At this point, it has become cliché to say that nothing in 2022 turned out the way we expected. We left the COVID-19 crisis behind hoping for a long-awaited return to normality and were immediately plunged into the chaos and uncertainty of a twentieth-century-style military conflict that posed serious risks of spreading over the continent. While the broader geopolitical analysis of the war in Ukraine and its consequences are best left to experts, a number of cyberevents have taken place during the conflict, and our assessment is that they are very significant.

In this report, we propose to go over the various activities that were observed in cyberspace in relation to the conflict in Ukraine, understand their meaning in the context of the current conflict, and study their impact on the cybersecurity field as a whole.

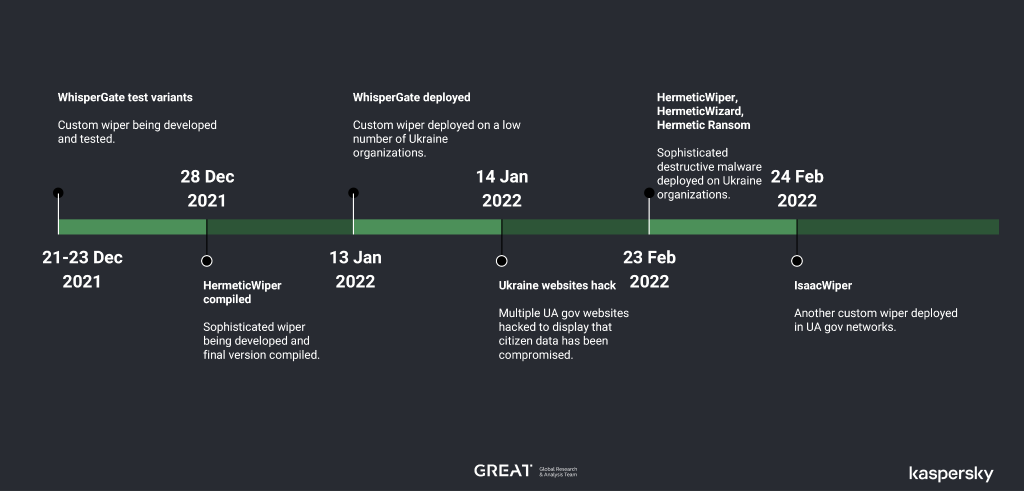

Timeline of significant cyber-events predating Feb 24th

In the modern world, it has become very difficult to launch any kind of military campaign without intelligence support in the field. Most intelligence is gathered from various sources through methods such as HUMINT (human intelligence, gathered from persons located in the future conflict area), SIGINT (signals intelligence, gathered through the interception of signals), GEOINT (geospatial intelligence, such as maps from satellites), or ELINT (electronic intelligence, excluding text or voice), and so on.

For instance, according to the New York Times, in 2003, the United States made plans for a huge cyberattack to freeze billions of dollars in Saddam Hussein’s bank accounts and cripple his government before the invasion of Iraq. However, the plan was not approved because the government feared collateral damage. Instead, a more limited plan to cripple Iraq’s military and government communication systems was carried out during the early hours of the war in 2003. This operation included blowing up cellphone towers and communication grids as well as jamming and cyberattacks against Iraq’s telephone networks. According to the same article, another such attack took place in the late 1990s when the American military attacked a Serbian telecommunications network. Inadvertently, this also affected the Intelsat communications system for days, proving that the risk of collateral damage during cyberwarfare is pretty high.

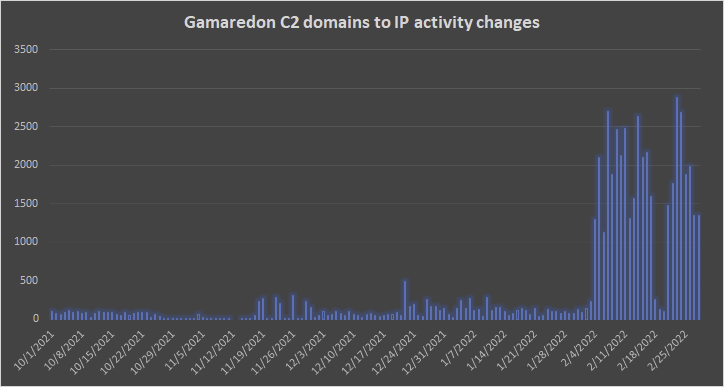

The lessons learned from these events may allow predicting kinetic conflicts by monitoring new cyberattacks in potential areas of conflict. For instance, in late 2013 and January 2014, we observed higher-than-normal activity in Ukraine by the Turla APT group, as well as a spike in the number of BlackEnergy APT sightings. Similarly, at the beginning of February 2022, we noticed a huge spike in the amount of activity related to Gamaredon C&C servers. This activity reached hitherto-unseen levels, suggesting massive preparations for a major SIGINT gathering effort.

As shown by these cases, during modern conflicts, we can expect to see significant signs and spikes in cyberwarfare relating to both collection of intelligence and destructive attacks in the days and weeks preceding military attacks. Of course, we should note that the opposite is also possible: for instance, starting in June 2016, but most notably since September 2016 all the way to December 2016, the Turla group intensified their satellite-based C&C registrations tenfold compared to its 2015 average. This indicated unusually high activity by the Turla group, which signaled a never-before-seen mobilization of the group’s resources. At the same time, there was no ensuing military conflict that we know of.

