Don’t Stop Thinking About (Tom) Tomorrow

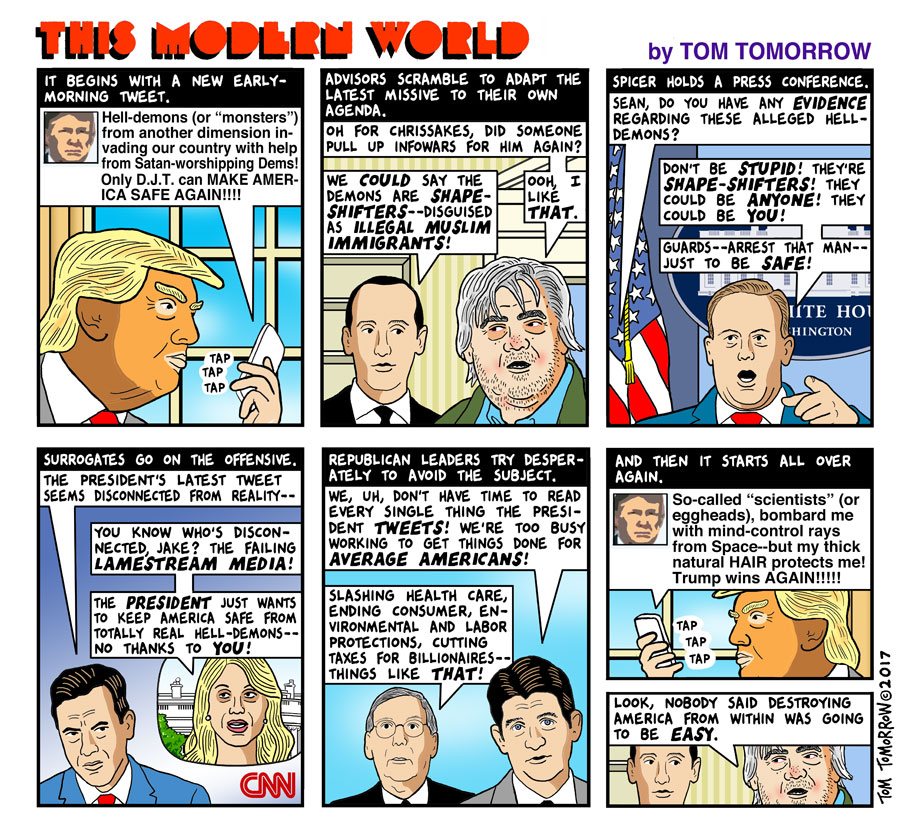

Cartoonist Dan Perkins increasingly turns to the iconography of science fiction to keep pace with the absurdity of the moment.

Dan Perkins was born in Wichita, Kan., in 1961, back in the days when the future still existed. The Kennedy presidency and the New Frontier gave birth to the last plausible and widely shared utopian moment, one that outlived John Kennedy’s own assassination by a few years but ultimately withered in the face of increasing pessimism. It was the Apollo epoch, the time of the space race, of American engineering and technocratic mastery, of scientists in crew cuts who promised health and happiness via gizmos and pills, of slick and streamlined advertising and pulp art merging with high culture in the works of Roy Lichtenstein and Andy Warhol, and of science fiction dreams entering the public imagination via Star Trek. In that giddy moment, even so misanthropic an artist as Stanley Kubrick could dream, as he did in 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), of humanity making an alien-assisted evolutionary leap into the stars.

But the shiny, gleaming utopia promised by that moment never arrived. Instead, dystopian anxieties came to the fore: the environmental nightmares that became mainstream in the 1970s, the dreary corporate-controlled future envisioned by cyberpunk in the 1980s, the increasingly frightening futures predicted by climate scientists and cli-fi writers trying to imagine how humanity will wrestle with a warming planet.

Like most good artists, Perkins, who cartoons under the pen name Tom Tomorrow, has never completely let go of his childhood and continues to be nurtured by the wellspring of creativity that comes with our first awareness of the world. He’s never lost a taste for the iconography of Cold War science fiction: bug-eyed aliens who fly around in UFOs that resemble kitchenware, wild-haired mad scientists, metallic robots, and city-crushing monsters. It’s hardly an accident that Perkins has a full-arm tattoo of the poster for Forbidden Planet, the much-loved 1956 science fiction reworking of The Tempest that featured Robby the Robot.

Although the political cartoons he’s been doing weekly for three decades are topical, they also contain in their iconography a hidden argument that goes beyond partisan politics: Repeatedly his cartoons have used the images of a promised future that never arrived to accentuate the failures of the disappointing present.

No comments:

Post a Comment