asking the question of why.”

Sam Levin contributed reporting

Badly Wanted by The FBI: Paid Informants...Just Say No and There is No Right-to-Hassle-Free Travel

from the hard-to-prove-anything-that-can't-be-confirmed-or-denied dept

• an inability to print a boarding pass at home, requiring him to interact with ticketing agents “for an average of at least one hour, when government officials often appear and question” him;

• an SSSS designation on his boarding passes;

• TSA searches of his belongings, “with the searches usually lasting at least an hour”;

• TSA pat downs when departing the U.S. and CBP pat downs when returning to the U.S.;

• encounters with federal officers when boarding and deboarding planes;

• questioning and searches by CBP officers “for an average of two to three hours” after returning from international travel;

• CBP confiscation of his laptop and cellphone “for up to three weeks”;

• being taken off an airplane two times after boarding; and

• being detained for seven hours by DHS and CBP officials in Buffalo, New York in May 2012 and being detained in Dubai for two hours in March 2019.

Ghedi approached the DHS through its court-mandated redress program to inquire about his status twice -- once in 2012 and again in 2019.

Ghedi approached the DHS through its court-mandated redress program to inquire about his status twice -- once in 2012 and again in 2019. Ghedi brings two Fourth Amendment claims. The first alleges that the heads of the DHS, TSA, and CBP violated his Fourth Amendment rights through “prolonged detentions,” and “numerous invasive, warrantless patdown searches” lacking probable cause. The second alleges that the heads of the DHS, TSA, and CBP also violated his Fourth Amendment rights through their agents conducting “warrantless searches of his cell phones without probable cause.” The Fourth Amendment protects “[t]he right of the people to be secure in their persons . . . and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures.”

The district court said he had no standing to sue.

The Fifth Circuit says he does. But standing to sue doesn't matter if you sue the wrong people. The Appeals Court says there's a plausible injury alleged here, but it wasn't perpetrated by the named defendants.

[. . .] There are some rights the court will recognize but this isn't one of them.

In short, Ghedi has no right to hassle-free travel. In the Supreme Court’s view, international travel is a “freedom” subject to “reasonable governmental regulation.” And when it comes to reasonable governmental regulation, our sister circuits have held that Government-caused inconveniences during international travel do not deprive a traveler’s right to travel.

And, putting the final nail in Ghedi's litigation coffin, the Appeals Court says the government's secrets may harm individuals but they can't harm their reputation… because they're secret.

As we noted at the outset, Ghedi’s status on the Selectee List is a Government secret. Simply put, secrets are not stigmas. The very harm that a stigma inflicts comes from its public nature. Ghedi pleaded no facts to support that the Government has ever published his status—one way or the other—on the Selectee List. His assertions that the Government has attached the “stigmatizing label of ‘suspected terrorist’” and “harm[ed] . . . his reputation” are legal conclusions, not factual allegations.

That's how it goes for litigants trying to sue over rights violations perpetrated by agencies engaged in the business of national security. Allegations are tough to verify because the government refuses to confirm, deny, or even discuss a great deal of its national security work in court. Ghedi could always try this lawsuit again, perhaps armed with FOIA'ed documents pertaining to his travels and the many agencies that make it difficult for him. But that's as unlikely to result in clarifying information for the same reason: national security.

Heads, the government wins. Tails, the plaintiff loses.

Ghedi is still free to pursue lawsuits against the individual agents who hassled him, took his stuff, and tried to coerce him into becoming an informant, but given the national security implications and the ongoing existence of qualified immunity, it's just as likely he'd lose that suit as well."

Filed Under: 5th circuit, abdulaziz ghedi, civil rights, dhs, doj, fbi, informants, somalia

-

Flash News: Ukraine Intercepts Russian Kh-59 Cruise Missile Using US VAMPIRE Air Defense System Mounted on Boat. Ukrainian forces have made ...