Key insights

- Today’s military campaigns follow gathering of supporting intelligence in the field; this includes SIGINT and ELINT among others

- Significant military campaigns, such as the 2003 invasion of Iraq, have been complemented by powerful cyberattacks designed to disable the enemy’s communication networks

- In February 2022, we noticed a huge spike in activity related to Gamaredon C&C servers; a similar spike was observed in Turla and BlackEnergy APT activity in late 2013 and early 2014

- We can expect to see significant signs and spikes in cyberwarfare in the days and weeks preceding military conflicts

Day one

On the very first day of the conflict (February 24, 2022), a massive wave of indiscriminate pseudo-ransomware and wiper attacks hit Ukrainian entities. We were not able to determine any form of consistency when it came to the targeting, which led us to believe that the main objective of these attacks may have been to cause chaos and confusion — as opposed to achieving precise tactical goals. Conversely, the tools leveraged in this phase were just as varied in nature:

- Ransomware (IsaacRansom);

- Fake ransomware (WhisperGate);

- Wipers (HermeticWiper, CaddyWiper, DoubleZero, IsaacWiper);

- ICS/OT wipers (AcidRain, Industroyer2).

Some of them were particularly sophisticated. As far as we know, HermeticWiper remains the most advanced wiper software discovered in the wild. Industroyer2 was discovered in the network of a Ukrainian energy provider, and it is very unlikely that the attacker would have been able to develop it without access to the same ICS equipment as used by the victim. That said, a number of those tools are very crude from a software engineering perspective and appear to have been developed hurriedly.

With the notable exception of AcidRain (see below), we believe that these various destructive attacks were both random and uncoordinated – and, we argue, of limited impact in the grand scheme of the war. Our assessment of the threat landscape in Ukraine in the first months of the war can be found on SecureList.

The volume of wiper and ransomware attacks quickly subsided after the initial wave, but a limited number of notable incidents were still reported. The Prestige ransomware affected companies in the transportation and logistics industries in Ukraine and Poland last October. One month later, a new strain named RansomBoggs again hit Ukrainian targets – both malware families were attributed to Sandworm. Other “ideologically motivated” groups involved in the original wave of attacks appear to be inactive now.

Key insights

- Low-level destructive capabilities can be bootstrapped in a matter of days.

- Based on the uncoordinated nature of these destructive attacks, we assess that some threat actors appear to be capable of recruiting isolated groups of hackers on short notice, to perform destabilizing tasks. We can only speculate as to whether those groups are internal resources reassigned to low-level cyberattacks or external entities that can be mobilized when the need arises.

- While the impact of these destructive cyber-attacks paled in comparison to the effects of the kinetic attacks taking place at the same time, it should be noted that this capability could in theory be directed against any country outside of the context of an armed conflict and under the pretense of traditional cybercrime activity.

The Viasat “cyberevent”

On the 24th of February, Europeans who relied on the ViaSat-owned “KA-SAT” satellite faced major Internet access disruptions. This so-called “cyber-event” started around 4h UTC, less than two hours after the Russian Federation publicly announced the beginning of the “special military operation” in Ukraine. As could be read from government requests for proposals, the Ukrainian government and military are notable consumers of KA-SAT access, and were reportedly affected by the event. But the disruptions also triggered major consequences elsewhere, such as interrupting the operation of wind turbines in Germany.

ViaSat quickly suspected that disruptions could be the result of a cyberattack. It directly affected satellite modems firmwares, but was still to be understood as of mid-March. Kaspersky experts ran their own investigations and notably uncovered a likely intrusion path to a remote access point in a management network, while analyzing modem internals and a likely-involved wiper implant. The “AcidRain” wiper was first described later in March, while ViaSat published an official analysis of the cyber-attack. The latter confirmed that a threat actor got in through a remote-management network exploiting a poorly configured VPN, and ultimately delivered destructive payloads, affecting tens of thousands of KA-SAT modems. On May 10, the European Union attributed those malicious activities to the Russian Federation.

A lot of technical details about this attack are still unknown and may later be shared away from government eyes. Yet it is one of the most sophisticated attacks revealed to date in connection to the conflict in Ukraine. The malicious activities were likely conducted by a skilled and well-prepared threat actor, within an accurate timeframe which cannot be fortuitous. While the sabotage has likely failed to disrupt the Ukrainian defense badly enough, it had multiple effects beyond the battlefield: stimulating the US Senate to require a state of play on satellite cybersecurity, accelerating SpaceX Starlink deployment (and later, unexpected bills), as well as questioning the rules for dual-use infrastructure during armed conflicts.

Key insights

- The ViaSat sabotage once again demonstrates that cyberattacks are a basic building block for modern armed conflicts and may directly support key milestones in military operations.

- As it has been suspected for years, advanced threat actors likely preposition themselves in various strategic infrastructural assets in preparation for future disruptive actions.

