". . .A useful analogy in thinking of the social history of opium is that of an opportunistic pathogen, one that goes through long periods of dormancy, affecting very small numbers of people. But when social processes and historical events provide the pathogen with an opportunity, it bursts out to rapidly expand its circulation. With opium this happened in several phases, over centuries, usually in connection with empires. The Mongol Empire, for instance, along with its successor states, played an important role in propagating opium in many parts of Asia in the 15th and 16th centuries. This came about because opium was adopted as a recreational drug by imperial courts and ruling elites; it was not used as an instrument of state policy. The pioneer in that regard was the Dutch East India Company, which made extensive use of opium in its quest for commercial and territorial expansion in Southeast Asia. Yet while the Dutch led the way in enmeshing opium with European colonialism, it was the British in India who perfected the model of the colonial narco-state, when they began to use opium to pay for their imports of Chinese tea, a commodity that produced enormous revenues for Britain in the colonies as well as the metropolis.

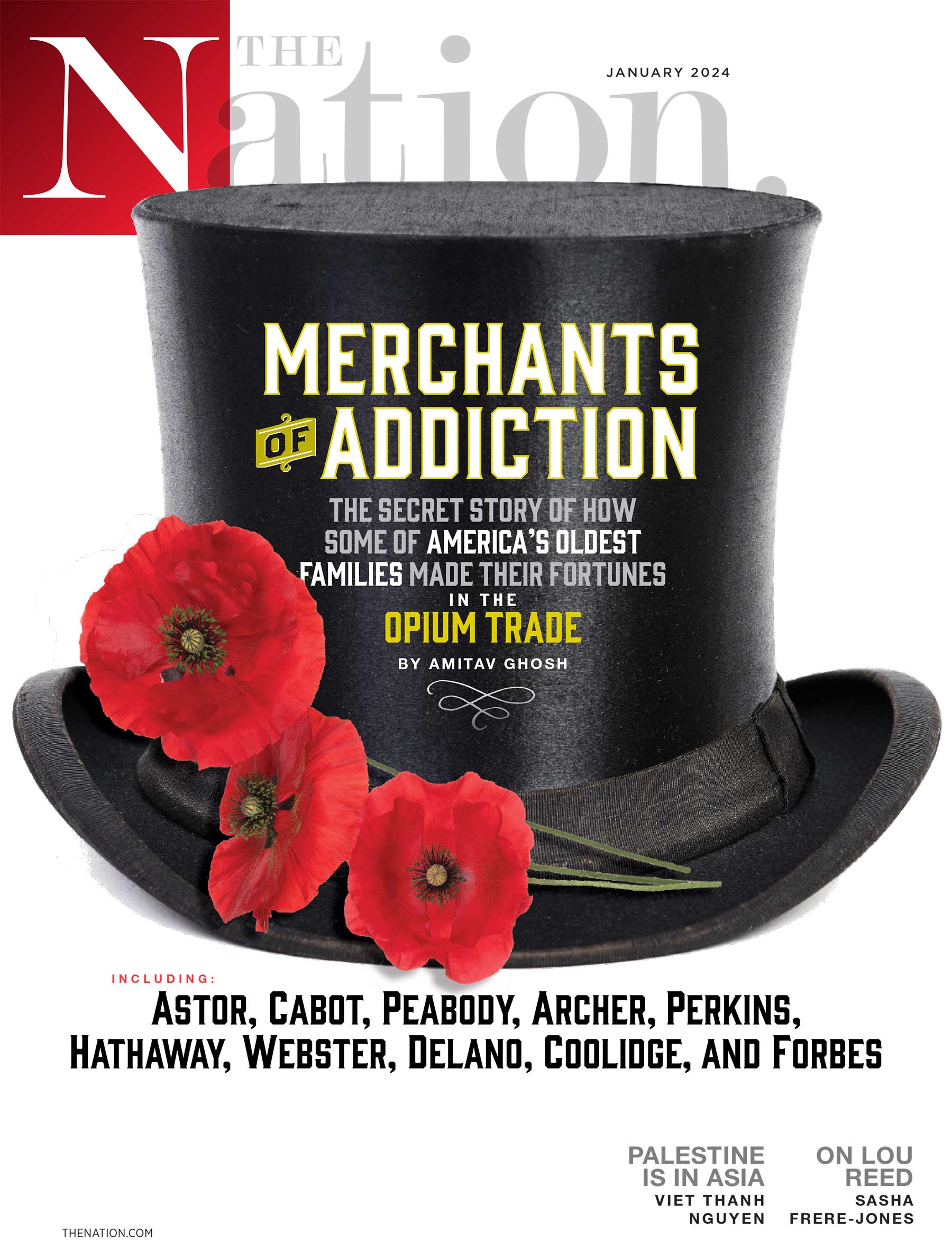

After Britain, the country that benefited the most from the China trade—and, therefore, the global traffic in opium—was none other than the United States. And in the United States, unlike in Britain, it is well-established that the beneficiaries included many of the preeminent families, institutions, and individuals in the land. . .

Many of the Yankees who established the American connection with China were, similarly, from the more penurious branches of the families of rich merchants. Usually they were the nephews of wealthy or influential men, and their entry into the business came about through nepotism, in the exact sense. This was true, for instance, of Samuel Russell, the founder of Russell & Co.: He started off in Middletown, Conn., as a “half-orphaned” white boy with only an “ordinary schooling.” But he had uncles in Providence who did business with China, and it was they who initially sent him out to Guangzhou and helped him establish his company. He could not have built his fortune without his family connections. That he was believed to be a “self-made man” is a sign of how the expression often conceals many kinds of privilege.

To go out to China at this time meant being away from one’s home for years on end, so young men needed to be very hungry and highly motivated to make the journey. It is not surprising, then, that many of those who went were the poor relations of rich men, boys who had grown up in the orbit of wealth, chafing at their own straitened circumstances and longing for an opportunity to better their lot. But to be merely intelligent, ambitious, and white wasn’t enough: A certain kind of class privilege was essential. To succeed in Guangzhou, a young American needed an education, as well as family connections to secure for him not just a clerkship in a good firm but also access to capital, which usually came, as in Will Irving’s case, from relatives. A penniless white boy from the backwoods, no matter how intelligent, hardworking, or ambitious, would have stood very little chance of finding a place at Russell & Co., let alone a Jew or a Black man.

Youth was another attribute that many American China merchants had in common, and sometimes it worked to their advantage, as it did for John Perkins Cushing, an impoverished nephew of Thomas Handasyd Perkins, one of Boston’s wealthiest merchants.

___________________________________________________________________________________

No comments:

Post a Comment