The Gila River People, Victims of Modernity

The river people

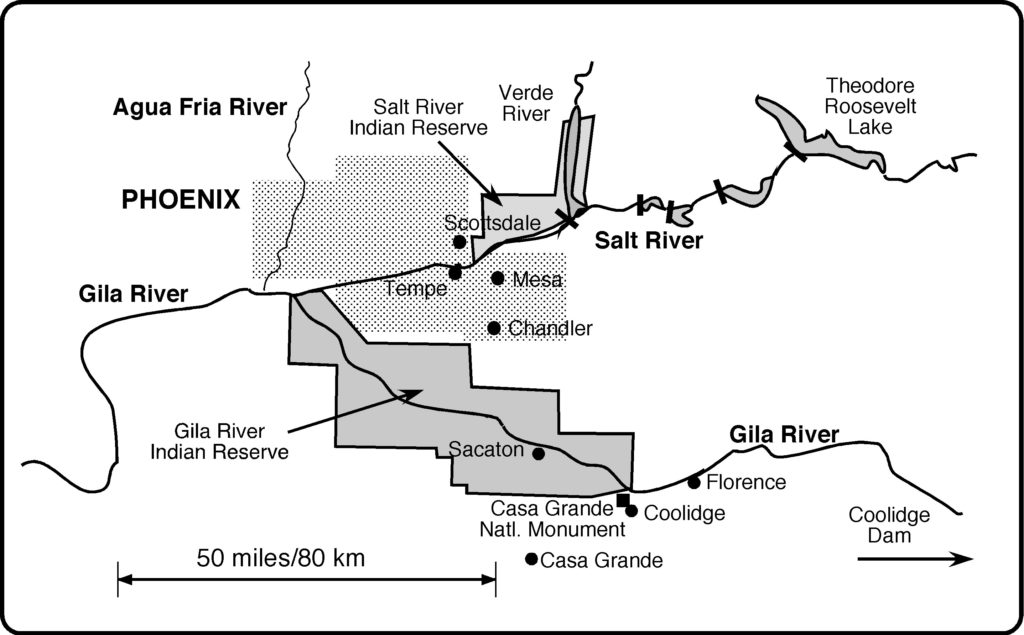

“Centuries ago the Hohokam Indians lived in the fertile valleys of the Salt and Gila rivers.” So begins a collection of the legends of the Pima Indians written by Anna Moore Shaw (3). Shaw was herself a Pima Indian, or, as they called themselves in earlier times, the Akimel O’odham, the River People. The Pima Indians of today live in an area south of Phoenix, Arizona, along the Gila River (Figure 2). Their location overlies what we know about the Hohokam lands.

Figure 2. The home of the Gila River Indian Community The Salt and Gila Rivers flow east to west. Present day dams that divert the Salt River into a series of canals are indicated. Roosevelt Dam was completed in 1911, creating Theodore Roosevelt Lake, and Coolidge Dam was completed in 1930. Important locations include the Casa Grande structure, an artifact of the Hohokam times, and the city of Florence, site of the Florence Canal, which is described in the text. The Gila Indians today live on the Reserve shown, with headquarters at Sacaton. The related Salt River Pima-Maricopa Indians live on a separate reserve on the Salt. . .

A tale of two countries

The Pima Indians living along the Gila River in Arizona are closely related to another Pima group who live in the northwestern Mexican state of Sonora, in the Sierra Madre Mountains (Figure 6). They belong to the same linguistic group, and share almost all of their genetic identity (5). But their medical conditions are very different, and starkly illustrate the importance of living conditions and circumstances on health.

What became an existential threat was the taking of the water, a threat that was almost inevitable . . . once Americans began to settle the land east of the Pimas. Those farmers needed water, and they took it. A series of diversion dams was built on the Salt River (Figure 2) and on the upstream Gila River. As early as 1859, an American Indian agent warned that diversion of the water would cause irreparable damage to the Pima people, and their community would become uninhabitable. This was in response to an investigation by the Department of the Interior to a proposal from The Florence Canal Company to build a waterway to irrigate the farms of white settlers, in 1886 (the city of Florence is indicated on the map). Nevertheless, the diversion dam and canals were built. In the words of Russell, “A thrifty, industrious, and peaceful people that had been in effect a friendly nation rendering succor and assistance to emigrants and troops for many years when they sorely needed it was deprived of the rights inhering from centuries of residence. The marvel is that the starvation, despair, and dissipation that resulted did not overwhelm the tribe.”

Despite a promise by the Florence Canal Company to not diminish the water supply to the Pima, that is exactly what happened. By 1880 the Gila was insufficient to sustain the Pima agricultural economy, and domestic water was lacking for many. The Pima, reluctant to give up, dug wells for water to maintain their livestock, but even this was stymied as the water table began to fall due to wells on the many farms upstream. The Pima became woodcutters, harvesting mesquite and selling it, until it was gone. The historian DeJong has concluded, “Handicapped by federal land and resource policies, the once-prosperous Pima descended into poverty. . . Convenient scholarly assumptions that American Indians were inherently unfit for, or overwhelmed by, unfamiliar western economies, however, are specious. In the case of the Pima, it was not a matter of the triumph of western civilization that displaced their economy as much as it was federal and territorial laws that prevented them from building on their economic success.” (4)

No comments:

Post a Comment