- Cyberattacks against common communication infrastructures are highly likely during armed conflict, as belligerents might consider these to be of dual use. Due to the interlinked nature of the Internet, a cyberattack against this kind of infrastructure will likely have side-effects for parties that are not involved in the armed conflict. Protection and continuity planning are of utmost importance for this communications infrastructure.

- The cyberattack raises concerns about the cybersecurity of commercial satellite systems, which may support various applications, from selfie geolocation to military communications. While protective measures against kinetic combat in space are frequently discussed by military forces, and more datacenters are expecting to fly soon … ground-station management systems and operators still seem to be highly exposed to common cyberthreats.

Taking sides: professional ransomware groups, hacktivists, and DDoS attacks

As has always been the case, wartime has a very specific impact on the information landscape. It is especially true in 2022, now that humanity commands the most potent information spreading tools ever created: social networks and their well-documented amplification effect. Most real-world events related to the war (accounts of skirmishes, death tolls, prisoner of war testimonies) are shared and refuted online with varying degrees of good faith. Traditional news outlets are also affected by the broader context of information warfare.

DDoS attacks and, to a lesser extent, defacement of random websites have always been regarded as low-sophistication and low-impact attacks by the security community. DDoS attacks, in particular, require generating heavy network traffic that attackers typically cannot sustain for very long periods of time. As soon as the attack stops, the target website becomes available again. Barring temporary loss of revenue for e-commerce websites, the only value provided by DDoS attacks or defacement is the humiliation of the victim. Since non-specialized journalists may not know the difference between the various types of security incidents, their subsequent reporting shapes a perception of incompetence and inadequate security that may erode users’ confidence. The asymmetric nature of cyberattacks plays a key role in supporting a David vs. Goliath imagery, whereby symbolic wins in the cyberfield help convince ground troops that similar achievements are attainable on the real-life battlefield.

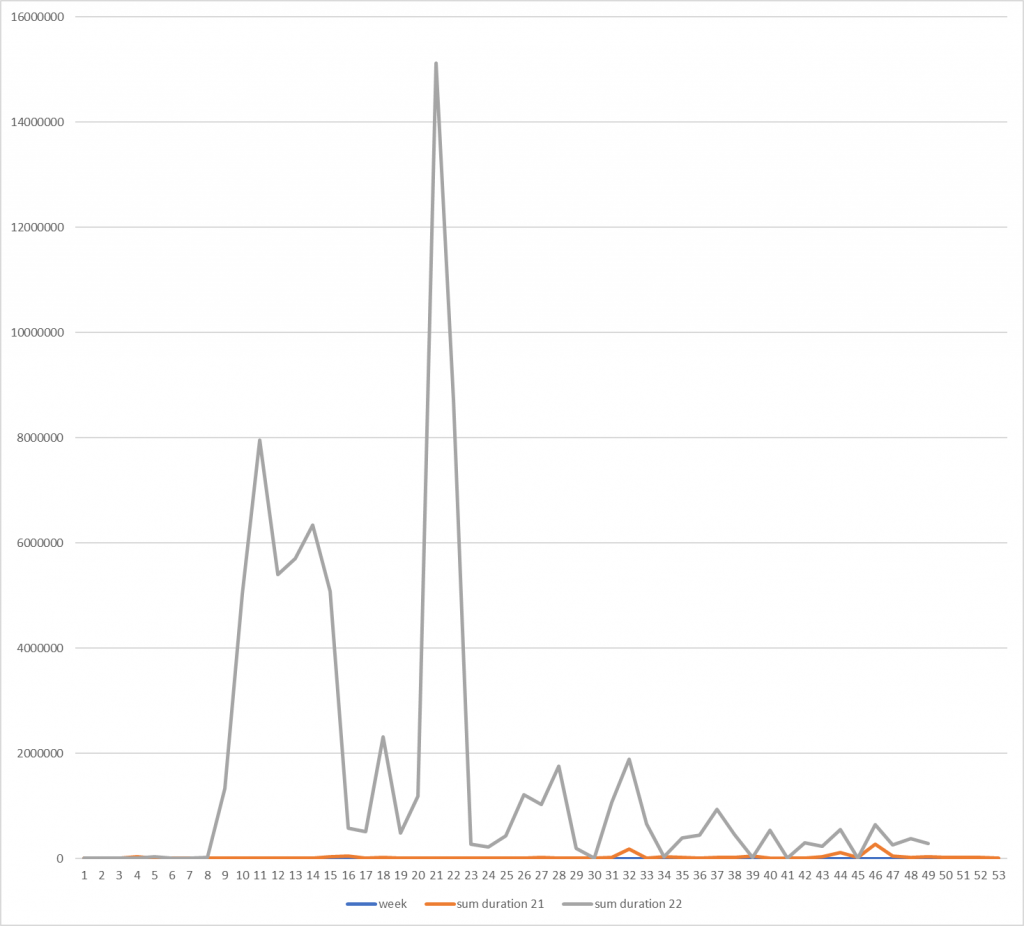

According to Kaspersky DDoS Protection, since the beginning of 2022 during 11 months the service registered ~1.65 more attacks than in the whole 2021. While this growth may be not too significant, the resources have been under attack 64 times longer compared to 2021. In 2021 the average attack lasted ~28 minutes, in 2022 – 18.5 hours, which is almost 40 times longer. The longest attack lasted 2 days in 2021, 28 days (or 2486505 seconds) in 2022.

Total duration of DDoS attacks detected by Kaspersky DDoS Protection in seconds, by week, 2021 vs 2022

Since the start of the war, a number of (self-identified) hacktivist groups have emerged and started conducting activities to support either side. For instance, a stunt organized by the infamous collective Anonymous involved causing a traffic jam in Moscow by sending dozens of taxis to the same location.

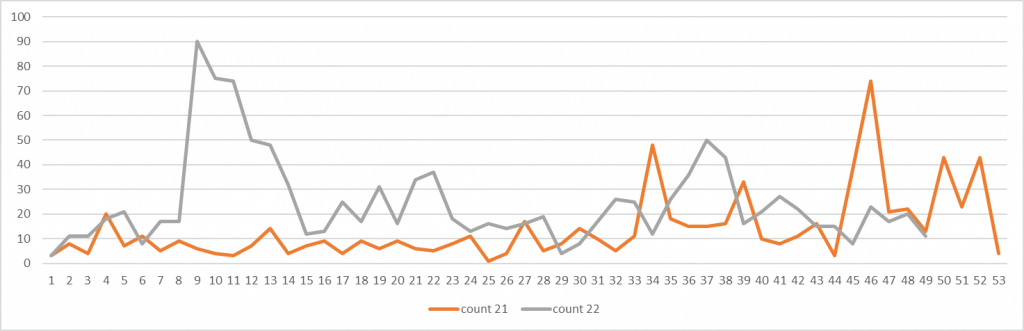

Kaspersky DDoS protection also reflects this trend. Massive DDoS attacks were spread unevenly over the year with the most heated times being in spring and early summer.

Number of DDoS attacks detected by Kaspersky DDoS Protection in seconds, by week, 2021 vs 2022

The attackers peaked in February-early March, reflecting growth of hacktivism, which has died down by autumn. Currently we see a regular anticipated dynamic of attacks, though their quality has changed. In May-June we detected extremely long attacks. Now their length has stabilized, nevertheless, while typical attacks used to last a few minutes, now they last for hours.

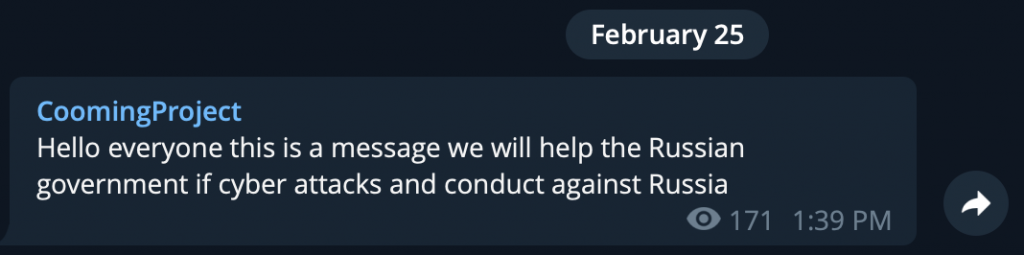

On February 25, 2022, the infamous Conti ransomware group announced their “full support of Russian government”. The statement included a bold phrase: “If anybody will decide to organize a cyberattack or any war activities against Russia, we are going to use our all possible resources to strike back at the critical infrastructures of an enemy“. The group followed up rather quickly with another post, clarifying their position in the conflict: “As a response to Western warmongering and American threats to use cyber warfare against the citizens of Russian Federation, the Conti Team is officially announcing that we will use our full capacity to deliver retaliatory measures in case the Western warmongers attempt to target critical infrastructure in Russia or any Russian-speaking region of the world. We do not ally with any government and we condemn the ongoing war. However, since the West is known to wage its wars primarily by targeting civilians, we will use our resources in order to strike back if the well being and safety of peaceful citizens will be at stake due to American cyber aggression“.

Two days later, a Ukrainian security researcher leaked a large batch of internal private messages between Conti group members, covering over one year of activity starting in January 2021. This dump delivered a significant blow to the group who saw their inner activities exposed before the public, including Bitcoin wallet addresses related to many million of US dollars received in ransom. At the same time, another cybercriminal group called “CoomingProject” and specializing in data leaks, announced they would support the Russian Government if they saw attacks against Russia:

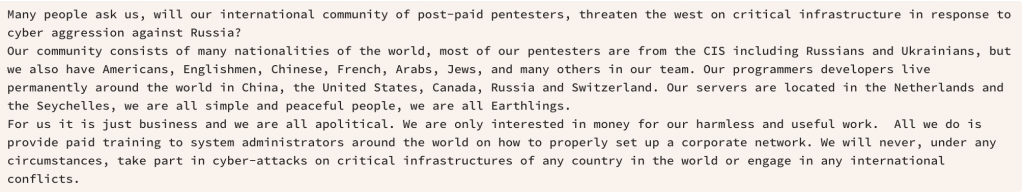

Other groups, such as Lockbit, preferred to stay neutral, claiming their “pentesters” were an international community, including Russians and Ukrainians, and it was “all business”, in a very apolitical manner:

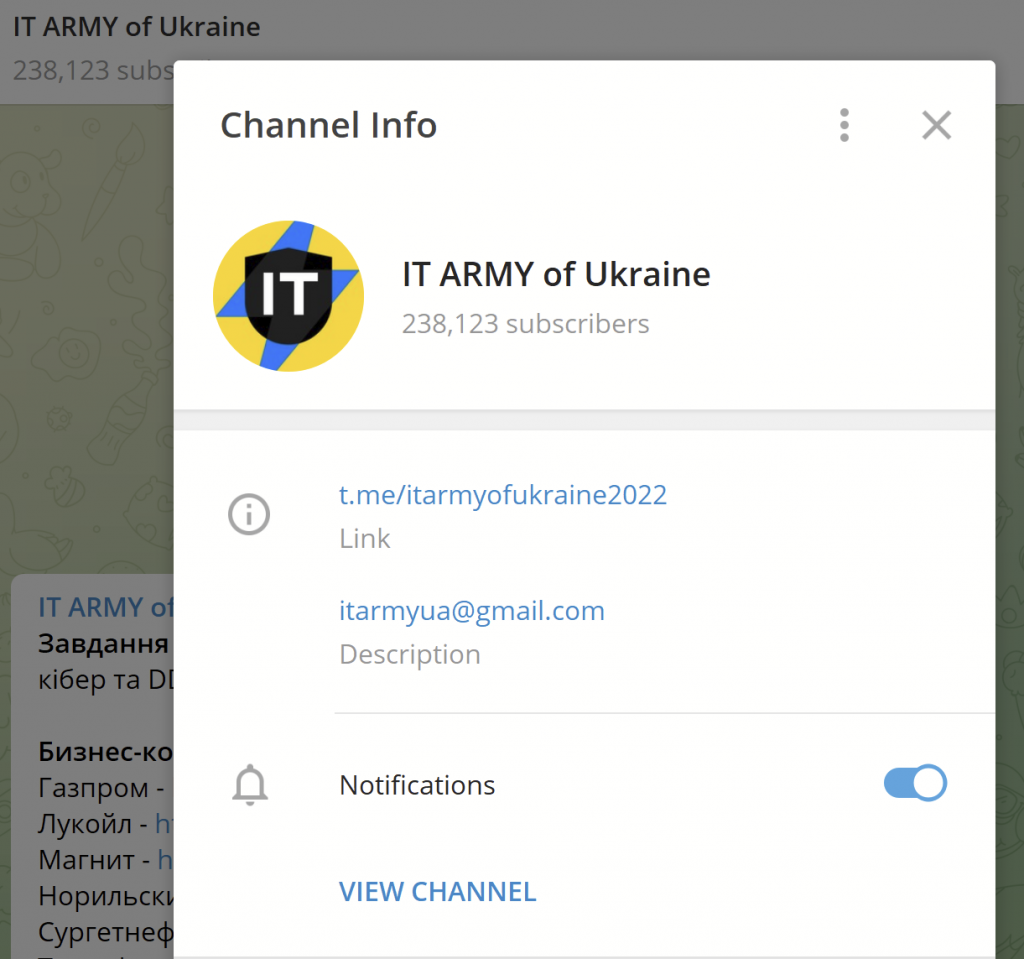

On February 26, Mykhailo Fedorov, the Vice Prime Minister and Minister of Digital Transformation of Ukraine, announced the creation of a Telegram channel to “continue the fight on the cyber front”. The initial Telegram channel had a typo in the name (itarmyofurraine) so a second one was created.

IT ARMY of Ukraine Telegram channel

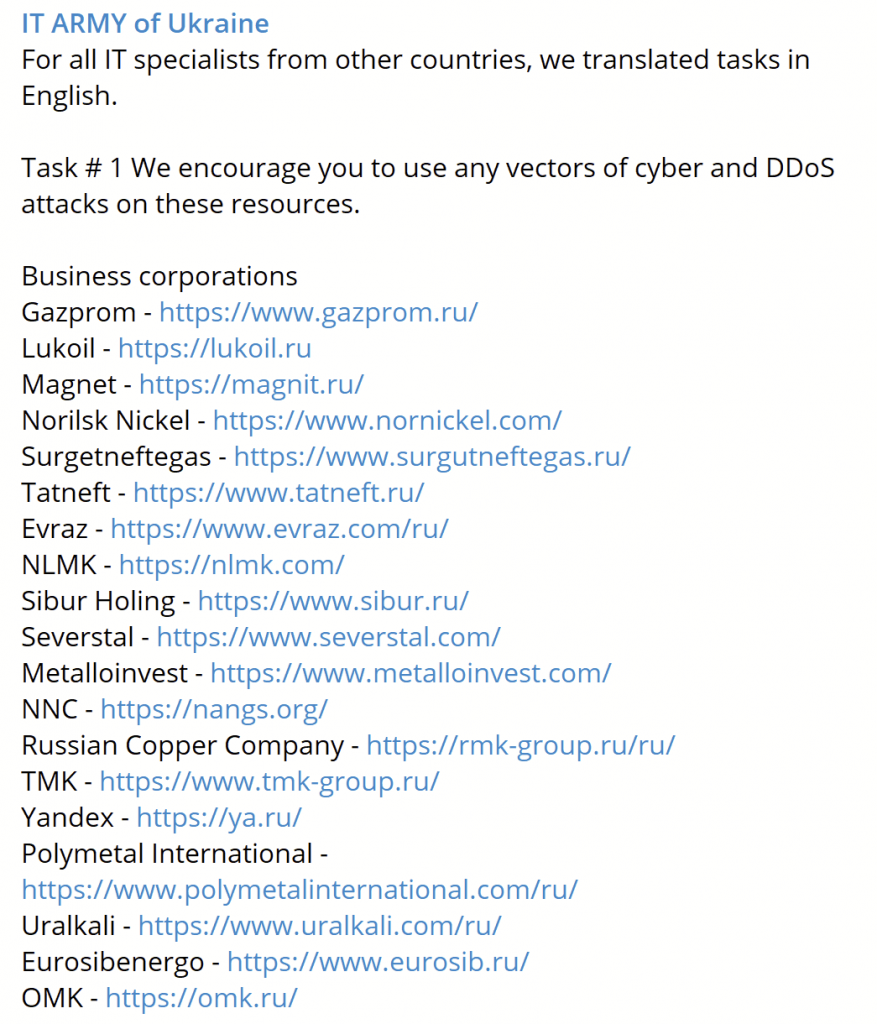

The channel operators constantly give tasks to the subscribers, such as DDoS’ing various business corporations, banks, or government websites:

List of DDoS targets posted by IT ARMY of Ukraine

Within a short time, the IT Army of Ukraine, composed of volunteers coordinating via Twitter and Telegram, reportedly defaced or otherwise DDoSed over 800 websites, including high-profile entities such, as the Moscow Stock Exchange[1].

Parallel activity has also been observed by other groups, which have taken sides as the conflict was spilling over into neighboring countries. For instance, the Belarusian Cyber-Partisans claimed they had disrupted the operations of the Belarusian Railway by switching it to manual control. There goal was to slow the movement of Russian military forces through the country.

Belarusian Cyber-Partisans post

A limited and by far not exhaustive list of some of the ransomware or hacktivist groups that expressed their opinion about the conflict in Ukraine include:

| Open UA support | Open RU support | Neutral |

| RaidForums | Conti ransomware | Lockbit ransomware |

| Anonymous collective | CoomingProject ransomware | ALPHV ransomware |

| IT ARMY of Ukraine | Stormous ransomware | |

| Belarusian Cyber-Partisans | KILLNET | |

| AgainstTheWest | ||

| NB65 | ||

| Squad303 | ||

| Kelvinsecurity + … |

Among the openly pro-Russian groups, Killnet, which was originally established as a response to the “IT Army of Ukraine”, is probably the most active. In late April, they attacked Romanian Government websites in response to statements by Marcel Ciolacu, president of the Romanian Chamber of Deputies, after he promised Ukrainian authorities “maximum assistance”. On May 15, Killnet published a video on their telegram channel declaring war on ten nations: the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, Italy, Latvia, Romania, Lithuania, Estonia, Poland, and Ukraine. Following these activities, the international hacking collective known as “Anonymous” declared cyber war against Killnet on May 23.

Killnet continued its activities throughout 2022, preceding their attacks with an announcement on their Telegram channel. In October, the group started attacking organizations in Japan, which they later stopped due to a lack of funds. It later attacked a US airport and governmental websites and businesses, often without significant success. On November 23, Killnet briefly took down the website of the European Union. Killnet also repeatedly targeted websites in Latvia, Lithuania, Norway, Italy, and Estonia. While Killnet’s methods are not sophisticated, they continually make headlines and drive attention to the group’s activities and stance.

Key insights

- The conflict in Ukraine has created a breeding ground for new cyberware activity by various parties including cybercriminals and hacktivists, who rushed to support their favorite sides

- We can expect the involvement of hacktivist groups in all major geopolitical conflicts from now on.

- The cyberware activities are spilling over into neighboring countries and affecting a large number of entities, including governmental institutions and private companies

- Some groups, such as the IT Army of Ukraine, have been officially backed by governments, and their Telegram channels include hundreds of thousands of subscribers

- The majority of attacks have relatively low complexity

- Most of the time, attacks conducted by these groups have a very limited impact on operations but may erroneously be reported as serious incidents and cause reputational damage.

- These activities may originate from genuine “grassroots” hacktivists, groups encouraged or supported by one of the belligerents, or from the belligerents themselves – and telling which is which may well prove impossible.

Hack and leak

On the more sophisticated end of attacks attempting to hijack media attention, hack-and-leak operations have been on the rise since the beginning of the conflict. The concept is simple: breaching into an organization and publishing its internal data online, often via a dedicated website. This is significantly more difficult than a simple defacing operation, since not all machines contain internal data worth releasing. Hack-and-leak operations, therefore, require more precise targeting, and will, in most cases, also demand more skill from attackers, as the information they are looking for is, more often than not, buried deep within in the victim’s network.

An example of such a campaign is the “doxing” of Ukrainian soldiers. Western entities were also targeted, such as the Polish government or many prominent pro-Brexit figures in the UK. In the latter cases, internal emails were published, leading to scrutiny by investigative journalists. In theory, these data leaks are subject to manipulation. The attackers have all the time they need to edit any released document or could just as well inject entirely forged ones.

It is important to note that it is absolutely unnecessary for the attacker to go to such lengths for the data leak to be damaging. The public availability of the data is proof itself that a serious security incident took place, and the legitimate, original content may already contain incriminating information.

Key insights

- In our 2023 APT predictions, we foresee that hack-and-leak operations will be on the rise next year, as they are very efficient against entities that already have high media exposure and corruption levels (i.e. politicians).

- Information warfare is not internal to a conflict, but instead directed at all onlookers. We expect that the vast majority of such attacks will not be directed at the belligerents, but rather at entities who are perceived as being too supportive (or not supportive enough) of either side.

- Whether it is hack-and-leak operations or DDoS, cyberattacks emerge as a non-kinetic means of diplomatic signaling between states.

Poisoned open-source repositories, weaponizing open-source software

Open-source software has many benefits. Firstly, it is often free to use, which means that businesses and individuals can save money on software costs. However, since anyone can contribute to the code and make improvements, this can also be abused and in turn, open security trapdoors. On the other hand, since the code can be publicly examined for any potential security vulnerabilities, it also means that given enough scrutiny, the risks of using open-source software can be mitigated to decent levels.

Back in March, RIAEvangelist, the developer behind the popular npm package “node-ipc”, published modified versions of the software that contained a special functionality if the running systems had a Russian or Belarusian IP address. On such systems, the code would overwrite all files with a heart emoji, additionally deploying the message, WITH-LOVE-FROM-AMERICA.txt, originating in another module created by the same developer. The node-ipc package is quite popular with over 800,000 users worldwide. As is often the case with open-source software, the effect of deploying these modified “node-ipc” versions was not restricted to direct users; other open-source packages, for instance “Vue.js”, which automatically include the latest node-ipc version, amplified the effect.

Packages aimed to be spread in the Russian market did not always lead to destruction of files, some of them contained hidden functionality such as adding a Ukrainian flag to a section of the website of software or political statements in support of the country. In certain cases the functionality of the package is removed and replaced with political notifications. It is worth noting that not all packages had this functionality hidden with some authors announcing the functionality in the package description.

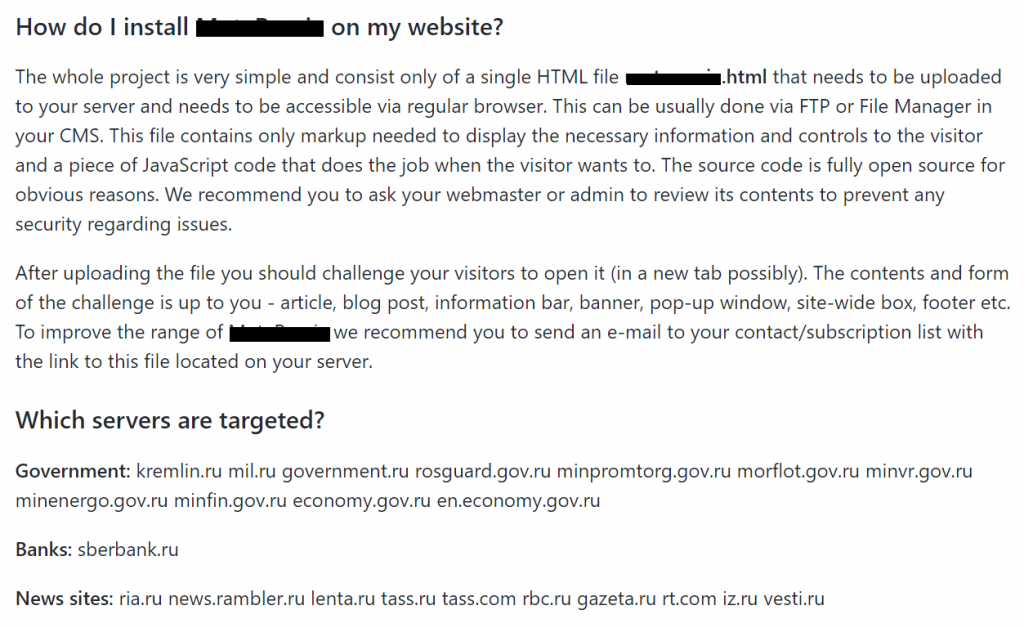

One of the projects encourages to spread a file that once opened will start hitting various pages of the enlisted servers via JavaScript to overload the websites

Other repositories and software modules found on GitHub included those specifically created to DDoS Russian governmental, banking and media sites, network scanners specifically for gathering data about Russian infrastructure and activity and bots aimed at mass reporting of Telegram channels.

Key insights

- As the conflict drags on, popular open-source packages can be used as a protest or attack platform by developers or hackers alike

- The impact from such attacks can extend further that the open-source software itself, propagating to other packages that automatically rely on the trojanized code

Fragmentation

During the past years, most notably after 2014, this process began to expand to the IT Security world, with nation states passing laws banning each other’s products, services, and companies.

Following the start of the conflict in Ukraine in February 2022, we have seen a lot of western companies exiting the Russian market and leaving their users in a difficult position when it comes to receiving security updates or support. At the same time, some western nations have pushed laws banning the use of Russian software and services due to a potential risk of these being used to launch attacks.

Obviously, one cannot totally rule out the possibility of political pressure being applied to weaponize products, technologies, and services of some minor market players. When it comes to global market leaders and respected vendors, however, we believe this to be extremely unlikely.

On the other hand, searching for alternative solutions can be extremely complicated. Products from local vendors, whose secure development culture, as we have often found, is usually significantly inferior to that of global leaders, are likely to have “silly” security errors and zero-day vulnerabilities, rendering them easy prey for both cybercriminals and hacktivists.

Should the conflict continue to exacerbate, organizations based in countries where the political situation does not require addressing the above issues, should still consider the future risk factors that may affect everyone:

- The quality of threat detection decreases as IS developers lose some markets, resulting in the expected loss of some of their qualified IS experts. This is a real risk factor for all security vendors experiencing political pressure.

- The communication breakdowns between IS developers and researchers located on opposite sides of the new “iron curtain” or even on the same side (due to increased competition on local markets) will undoubtedly decrease the detection rates of security solutions that are currently being developed.

- Decreasing CTI quality: unfounded politically motivated cyberthreat attribution, exaggerated threats, lower statement validity criteria due to political pressure and in an attempt to utilize the government’s political narrative to earn additional profits.

Government attempts to consolidate information about incidents, threats, and vulnerabilities and to limit access to this information detract from overall awareness, since information may sometimes be kept under wraps without good reason.

Key insights

- Geopolitics are playing an important role and the process of fragmentation is likely going to expand

- Security updates are probably the top issue when vendors end support for products or leave the market

- Replacing established, global leaders with local products might open the doors to cybercriminals exploiting zero-day vulnerabilities

Did a cyberwar happen?

Ever since the beginning of the conflict, the cybersecurity community has debated whether or not what was going on in Ukraine qualifies as “cyberwar”. One indisputable fact, as documented throughout this report, is that significant cyberactivity did take place in conjunction with the start of the conflict in Ukraine. This may be the only criteria we need.

On the other hand, many observers had envisioned that in the case of a conflict, devastating preemptive cyberattacks would cripple the “special operation” party. With the notable exception of the Viasat incident, whose actual impact remains hard to evaluate, this simply did not take place. The conflict instead revealed an absence of coordination between cyber- and kinetic forces, and in many ways downgraded cyberoffense to a subordinate role. Ransomware attacks observed in the first weeks of the conflict qualify as distractions at best. Later, when the conflict escalated this November and the Ukrainian infrastructure (energy networks in particular) got explicitly targeted, it is very telling that the Russian military’s tool of choice for the job was missiles, not wipers[2].

If you subscribe to the definition of cyberwar as any kinetic conflict supported through cyber-means, regardless of their tactical or strategic value, then a cyberwar did happen in February 2022. Otherwise, you may be more satisfied with Ciaran Martin‘s qualification of “cyberharassment”[3].

Key insights

- There is a fundamental impracticality to cyberattacks; an impracticality that can only be justified when stealth matters. When it does not, physical destruction of computers appears to be easier, cheaper, and more reliable.

- Unless very significant cyberattacks have failed to reach public awareness, at the time of writing this, the relevance of cyberattacks in the context of open war has been vastly overestimated by our community.

Conclusion

The conflict in Ukraine will have a lasting effect on the cybersecurity industry and landscape as a whole. Whether the term “cyberwar” applies or not, there is no denying that the conflict will forever change everyone’s expectations about cyberactivity conducted in wartime, when a major power is involved. Unfortunately, there is a chance that established practice will become the de facto norm.

Before the war broke out, several ongoing multiparty processes (UN’s OEWG and GGE) attempted to establish a consensus on acceptable and responsible behavior in cyberspace. Given the extreme geopolitical tensions we are currently experiencing, it is doubtful that these already difficult discussions will bear fruit in the near future.

A promising initiative in the meantime is the ICRC’s “digital emblem” project: a proposed solution to clearly identify machines used for medical or humanitarian purposes, in the hopes that attackers will refrain from damaging them. Just like the real-life red cross and red crescent emblems cannot stop bullets, digital emblems will not prevent cyberattacks on a technical level – but they will at least make it obvious to everyone that medical infrastructure is not a legitimate target.

As it seems more and more likely that the conflict will drag on for years, and with the death toll already being high… we hope that everyone can at least agree on that.

[1] The point of this section is not to evaluate the accuracy of those numbers, which are self-reported in many cases, but to study how these cyberattacks are used to shape narratives.

[2] This report does not make the assumption that the Russian military would use, could use, or has ever used wiper malware. US-CERT however went on the record on this exact subject. So did a number of industry peers.

[3] We recognize that information about ongoing cyberattacks and their impact isn’t exactly forthcoming. This assessment may be revised at a later date, when more data becomes available.